Charles Jones and C. A. Cecil were Jehovah’s Witnesses from Mount Lookout, West Virginia. On June 28, 1940, they came to the nearby town of Richwood. Richwood’s dominant local industries relied on harvesting the high-quality (or “rich”) wood from local forests. Jobs working wood and coal helped swell Richwood to about 4,000 inhabitants. That represented a lot of doorbells to ring and souls to save. Simultaneously with spreading their spiritual message, Jones and Cecil wanted to get signatures on a petition against the Ohio State Fair, which had cancelled its contract to host a national convention of Witnesses.

Under the dictatorial direction of their boozy but efficient leader, Joseph Franklin Rutherford, the Jehovah’s Witnesses had become a society of evangelizers. All members were required to spend time spreading Christian truth to their neighbors (in time which they spared from their day jobs). Basically, as many people as possible needed to be rescued from the diabolical world system, dominated by evil governments and the “racketeering” clergy of other religious groups. The end times were imminent, or had already arrived – the exact details changed with time, but the urgency of the situation did not change. Witnesses had to descend on communities like “locusts” – Rutherford’s term – and turn people to God’s ways.

The true nature of the current wicked system must be made clear in publications, speeches, and even phonograph records. Certain sinful behavior must be shunned. In 1935, Rutherford had made clear that saluting the U. S. flag was idolatry – Rutherford compared it to the Nazi salute. (To be fair, until the end of 1942, the American flag salute was uncomfortably similar to the Nazi salute – and German Witnesses were killed or put in concentration camps for their defiance.) Young Witness men must not sign up for the draft because all Witnesses – not just the leaders – were ministers and entitled to the draft law’s exemption for clergy.

In World War I, before Rutherford took over, the antiwar teachings of the Witnesses (then called Bible Students) had been so provocative that it was persecuted in many countries including the U.S. And as a new world war was underway, Rutherford had ratcheted up the confrontation between his group and the forces of mainstream American society. A new era of persecution was dawning as mainstream American fought back in often-ugly ways.

Jones and Cecil were picked up by the police, who took them to state police headquarters, where cops and members of the American Legion (a nationalistic veterans’ group, more militant at the time than it is today) interrogated them. Martin Louis (or Lewis) Catlette was a twofer, a Legionnaire and a deputy sheriff. This sort of overlap between American Legion vigilantes and law enforcement was common in the attacks on the Witnesses.

Catlette and others accused Jones and Cecil of being spies and Fifth Columnists and gave them four hours to get out of town. The two Witnesses returned to Mount Lookout, but came back to Richwood the next day, June 29, with seven more members of their sect.

Their enemies were waiting. The Legionnaires had searched the boarding house where Jones and Cecil had stayed, finding some very suspicious items, like maps (of homes the Witnesses intended to canvass), and literature about refusing to salute the flag or serve in the military. It was time to teach these subversives a lesson.

Catlette and his Legionnaire friends got the Witnesses together in the Mayor’s office, holding them prisoner there while Richwood Chief of Police Bert Stewart guarded the door. Catlette took off his badge, proclaiming that what he was going to do would be as a private citizen, not as a law officer.

A local doctor was among the Legionnaires, and he was not very mindful of the Hippocratic Oath. He brought some castor oil, which the mob forced the prisoners to drink.

Castor oil was then considered a useful medicine for intestinal distress if administered in small doses. If given in large doses, as in this case, it induces severe diarrhea. One of the Witnesses, who got an extra dose because he tried to resist, had bloody urine.

Forced dosing with castor oil had a notorious history. Mobs in Fascist Italy often poured castor oil down the throats of political opponents or people suspected of anti-social activities, as a humiliating lesson for anyone who dared resist fascism.

The Witnesses’ ordeal was not over. Catlette and his associates tied the Witnesses’ left arms together and paraded their prisoners through the streets and tried to force them to salute the U. S. flag (with their free arms). Then the vigilante mob marched the Witnesses to their cars, which had been vandalized, and ordered them out of town again.

Incidents like this were erupting throughout the country. The Germans had just overrun France and the Low Countries, and the public was on high alert for “Fifth Columnists” – Nazi agents undermining morale in preparation for an invasion. The Witnesses aroused suspicion because of their aggressive proselytizing, their vehement denunciation of the government (and every other religion but their own), and their refusal to salute the flag. The U. S. Supreme Court had just issued an opinion that public schools could force Jehovah’s Witness pupils to salute the flag (an opinion the Court would overturn three years later, saying compulsory flag-salutes violated the Witnesses’ freedom of religion). As in many countries, both Allied and Axis, the Witnesses were considered as a subversive influence and persecuted as such.

