Canada has, in the entirety of its history, gone through dramatic changes that have completely shifted its cultural and social perspective. No long standing Constitutional ideal defines Canada, its history and institutions have largely been driven by necessity, whether good or bad. Since American perceptions of Canada tend to range from this to this, these columns will be a general, not-too-serious layman’s overview of Canadian history as a whole for an American audience, touching on key elements that became grounded long-term influences on Canadian society and culture.

Norse Colonization (985 to 1014)

Because the Norse never really stuck around long enough to have any kind of influence on Canadian society, this is going to be the cliffnotes version:

According to the Icelandic Vinland Sagas, in 985 AD a guy called Bjarni Herjólfsson is blown off course and sees land to the west, which he calls Vinland (he also may have picked up two shipwrecked guys, the sagas have multiple versions). He goes to Greenland and tells a guy called Leif Erikson about it, who buys his boat and sails there to set up a winter settlement (likely on the northern tip of Labrador). After exploring a bit he goes home. Four years later, his brother Thorvald shows up at his winter settlement and decides to pick a fight with some sleeping natives, starting the first European-Indian conflict. He gets shot by an arrow and dies. Everyone else leaves.

Six years after that, a guy called Thorfinn Karlsefni, who knows about Leif’s voyage, tries to set up a permanent settlement. It does not go well. They run out of food the first winter and decide to eat a beached dead whale, causing mass illness. They also argue about who is more awesome, Thor or Jesus. Unlike Thorvald, Thorfinn is smart enough not to attack the natives, and tries to negotiate a trade deal. But then a bull shows up and scares the natives away. A few weeks later they come back and attack. The Norsemen flee when the natives throw a whistling, inflated moose bladder on a stick at them (I’m serious). Freydís, Thorfinn’s pregnant half-sister, thinks the men are being cowards, so she picks up a sword, pulls down her top and slaps her breast with it. Somehow this scares away the natives, so European steel and tits save the day. Everyone is tired of dealing with shit like this, and they go home. The only substantial contribution Thorfinn’s expedition provides is that his son Snorri is the first European born in the New World.

All of this is based on the accounts of the Sagas, which tend to have multiple versions of the same events. There are tons of arguments amongst historians about the true extent of Norse expansion into North America and even where Vinland actually is. Some say it’s Labrador (making the Norse the first and only people to ever think Newfoundland is a paradise) while others say they expanded further into the Gulf of St. Lawrence region. Archaeological evidence is primarily based around the site at L’Anse aux Meadows, which some people argue is Erikson’s winter settlement. Recently in 2015 a new site at Point Rosee was discovered, but they’re still not entirely sure if it was a permanent settlement or a mining camp. Other more debatable evidence includes the Maine Penny, an 11th century Norse coin found in Maine.

Regardless, the early Norse voyages did not leave any impact on Canadian society, and once the Medieval Warm Period ended and the Greenland colonies could no longer support themselves, the Norse’s ability to sail west was severely curtailed.

Proper European Exploration (1497 to 1534)

With the discovery of the New World by Columbus in 1492, suddenly everyone wanted to get expeditions going to see if they could find the passage to India and China that he had missed. In 1497 the English Crown funds a guy called John Cabot’s expedition to the North Atlantic. Well, his name isn’t really John Cabot, like most explorers of the period he’s actually a filthy Italian named Giovanni Caboto, but the English, like everyone else, don’t want to advertise that they’re outsourcing their work to filthy Italians. Cabot’s four journeys in the North Atlantic are actually haphazardly recorded, but we do know that he discovered land somewhere around modern day Labrador, and also found the Grand Banks fisheries.

The banks contained so much cod that when they were actually utilized by European fishermen later on the price in Europe dropped dramatically. The discovery of the fisheries ensured that Europeans would continue to be interested in the region and explore it further. Cabot’s later journeys primarily focused on trying to find the Northwest Passage, the shipping lane that would allow trade with the Far East. The search for which will lead to many expeditions, some beneficial, others massive disasters, none of them successful. Cue the Stan Rogers.

For most of the early 16th century the only people really exploring around the general location of Eastern Canada are the Portuguese. Portuguese fishermen utilize the Grand Banks and set up a few minor seasonal fishing outposts on Labrador. Unfortunately for them, under the Treaty of Tordesillas, it’s technically Spanish land, so they abandon it to focus on the more prosperous colonies in South America. With Spanish and Portuguese interests primarily in the south, Canada is open for whoever is willing to take it.

