子路曰、衛君待子而為政、子將奚先。子曰、必也、正名乎。子路曰、有是哉、子之迂也、奚其正。子曰、野哉、由也、君子於其所不知、蓋闕如也。名不正、則言不順、言不順、則事不成。事不成、則禮樂不興、禮樂不興、則刑罰不中、刑罰不中、則民無所措手足。故君子名之必可言也、言之必可行也、君子於其言、無所茍而已矣。

Zi-lu said, “The ruler of Wei has been waiting for you to help him administer the government. What will you consider the first thing to be done?”

Confucius replied, “What is necessary is to rectify names.”

“So, indeed!” said Zi-lu. “You are wide off the mark! Why must there be such rectification?”

Confucius said, “How uncultivated you are, Yu! A superior man, in regard to what he does not know, shows a cautious reserve. If names be not correct, language is not in accordance with the truth of things. If language be not in accordance with the truth of things, affairs cannot be carried on to success. When affairs cannot be carried on to success, proprieties and music will not flourish. When proprieties and music do not flourish, punishments will not be properly awarded. When punishments are not properly awarded, the people do not know how to move hand or foot. Therefore a superior man considers it necessary that the names he uses may be spoken appropriately, and also that what he speaks may be carried out appropriately. What the superior man requires, is just that in his words there may be nothing incorrect.”

— Analects, Book XIII, Chapter 3

As Confucius taught, the rectification of names is the beginning of wisdom. What this means is that in order to effect change, one must have an understanding of the true nature of things; an understanding of the true nature of things comes from using the correct names for things. For example, you are a serf.

Now, at this point, I imagine that you have straightened your shoulders, puffed out your chest and said something to the effect of “Nonsense! I am a sovereign citizen of this republic and a free man. I own me.” If this were true, then why is it required of you to notify your lord’s magistrates when traveling outside the boundaries of his manor? And if you are granted permission to travel outside of your lord’s manor and desire to return with a buxom peasant wench to wife, while we live in such enlightened times that our masters no longer exercise droit de jambage, you still must petition your lord for the privilege of cohabitation within your cottage.

Pravo gospodina by Vasiliy Polenov, 1874.

Why do you take umbrage at the employment of such terminology? Does it not adequately describe the state of affairs (de facto)? I suspect that some of you reading this are now protesting “we just can’t have serfs traveling between manors without oversight! How do we know that some don’t mean us harm?” Well, isn’t the entire point of the feudal contract that the serfs work their liege-lord’s land in exchange for his protection from all threats?

Ok, ok! I see that my rectification of names has rankled. The present example hits too close to current fears and anxieties, and this perhaps obscures the point. So let’s turn to another feudal duty, tallage. Imagine that your lord has levied tallage upon your cottage and has sent you a notice for payment. Regardless of how well or not you have rectified names, you are aware of the consequences of not paying the tallage. First, the lord’s magistrates will send more notices for payment, and with each notice the tallage will be higher. If you still refuse to pay the tallage, the shire reeve (i.e., sheriff) will visit your cottage to demand payment. The shire reeve and his men have been deputized by their lord to take you away from your cottage and seize your property if you still refuse to pay the tallage. If you display even a modicum of resistance, the shire reeve is entitled to use as much force as necessary, up to and including deadly force, to subdue you.

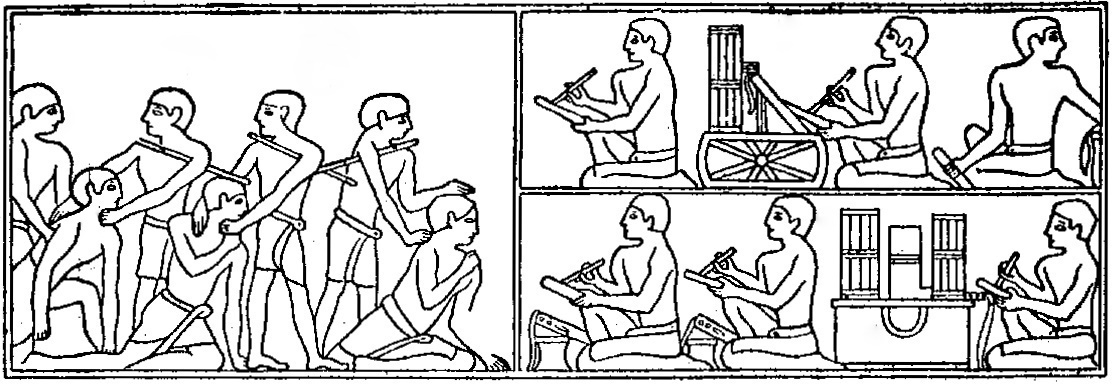

Egyptian peasants seized for non-payment of taxes (Wells, 1920).

Now, you might not see anything wrong with this situation. After all, as a serf, you are well-fed and well-taken care of. All that I ask is that things are called by their true names.

All that I ask is that things are called by their true names.

You can ask all you like, I’m still calling you HM.

When pronounced correctly, my true name sounds like this.

When pronounced correctly, my true name sounds like this.