Attorney General Francis Biddle, in 1941, publicly denounced the “cruel persecution” of the Witnesses, but his Justice Department didn’t seem to be acting against the persecutors. Indeed, the feds didn’t mind doing some persecuting of its own, prosecuting Witnesses for resisting the draft.

(And after Pearl Harbor, there was the persecution of Japanese-Americans, as well as of the prosecution of certain critics of the war – but we’re getting away from the subject, which is how concerned the U. S. Justice Department was about the rights of minorities.)

In West Virginia, the local federal prosecutor, Lemuel Via, recommended against bringing charges in the Richwood case. The recently-formed Civil Rights Section of the Justice Department pressed for prosecution. By 1942, the Civil Rights Section had won out, and Via was instructed to take the case to the grand jury. Via asked the Justice Department to send one of its lawyers to assist him. This would show “that this case was being prosecuted by the Department of Justice, rather than the United States Attorney.” In other words, Via wanted to signal to the community that if it were up to him, he wouldn’t be harassing the local patriots simply for giving the Witnesses what they deserved.

So the Justice Department sent one of its recent hires, Raoul Berger, to help Via out and take the responsibility off of him.

Cue the scene-shifting special effects.

Raoul Berger was born in 1901 in a town near Odessa, now in Ukraine but then in the Tsarist Russian Empire. The Berger family was Jewish, and there was lots of anti-Semitic agitation in the empire. Also, according to Raoul’s later recollection, his father Jesse predicted (correctly) an impending war between Russia and Japan.

So it was time to emigrate. Jesse came to the United States in 1904, initially, perhaps, without his family. In 1905, Russia experienced the predicted war with Japan, a revolution, and an anti-Jewish pogrom in Odessa.

This may have reinforced Jesse’s wish to bring his wife Anna, little Raoul, and his sister Esther, to the United States, which Jesse did no later than 1907 (if he had not done it already).

Jesse worked as a cigarmaker in the West Side of Chicago. He wanted his son to study engineering, but Raoul was taken with music. Raoul acquired a violin, learned some gypsy tunes, and began more formal musical studies under a private tutor. After he got out of high school, Raoul went to New York City to study at the Institute of Musical Art, now Julliard. His teacher was Franz Kneisel, a rigorous and stern instructor. Raoul later reflected on how, in studying the violin, he learned “patience and rigorous attention to detail,” which stood him in good stead throughout his life.

After an unsuccessful sojourn in Berlin to study under Carl Flesch, Berger came back to New York to finish his studies with Kneisel. Then it was on to Philadelphia to play violin for the Philadelphia Orchestra. The conductor was Leopold Stokowski, whom Berger recalled as vain and insufferable, albeit a genius.

Berger lasted a year under Stokowski, and then went to Cleveland to become second concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, under Artur Rodzinsky.

After two years at this job, Berger got a position in Cincinnati as associate concertmaster to the conductor Fritz Reiner. With three others in the orchestra, Berger formed the Cincinnati String Quartet. In Berger’s telling, Reiner was dictatorial without the compensating advantage of genius like Stokowski.

Around this time, Berger stopped being a professional musician and started looking around for another line of work. Berger’s son Carl, in a brief account of his father’s musical career, suggests that there may have been financial considerations: Berger’s new wife was the daughter of a big-shot doctor, and Berger may have wanted to give his bride a better lifestyle than a Depression-era violinist could afford. By Berger’s own account, the problem wasn’t money, but the dictatorial conductors he worked under, which led him to reconsider his musical career choice.

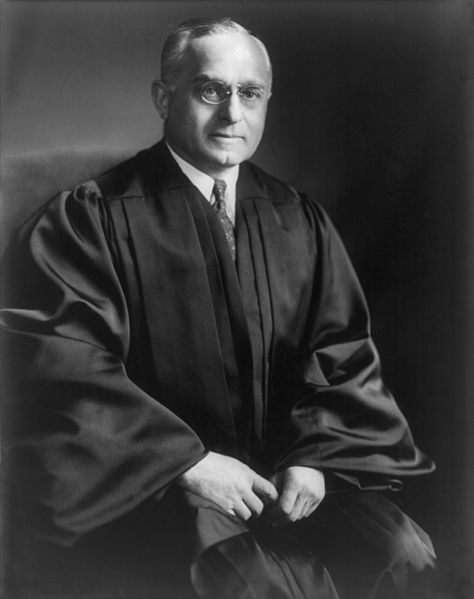

After the sight of a dissecting room scared him away from medicine, Berger went to law school at Northwestern and Harvard. At Harvard he was a student of Felix Frankfurter, who remained as a mentor figure after Berger’s graduation.