Enter the French (1534 to 1604)

It’s 1534, and France has been making a good comeback lately. After victory in the Hundred Years War they have stabilized their country and established themselves as the military superpower of Europe, a tradition that will continue until the 19th century. With a great deal of wealth, a large army, language dominance in diplomacy and other fields, and massive population in comparison to everyone else, they were set to dominate the European continent for the next century.

And then the Spanish start shipping over tons and tons of gold from their newly conquered subjects in the New World. Suddenly continental dominance isn’t going to cut it anymore; they need to expand outside of Europe in order to stay competitive. In 1534 French King Francis I tasks a man named Jacques Cartier (who is, surprisingly, not a filthy Italian) to find that wonderful Northwest Passage and, you know, if he happens to conquer any extremely rich savages along the way, they’re fine with that too.

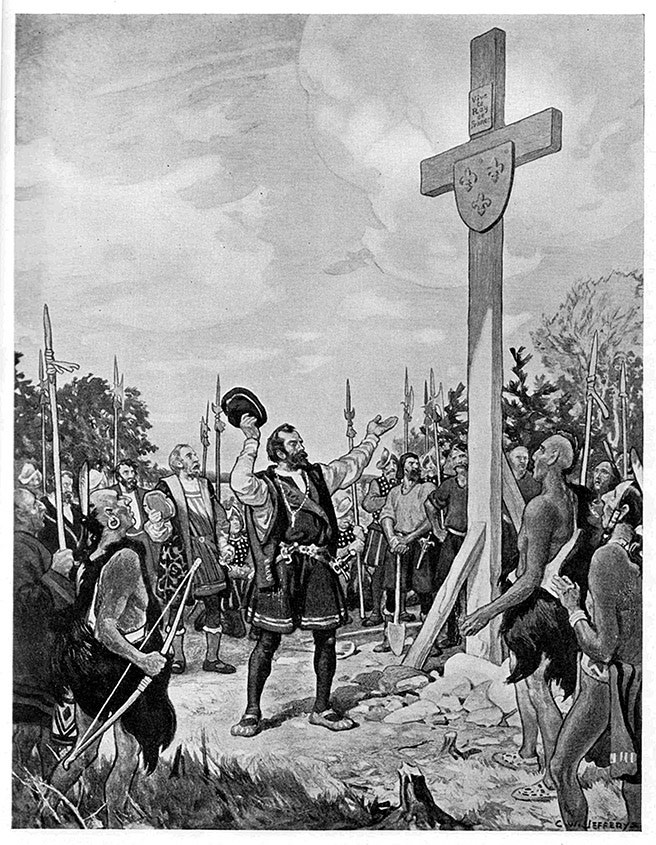

Cartier sails into the Gulf of St. Lawrence (possibly dooming a species to extinction along the way) and goes on a general tour of what would become the Maritime provinces. He establishes contact with the local aboriginal groups, likely the Mikmaq and other tribes, who are willing to trade. On the Gaspé Peninsula he plants a cross, formally claiming the land for the kingdom of France. The local natives do not appreciate this, and then he tries to kidnap a chief’s sons, but ends up negotiating to take them back to France. The entire time he thinks he’s actually somewhere in Asia.

Cartier’s second voyage back was more eventful. This time, he travels down the St. Lawrence River, what would become the primary shipping lane for the later Canadian interior. Cartier is convinced that this is the Northwest Passage…little does he know where it ends. He’s brought the chief’s sons back with him, and they take him to the capital of their native nation, Stadacona, a village near modern-day Quebec City. According to Cartier’s journals and this Heritage Moment, this is where the term ‘Canada’ is first used.

Cartier continues down the river, but is stopped at the rapids near the village of Hochelaga, on the island now known as ‘downtown Montreal’. They return to Stadacona in order to wait out the winter, but have completely failed to provision food and firewood. Cartier’s ships are frozen in place by a very harsh winter that they were not prepared for. Everyone starts to get scurvy, and to make things even more miserable, the local natives start catching European diseases and dying. The natives teach the French how to use spruce to cure scurvy, and the local chief tells Cartier about a kingdom rich with gold and jewels to the north.