This is how your name is pronounced in Slav-landia.

that is so disturbing I am sending it to my wife

This serf very much enjoyed your article HM. I also appreciate the shire reeve information. I enjoy etymology and I look forward to more.

That said, trying to draw parallels between a feudal lord and his manor, and the gigantic federal bureaucracy ruling the United States is a stretch. I understand the sentiment, I just don’t think the facts make for a valid comparison.

It’s not necessarily that the machinery of both are similar, but that the end products of such machinery are.

It’s worth noting, however, that at least under open feudalism allodial title existed. (Allodium being Medieval Latin for “land held in full,” that is, not under the control of a higher landlord) The 5th Amendment made allodial title non-existent as the Federal government was seen as the ultimate landlord for all lands within the country, which was a battle Thomas Jefferson lost as early as 1774 (Start reading at the 3rd paragraph from the bottom).

Holy fuckerballs.

This could easily be a blog post from 2017.

Makes me wish I was a history or civics teacher.

You delightful man, how droll.

Still reading, but this is fantastic. Just had to interject.

Finished. It’s delightful, in a cynical and yet nerdy fondness for etymology sort of way. It’s tickling me that a reeve was traditionally a post for a thieving shithead; master of his Laird’s purse and affairs. I’d never before this made the connection to “sheriff”. Interesting, innit, how the post went from being manager of purse to “protector of all that is good and lawful”. Social engineering, what can’t it accomplish. I mean, besides order and justice, obvs.

Very well done, you. And remarkably apt. Sadly, unfortunately, remarkably apt. Sharing this one far and wide.

Thank you.

*tips fedora in your direction*

Having studied stratigraphy, archeologists know that civilizations are built upon the collected sediment of previous cultures. This is true when talking about artifacts as well as semiotics.

*something clever about middens*

They great thing about contemporary societies, we create ready-made middens. You could drill down into the trash heap that is the Kardashians and their empire, and I bet you find many interesting facets of Americana.

Pravo gospodina – Право господина

Means, literally, “Right of the Lord (or ruler)”. Interestingly enough, in Russian speaking areas in UKR, and Russia herself, the titles, “gospodin” and “gospozha” («господин» «госпожа») “Mr.” and “Mrs.” are making a comeback, as for the longest time after the Commies took over, the idea of formal titles of any type (including professional ones, like “Dr.” or “Professor”) were generally eschewed.

When I first arrived here, I was referred to by my given name sans title, and only in the last few years has “Dr. Maximus” become more accepted.

I had the opposite problem. Thai has a dizzying array of personal pronouns (Just a small sample here) of which the usage depends on various factors such as relative difference in age, social status, occupation, perceived intimacy, real or affected kinship, and politeness. At work, I was usually referred to as อาจารย์ (ahjarn ‘Prof.’). When someone used a different pronoun, I had to suss out, on a case-by-case basis whether this was a sign of a more causal and friendly relationship or an intentional slight.

Wow! That is *definitely* a recipe for a faux pas should one be culturally ignorant of language and local colour, modified by interpersonal circumstance. Seems cumbersome to me, though I also understand the need for such discrete specificity.

I also forgot to mention, when the Commies took over, certain titles were still in full effect, and…. do you have your *Shocked Face* ready? Why, political titles, of course!

Yep, they loved them some political titles, such as, “Sekretar,” («Секретар»), whilst ousting the tsar, an outlawed political title and franchise, in exchange for another one.

My pet theory is that, post-Enlightenment, we rejected the divine mandate of kings and have spent the ensuing centuries figuring out who, in absence of kings, does have the divine mandate to rule.

we…have spent the ensuing centuries figuring out who…does have the divine mandate to rule

“King” is a transitory term for, “leader,” someone either by fiat ad baculum (the most common – look at gangs, mafias, and even incorporated, Oligarchal, businesses to a great degree) , or incredibly gifted with a natural, intangible ability to persuade, and the rest will follow.

We are, primarily, pack animals, deriving safety, identity, and security, through sheer numbers, and while human beings can, have, and continue to achieve remarkable feats of labour while in independent solitude, those individuals are exceptions to the rule, since Division of Labour is vital to thriving industry. Which, I do think, from a certain POV, our erstwhile Obumbles was trying to convey, but since he is so hostile to Free Markets, the linguistics and meaning are totally alien to him, and it came out the awful and clumsy way that it did.

It was my impression that there’s a subtle social formality about gospodin/gospozha that we don’t see in English as currently used, in the same way someone might say “Why, thank you Mr. Maximus” if you held the door open for them.

I have consulted the yarrow stalk oracle on this new endeavor. Chung Fu transforming to Pi. Chung Fu indicates that by through openness Glibertarians might influence many and enlighten even the ignorant. Pi points to the drawing together of many people either around the subject or the subject with a larger group.

You managed to not use the Phrase of the Week, “deep state,” to describe the mechanism. Gold star and tenure wishes to you for resisting that glib (in a bad way) and overly-facile cliché.

I have been anxious for an HM post. HM does not disappoint.

This is why I appreciated that my law school still had one professor who actually read common law decisions in the original Latin. Words have to mean things or laws have no meaning. I was always disappointed that this argument seemed lost on many of my classmates.