With excellent credentials, the new attorney tried to get a position in a big law firm, but none of them would hire him because he was Jewish. The firms he applied to had either filled their Jewish quota, or their quota was zero. Not even the intervention of Felix Frankfurter helped.

Fortunately, the head of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) was a friend of the dean at Northwestern, so Berger began working as a government attorney. The Department of Justice hired Berger away from the SEC, and now they dropped the Richwood castor-oil case in his lap. Berger later said, probably correctly, that his bosses didn’t like this case, and expected to lose, so they handed it off to Berger who was the “low man on the totem pole.”

Berger took the case to the grand jury. The Jehovah’s Witness victims testified about what happened to them. In a memorandum, Berger described how the grand jurors responded with hostile questions “about the particulars of their religion, their refusal to bear arms, their invasion of Richwood in search of ‘trouble.'” No indictments were forthcoming.

Since the grand jury refused to indict Catlette and Stewart, felony charges were not an option. Instead, the prosecutors filed an information charging Catlette and Stewart with the misdemeanor of denying the Witnesses’ civil rights “under color of law.” By seizing and mistreating the Witnesses, the charges said, the two lawmen had violated the Witnesses’ rights under the Fourteenth Amendment of the U. S. Constitution, including “the exercise of free speech”…

…and the right “to practice, observe and engage in the tenets of their religion.”

U. S. Supreme Court precedent at the time held that the First Amendment rights of free speech and free exercise of religion were also protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, and thus could not be violated by state officials. The Supreme Court had exempted the states from most of the Bill of Rights, but not from these key provisions.

U. S. Supreme Court precedent at the time held that the First Amendment rights of free speech and free exercise of religion were also protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, and thus could not be violated by state officials. The Supreme Court had exempted the states from most of the Bill of Rights, but not from these key provisions.

(The charges also said that the defendants’ behavior had violated due process and equal protection, which are specifically protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.)

The trial was held in early June 1942 in Charleston, WV. Federal District Judge Ben Moore presided. In his argument to the jury, as Berger later summarized it, “I played one string” – American boys were overseas fighting Mussolini, and these defendants were engaging in Mussolini-style behavior right here in the United States.

The jury gave its verdict: Both defendants were guilty.

Catlette was sentenced to a year in prison and a $1,000 fine. Stewart got away with a $250 fine, which he paid. Catlette appealed his conviction to the federal Fourth Circuit court. Berger helped argue the appeal on the government’s behalf.

While Berger was fighting to keep Catlette in prison, the University of Chicago Law Review published an article Berger had written in his private capacity. The U. S. Supreme Court had just given an opinion saying the public had a broad right to criticize judges, a right which neither the federal government nor the states could take away. In his article, Berger indicated that he was sympathetic to a broad vision of free speech, but – in an elaborate historical analysis – Berger argued that the historical meaning of the First Amendment allowed judges to punish their critics.

Speaking as a good New Deal liberal, Berger was glad that the Court was no longer imposing economic liberty on the country in the name of constitutional rights. These discredited conservative precedents (as he saw them) had led to “a generation of sweated labor and unchecked industrial piracy” from which the country was just recovering. But now that New Dealers controlled the Supreme Court, would they impose their left-wing activism on the constitution the way earlier courts had (allegedly) practiced right-wing activism? ” [I]t is easier to preach self-restraint to the opposition than to practice it oneself,” Berger reminded leftists.

What the Supreme Court ought to do, wrote Berger, was adhere strictly to the historical meaning of the Constitution, even if this sometimes produced results leftists disliked. Some advocates of judicial activism said judges should adapt the Constitution to modern circumstances. But “an ‘unadapted’ Constitution may be the last refuge of minorities if a national Huey Long comes to power.” (To Berger, it was Long, not FDR, who served as an example of a tyrannical populist demagogue.)