So Cartier kidnaps him and brings him back to France, along with seven others (there’s a fairly consistent theme in Cartier’s voyages, can you guess what it is?). None of them ever make it back home and all but one die on the way back to France. The chief’s stories convinces Cartier that there is a great ‘Kingdom of Saguenay’ that would be ripe for the taking. By 1540 King Francis I decides that there should be an established, permanent settlement in the New World, and commissions Cartier to do it.

But within the French court, a new privateer has gained the king’s respect. By 1541 Francis has changed the plan, and now Cartier is second in command to a Huguenot, Jean-François de La Rocque de Roberval, who is named the first lieutenant general of French Canada. Roberval has spent most of his time recently dodging executions thanks to his influence over the king, so his reason for getting out of France is probably health related. They sail to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, where Roberval decides to wait for supplies and gives permission to Cartier to continue on down the river.

Cartier travels back down to Stadacona, where the natives are not happy to see him, for some reason. Regardless he sets up a colonial settlement nearby called Charlesbourg Royal. As they begin to try to set up fields for farming, the settlers (mostly convicts, by the way) begin to find what they think is diamonds and gold. Cartier is quite giddy, but still wants to go further down the river to see if he can find his mystical kingdom. The rapids stop him again, and he returns to the settlement to find hell breaking loose. The natives have attacked and killed a large number of settlers, and the situation seems desperate.

So Cartier fills his ship up with diamonds and gold and heads back out to the ocean. When Cartier’s about to meet up with Roberval, he has just abandoned his sister on a deserted island, likely for financial benefits back in France. Jacques Cartier, Master Dick of French Canada, won’t be out-dicked on his own territory, so under cover of darkness he sails past Roberval’s ships and returns to France without him. Somehow he fails to kidnap Roberval’s sister on the way by.

Almost no one in this story gets a happy ending. Cartier’s diamonds and gold turn out to be quartz and fool’s gold, and he never sails to the New World again. He dies in 1557 due to an epidemic. Roberval attempts to take over Charlesbourg, but abandons it in 1543 due to constant native attacks and lack of supply. He’s later assassinated during the start of the French Religious Wars. Roberval’s sister was rescued however, and became a bit of a minor celebrity once accounts of her story were published.

For the next fifty years, there will be few attempts to permanently colonize French Canada, and none of them will succeed. France is going through a period of instability. The logistics, geographical knowledge, finances and a willingness to not piss off the locals simply isn’t there. If only there was some man, a manly man of integrity and ability, of both diplomatic and martial skill, a mariner with a gift for administration, to get things going again.

Surely France won’t be able to produce one of those.

*Throws up PM Links right after John Titor’s post*

Sorry dude, no idea why everyone isn’t commenting.

I can always count on you Playa.

Eh?

I think this is at least a 50 Timbit worthy post!!!!

With the exchange rate that’s like forty-six cents American!

How many Canadian Tire dollars would you pay for it?

I’ll comment. Canadians are fucking weird and their country is fucked up. And to add insult to injury, the elected Zoolander. No wonder half the commenters here are from Canada, their fellow citizens drove them to madness.

You elected Obama.

We learned it from watching you!

Really cheap comeback, John, really really cheap. But true.

followed by an immediate post pm links article.

Rough ending for the lass.

The Norsemen flee when the natives throw a whistling, inflated moose bladder on a stick at them (I’m serious)

The old rotting internal organ bomb. Thanks for the info. You never know when such a thing may come in handy.

Great job, John. I hope you continue all the way and educate us all how Canada was the main reason why the Allies won World War I. That’s what I remember from a Canadian history book I read.

+1 Vimy Ridge?

Vimy Ridge was the blueprint for all future Allied successes. It is known.

I will steal Swissy’s *standing ovation*. You made me laugh AND a little less ignorant.

Lived in North Bay Ontario a while as a kid. Had a Canadian girlfriend for a while. Did some reading up on Canadian history a few years back.

Though I try, I still just cannot generate any level of curiosity. But thank you for the post.

I forgot to add, Sorry.

North Bay will do that to you.

15-odd years ago, I bought and sat through the entire DVD set of “Canada: A People’s History”. God help me, I thought it was interesting and informative.

I should try comparing each episode with a JT chapter and see the differences.