And in a foretaste of things to come, Berger included a brief footnote in his article noting the Supreme Court’s inconsistency on whether the First Amendment even applied to the states.

For now, though, Berger was seeking to apply the First Amendment to the states by locking up Martin Catlette.

In January 1943, the Fourth Circuit upheld Catlette’s conviction, rejecting Catlette’s claim that by removing his badge he had turned himself into a private citizen and was not acting “under color” of state law as the charges against him alleged.

The judges made short work of Catlette’s efforts to dodge responsibility:

We must condemn this insidious suggestion that an officer may thus lightly shuffle off his official role. To accept such a legalistic dualism would gut the constitutional safeguards and render law enforcement a shameful mockery.

We are here concerned only with protecting the rights of these victims, no matter how locally unpalatable the victims may be as a result of their seeming fanaticism. These rights include those of free speech, freedom of religion, immunity from illegal restraint, and equal protection, all of which are guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

The conviction of Catlette and Stewart represented the only successful prosecution in the country of anti-Witness vigilantism.

Catlette served his sentence in the Mill Point, WV, federal prison camp. As befitted someone who had only been convicted of a misdemeanor, Catlette did not live under a very harsh prison regime. Maureen F. Crockett, daughter of the prison’s parole officer, later wrote:

The minimum-security prison on top of Kennison Mountain had no locks or fences, and minimal supervision. Inmates stayed inside the white posts spaced every 40 feet around the perimeter. Escape was as easy as strolling into the nearby woods, but the staff took a head count every few hours. During the [twenty-one] years it was open, the prison had only 20 escapes.

Local lore says so few prisoners left because they thought the local woods were haunted.

For whatever reason, Catlette did not run off. He served eleven months of his twelve-month sentence before being paroled (and the court excused him from paying the fine). During his incarceration, he probably had the chance to meet some of the convicted draft resisters who were entering Mill Point at this time, including Jehovah’s Witnesses.

Berger continued his career as a government lawyer. His jobs included working at the Office of the Alien Property Custodian.

After his stint in government service, Berger went into private practice.

In 1958, Berger was devastated by the death of his wife. He considered what to do with the rest of his life. Perhaps, he thought, he could return to being a musician. He went to Vienna and gave a violin performance.

As Berger told it, he was deterred from resuming his musical career when he read a review in the Vienna press, saying that he played the violin very well…for a lawyer.

Berger began a new career as a law professor. Eventually, his research would lead him to the conclusion that the states did not have to obey the Bill of Rights.

How would Martin Catlette react if he knew that one of the prosecutors who sent him to prison for violating freedom of speech and religion would later claim the states were exempt from the Bill of Rights?

But before Berger got to that point, he had a date with destiny in the form of a crooked President.

Works Consulted

Cecil Adams, “Did Mussolini use castor oil as an instrument of torture?” A Straight Dope classic from Cecil’s store of human knowledge, April 22, 1994, http://www.straightdope.com/columns/read/965/did-mussolini-use-castor-oil-as-an-instrument-of-torture

Ancestry.com message boards > Surnames > Beck > “Not sure where to begin – Helen Theresa Beck,” https://www.ancestry.com/boards/thread.aspx?mv=flat&m=3755&p=surnames.beck

Raoul Berger, “Constructive Contempt: A Post-Mortem,” University of Chicago Law Review: Vol. 9 : Iss. 4 , Article 5 (1942).

Available at: http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclrev/vol9/iss4/5

_________, The Intellectual Portrait Series: Profiles in Liberty – Raoul Berger [2000], Online Library of Liberty, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/berger-the-intellectual-portrait-series-profiles-in-liberty-raoul-berger (audio recording)

Robert K. Carr, Federal Protection of Civil Rights: Quest for a Sword. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1947.

Maureen F. Crockett, “Mill Point Prison Camp,” https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1785

Bill Davidson, “Jehovah’s Traveling Salesmen,” Colliers, November 2, 1946, pp. 12 ff.

Robert Freeman, The Crisis of Classical Music in America: Lessons from a Life in the Education of Musicians. New York: Rowman and Littlefield, 2014.

“Italian Fascists and their coercive use of laxative as political weapons,” http://toilet-guru.com/castor-oil.php

James Penton, Apocalypse Delayed: The Story of Jehovah’s Witnesses (Third Edition). Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2015.

Shawn Francis Peters, Judging Jehovah’s Witnesses: Religious Persecution and the Dawn of the Rights Revolution. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

Richwood, West Virginia – History, http://richwoodwv.gov/history/

Chuck Smith, “Jehovah’s Witnesses and the Castor Oil Patriots: A West Virginia Contribution to Religious Liberty,” West Virginia History, Volume 57 (1998), pp. 95-110.

_________, “The Persecution of West Virginia’s Jehovah’s Witnesses and the expansion of legal protection for religious liberty,” Journal of Church and State 43 (Summer 2001).

Rick Steelhammer, “Whispers of Mill Point Prison,” Charleston Gazette-Mail, May 4, 2013, http://www.wvgazettemail.com/News/201305040074

“Mill Point Federal Prison and the Bigfoot,” Theresa’s Haunted History of the Tri-State, January 5, 2015, http://theresashauntedhistoryofthetri-state.blogspot.com/2015/01/mill-point-federal-prison-and-bigfoot.html

Note – There’s a Martin Lewis Catlette (1896-1965) buried in the Richwood Cemetery. I can’t say for sure if this is the same person as the deputy Sheriff (the appeals court gives the deputy’s middle name as “Louis”). The person in the cemetery seems to have served in the Navy in both world wars, and his wife died in 1943, the year that the deputy would have gotten out of prison. If this is the same person as the deputy, I would be able to add a paragraph about the widower, newly freed from prison, soothing his grief by returning to military service.

Violins are okay, but no sax.

especially before a fight.

Daddy dear

Let’s get outta here

I’m scared

10 o’clock

Nighttime in New York

It’s weird

I donut know about food puns, but I couldn’t finish the first helping of text.

I actually found this very interesting. Mr. Riven and I aren’t religious, but we do meet with this cute little JW girl a couple times a month-ish.

There are some interesting rumors about them. Like their places of worship often don’t have windows–so they must be sacrificing chickens, right?

“Mr. Riven and I aren’t religious, but we do meet with this cute little JW girl a couple times a month-ish.”

Go on…

Well, originally I only agreed because she really was just so darn cute, but honestly, it’s been really informative.

She’s getting married in a couple weeks. What a shame. We could’ve had so much fun…

*Frantically tries to cover SugarFree signal*

Too late. Take cover.

So, how did she square her religious beliefs with that? I guess that’s not something one can reasonably ask.

Sorry you lost your friend with benefits, but congratulations on having a situation like that in the first place.

Oh, we never got to the point where it was a “thing.” I was just hopeful that we might get her there. Maybe the next one 😛

Try finding a cute jewish girl. They tend to have less restrictive views on many matters.

I disagree.

Sample size n=1 Jewish wife.

Less restrictive than a ‘dedicated’ JW, I’m sure.

Maybe it’s an NY_JAP<->Englishman_In_NY thing, or even just an NY thing.

It’s to cover up all the hot gay sex going on in there. Like at all hours of the day and night, just non-stop sweaty pounding. People just tag out pro wrestling style when they can’t handle the hardcore sex anymore, and come back when they’re ready for more. And it’s not a few of them – it’s like 30 – 40 dudes in each place, all the time.

The whole religion thing is just a cover for it.

Not a rumor, it’s simply that maintaining a building with windows is more costly, and most Kingdom Halls are stand-alone – they don’t have minister’s residences nearby – so the buildings are more secure.

That’s not to say that they don’t have windows. The Kingdom Hall in our town does, because we’re a relatively prosperous town, the hall is near the town center (about 200 yards from the police station) and it’s large enough – I think – that state code demands they have windows.

There’s really a code about having to have windows? How bizarre. I don’t know why that should surprise me, but it does.

I mean, I know there have to be so many exits in event of fire, etc., but it never would have occurred to me to have mandated windows.

For precisely that reason. Stuff like having the lower sill x inches above grade etc. in case of snow. so if you have to bail out of a window in winter, egress is not compromised.

That’s New England for you. If they left well alone, nature would sort it all out anyway.

BLASPHEMY!!!

Ahem…

“*In Berger’s telling,* Reiner was dictatorial without the compensating advantage of genius like Stokowski.” [emphasis added]

Understood – you are not the object of my ire. Berger, however, is lucky to be dead.

Random fact: romanian fascist like individualas in the 1930 were called Legionnaire among other things

Great images to keep my attention! *wanders off aimlessly*

Good read btw.

/scrolls straight down to bibliography.