I bought and sat through the entire DVD set of “Canada: A People’s History”

Guess what they showed me in elementary school history class, old man.

Pfft, time travelers forgo the right to talk about age!

“Canada: A People’s History”

Was Howard Zinn a consultant or is it actual history?

It’s been a long time since I last saw it, but I remember most of the pre-20th century stuff being pretty good.

The later stuff tends to get a little masturbatory and TOP MAN.

Thanks!

Like always, Canadians saw something US was doing, adopted it and then made it bland and pointless (e.g. Obama vs Zoolander).

For the most part it’s OK provided you accept that French were bad to natives, but not as bad as British were to French, which pales in comparison to barbarity of Americans and their treasonous revolt, which was mostly done so they could genocide the natives.

Also, Liberals are the true ruling party, and Tommy Douglas is the greatest for giving us health care.

So overall, as I remember it, history with a spin.

Thanks!

Tommy Douglas is the greatest for giving us health care.

Canada’s version of “Without government, who would build roads?”

This made me think of Montreal’s reputation as a ‘restaurant mecca’. Yeh, we have great eateries but I wondered how bad were other cities for Montreal to get such a reputation. Years ago I went to a ‘restaurant owners convention’ with a guy who owned restaurants. There I learned all we did was copy ideas from NYC. I don’t know if that’s changed but I think that pretty much aligns with what you wrote. We do have great restaurants but no sure it’s a mecca since we’re not trailblazers as far as we know; and our cafes our over rated. I was more impressed by the choices I saw in Chicago than what I see here; and I’m an espresso aficionado of sorts.

Also, Tommy Douglas is not dead enough.

Great article.

For the next fifty years, there will be few attempts to permanently colonize French Canada, and none of them will succeed. France is going through a period of instability. The logistics, geographical knowledge, finances and a willingness to not piss off the locals simply isn’t there. If only there was some man, a manly man of integrity and ability, of both diplomatic and martial skill, a mariner with a gift for administration, to get things going again.

Surely France won’t be able to produce one of those.

I see the next part coming.

Funny story about American misconceptions of Canada: A former coworker of mine thought Canada was made up of five provinces and two territories. I think this took place before Nunavat split off from the Northwest Territories. I can’t remember his list. I think it was that the provinces were “Nova Scotia, Montreal, Toronto, Ontario, British Columbia” and the territories were “Yukon and the Northwest Territories”. I tried correcting him. He didn’t believe me. The next day I brought an atlas with me to work and showed him.

Very nice first post, Titor! I look forward to moar.

Nice post, John. Looking forward to the rest. I am embarrassed to admit I have not looked into Canadian history since high school, and having not lived in Canada before then I had little knowledge of it beforehand.

Great stuff JT. Wouldn’t expect anything less. It gave me an orgasm.

Those filthy I-talians, having all the hoarded cash, funded early exploration behind the scenes including those of the Porks and Spics.

I laughed, I learned, I even got a semi when you talked about that broad pulling her top down. Good stuff.

I did a paper once about the U.S. fugitive slaves who made it to Canada. While they weren’t universally welcomed, their presence was kind of a FU to the Yanks. Then most of them came back to the U.S. to fight the Confederacy and/or move back there.

Interesting. Didn’t knew about Cartier’s fondness for kidnapping. I was taught that the natives he took back with him were volunteers. Then again, all my history teachers were french separatists so….

I was told Basque fishermen were actively fishing in the Maritimes way before Columbus “discovered” America. They even traded with the natives. Everyone knew where the place was, they just didn’t care nor bothered to establish permanent settlements. With the constant wars and the black plagues, they had plenty of space in the old continent.

Canada has a complex and interesting history, with strong western values. It’s a shame that the liberals are actively trying to flush all of that down the drain and that the younger generation think all we’re good at is deploying some blue helmets.

*cue in the O Canada! old tv sign animation from CBC

Yes, Quebec’s nationalist version of history is, erm, a little different.

The arguments in regards to pre-Columbus Basque fishermen, along with the Portuguese, St. Brendan, that Malian guy and the Chinese discovering Cape Breton are avoided specifically because they lack supporting archaeological evidence.

From what I’ve gathered it was more a case of ‘Cartier wouldn’t let them say no’. If he could negotiate, he would.

Seriously though, John. Great stuff. You got jacked on the time slot.