Thumbs up.

spreading Christian truth

I know to Eddie all protestants are heathens, but I would put Jehovah’s Witnesses in the same category as Christian Scientists and Mormons, just over the “not Christian” line.

My purity test is much less restrictive than the Pope’s, but there are still limits.

As you can see from the end notes, I looked at James Penton’s Apocalypse Delayed for background on the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and in their origins they had more Protestant influences than modern Protestants would like to admit!

There are degrees and stripes. Lutherans and Episcopalians still have apostolic succession; baptists not so much.

I wouldn’t even be that generous. We get hit up by them all the time in my neighborhood, and I have to fight the urge to explain “your whole religion is based on the idea that the ‘true’ name of God is a mispronunciation of mis-transliteration of a phonetic German spelling of the ancient Hebrew word Yahweh, which is pronounced no ways how you think it is. Your ‘religion’ is not a thing.”

Then I remind myself that they believe only 120,000 people are saved (by virtue of knowing Jehovah’s ‘true name’), and that they are only going to door-to-door to prove to God and themselves that the rest of us are damned and they are saved, and thus it’s really not worth the effort to engage them. It is a religion that positively celebrates ignorance.

To be fair, many many MANY religions positively celebrate ignorance to some degree. They just make it a central theme rather than the icing.

I suppose you have to admire the ‘cut to the chase’ mentality . . . .

So you limit it to variations that honor some form of the Nicene creed?

All of this inter-Christian sniping is silly. I think we can all agree that Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses are Christians and clearly all forms of Christianity are inferior to Roman Catholicism (with Eastern Orthodox being tied with the Latin church).

You filthy papists would cling to the unjustified heirarchy of the Imperial church.

“Imperial church”

I’m not an Anglican

Roman Imperial.

Sheesh, The first Anglican Empress was Victoria, the Church of England was a Royal Church at inception and is again today.

Don’t be mad

I’m merely frustrated with your bacwards ways. This is why I don’t get send to preach at people, I lack patience.

The remark was meant as a joke, wrapped in truth

And really, I’m poking fun at you.

As long as you’re not obnoxious (or violent) about your faith, I’m not going to get worked up about what you believe.

Well there’s your problem

*narrows Methodist gaze*

People who believe in Jesus and his teachings and claim to be Christian are Christians.

I agree with this and stand behind my line drawing.

I don’t think I’ve kept it a secret that I’m Mormon, and most assuredly a Christian. But we get it a lot, so I’m not offended.

Ok, while “Berger” is a homonym for “burger” in English, they are derived from different words in German. Berg is a mountain, Burg is a municipality. Hamburgers were originally called Hamburger steaks, ie “steaks” in the style of the city of Hamburg.

So… all chopped up and full of shit and assholes?

Funnily enough, my son has a classmate whose name is Harry Berger.

Parents are such shit sometimes, aren’t they?

Did he have a sister named Patty?

“We only named him after the last legitimate King of England.”

In that whole (excellent) article, you forgot to mention the significant though understated influence upon Frank Meyer by his brother Oscar.

Thanks, Eddie. This was a good read.

“U. S. Supreme Court precedent at the time held that the First Amendment rights of free speech and free exercise of religion were also protected by the Fourteenth Amendment, and thus could not be violated by state officials. The Supreme Court had exempted the states from most of the Bill of Rights, but not from these key provisions.”

This may be ironic under a thread about patriotism taken too far, but I maintain that there is something special about the First Amendment. It isn’t just what protects our freedom in so many important ways, It’s what makes us American. It’s a legitimate source of patriotism.

Things aren’t in the U.S. like they are in the UK, Canada, and Australia because of the First Amendment. Sure, there are other more outright differences, too, (see the Second Amendment), but looking at more similar things really brings out the differences in character.

The ways in which we vary from their norm is the things that make us American.

If anything, I would have liked to see the first amendment take on a more absolutist wording a la the second amendment (e.g.: The right of the people’s freedom of expression and peaceful assembly shall not be infringed.)

When someone in the UK says “You can’t say that!” they have (and have for a very long time) the threat of the machine of state behind them, and the whole process favors the guy with the most money, who is usually on the receiving end of the criticism.

Slander and libel laws over there are cudgels the rich and powerful are more than happy to wield against their critics, which they do with moderate success.

Even in Australia and Canada, Politicians sue journalists for what they write about them–without having to prove malice or damages.

The decision that find that the New York Times isn’t liable for what commenters write on their site isn’t completely unrelated to freedom of the press.

A comedian in Canada was fined tens of thousands of dollars for hurting the feelings of handicapped kid.

Never mind “hate speech” laws. We’re a different society because of the First Amendment.

The liberal interpretation of the Bill of Rights is what makes America far superior to those imitators in Europe

We decided we didn’t want to be like them in certain ways, and we aren’t.

We’re better, because of our liberal interpretation of individual rights. It goes beyond speech.

Fair enough, Ken, but I honestly don’t see the 1A as being different in kind from most of the other amendments. Sure, the one on “quartering soldiers” may be more second-tier, but the ban on government taking our guns, any of our property, searching our shit, or not giving us due process are just as important, in my book. The 1A benefits from having armies of pro-1A supporters with pulpits (namely, the media), but it is just one of several core (natural) rights protected by the BOR.

Too many words.

OT:

NFL owners have officially voted, 31-1, to approve the Raiders move to Las Vegas.

$750 million in public money.

$750 million.

*dons mirrored Ray-bans*

“A Raid upon the public treasury.”

It’s all going down a black hole.

It’s enough to make you want to gouge your right eye out.

Would this be considered a gentrification of Oakland, or a value reduction in LV? I’m sure either one gives them federal aid somehow.

$750 million in money collected from a tax on hotel rooms, and UNLV gets a new stadium out of the deal–less than a mile from campus.

Spending local taxpayers’ hard earned money for the benefit of some private entity would be really upsetting.

Taxing tourists to pay for a new stadium for UNLV, not so much.

If the presence of the Raiders in LV is so beneficial to hotels and casinos, you’d think maybe they’d directly bankroll the development out of their own cashflow, wouldn’t you, instead of using government to extort it on their behalf.

When the deal was announced, Sheldon Adelson of Sands Las Vegas Corp. was the money behind it. You know, the guy that owns the Venetian, etc.? The day after the Raiders announced they had accepted the stadium deal and were moving to Vegas, Adelson came out and said that he had no idea the offer had even been sent–he only read heard about it in the public announcement on the news. He said he was pulling his funding–but, in reality, he was kicked to the curb.

They didn’t want his money.

It’s almost certainly because of the NFL owners. They didn’t like the idea of an NFL team in Vegas, anyway, because they don’t want any of their games tainted by an association with gambling a la the Black Sox. Read between the lines, the NFL owners made a stipulation that they wouldn’t approve the move if Adelson, the owner of a string of casinos in Vegas and elsewhere, was the owner.

So they gave him the Spanish archer.

P.S. “Spanish archer” = El Bow.

“So they gave him the Spanish archer.”

These euphemisms, I swear.

Where’d you hear that Adelson was booted out? Everything I’ve read indicated he felt like he was lied to by the Raiders and the NFL and wanted out.

I said read between the lines.

They did what they did in offering the lease without any regard for Adelson–because they didn’t want him.

They got word through the grapevine that getting the owners to approve a move to Vegas would be difficult if a casino operator was involved.

Adelson’s statements in the press amount to, “You can’t fire me–I quit!”

You think he quit because they submitted a lease and got it signed without his knowledge or input?

I say when the guy putting up $650 million isn’t even consulted on the lease that’s signed, it’s because his presence is no longer desired.

They’re not going to rub his face in it in the media, and Adelson isn’t going to brag about being left at the alter either.

But that’s what happened.

“Throughout the talks, the family’s negotiators said they received mixed signals about the NFL’s perception of the city of Las Vegas and the Adelson family’s involvement in the deal.

“We just kept hearing conflicting stories about how we could do it and how the NFL owners felt about it,” Abboud said. “We felt it was conceivable that they were using that as a tool for manipulation. I don’t know.”

Then came the Jan. 26 stadium authority board meeting. Abboud transported Badain and Ventrelle to the Southern Nevada Water District meeting room. The Raiders executives presented the proposed lease, which had no mention of Adelson as a partner, to the authority staff, who made copies to distribute to board members.”

—-Las Vegas Review Journal

http://www.reviewjournal.com/sports/nfl-vegas/adelson-spokesman-withdrawal-stadium-project-raiders-were-picking-his-pocket

He was out before he knew he was out.

Looks like Adelson’s name and company weren’t even on the lease.

So, he pulled out of the deal?

Okay.

I’m sure the Raiders wish the Adelson family the best of luck in all their future endeavors..

Taxing tourists to pay for a new stadium for UNLV, not so much.

Of course, tourist taxes are the definition of taxation without representation.

The taxes are in Las Vegas–and the state legislature approved them.

That’s democracy.

Also, the hotel tax in Las Vegas will still be far below Los Angeles, San Diego, Chicago, New York, or any other convention city of comparable size.

If you’re going to finance a stadium using some form of public finance, then this is the way to do it.

No other State or city in the U.S. could probably do it this way. Vegas wouldn’t have this advantage if the other states in the country weren’t so retarded about gambling and casinos. But they do have this advantage, and it makes sense for the state legislature to do it that way.

Adelson, and his massive campaign contributions, are a huge reason for those retarded laws.

I have no sympathy for anyone in the above scenario.

The people being taxed – tourists – are not represented for the most part in the state legislature. Ergo, taxation without representation.

Sure, its voluntary to be a tourist, but the original taxation without representation was a sales tax on tea, in effect. Which it was voluntary to buy. And it was passed by Parliament, the national legislature to which the colonists were subject. Democracy?

They agree to it when they agree to pay the hotel bill.

This is the most voluntary form of taxation. If you don’t want to pay the tax, don’t book a room.

Meanwhile, if they set the tax too high, they deprive themselves of revenue.

If you’re going to finance a stadium using some form of public finance, then this is the way to do it.

Oh, I’m sure the legislators and their cronies agree that taxing people who can’t vote them out of office (and away from the trough) is absolutely the way to do it.

I bet the voters feel that way about it.

There’s more to it then gambling laws. They’ve started legalizing gambling in Ohio, albeit in a limited fashion, and I don’t think I’ve ever heard someone say they were coming to town because of the casino. Hell, one of the casinos has the absolute worst concert venue I’ve ever attended, and I was going to ska-punk shows in the 90’s at places where you were lucky if there were doors on the bathrooms.

AND they had a donkey show …

Some of the shows did have butter churners.

But it is volunatry as well.

Don’t like the tax, don’t go to Vegas

Yeah but given that tourists are going to pay 95% of that $750 mil the taxpayers of LV probably don’t care that much

(PS – Esther was the sister of Raoul Berger, not of Jesse Berger, I don’t think I was clear on that point)

Well, I think The Other Place’s comment section has completely broken down.

All I wanted to do was say ‘Stop clubbing, baby seals’ on the missing/misplaced comma story but no, four tries and still no banana.

I’ve noticed this has become more common over the last two weeks or so. It’s as if they’re passive aggressively trying to kill off the comments section all together.

Sour grapes?

But if the seals stop coming to our clubs, we’d have to go out onto the ice toe club them!

Exactly. The seals are the real problem- not my club.

Plus, honest condemnation of baby seal clubbing must first assign blame to mother nature for making their hides so desirable. What’s the point of them having such fashionable skin other than bating us to club them?

bating us to club them

That’s not even a euphemism.

I also tried like mad to comment on that story and gave up. The gist of my comment was that the decision was wrong – the comma doesn’t matter. The sentence is ungrammatical the way the unions want to read it, on account of the missing conjunction – in this case the ‘Oxford comma’ debate is a red herring.

Smells like a Glibertarian post to me!

Go for it. For some reason, the Oxford comma debate brings out the long grammatical knives. And don’t get me started on double spaces after periods!

Answer the question, counsel!

“Have you ever been, or are you now, in favor of double spaces?”

People who don’t double space after periods are barbarians. It really is that simple.

A single space after a period makes it look like you have one giant sentence.

Exactly. It’s as if they prefer a horde of sentences, crammed together nonsensical, jostling and abutting the margins as opposed to an appropriately Roman file marching — orderly — toward a victorious conclusion at the foot of the page.

Oh, I’m an Oxford comma guy and a double spaces guy.

Old school, represent!

Preach on brother!

For this reason, my chambers style guide is driving me slowly into madness.

I’ve found that Explorer usually still let’s you post comments, regardless of the state of the rest of the site. For some reason.

Given the sheer amount of hacky voodoo that their comments software has, I would be utterly unsurprised if there was an unintentional shortcut in the code due to User-Agent detection.

Hmm, at this point, not worth the effort.

“let’s”?

Seriously?

FUCKING Ohio. Lol

http://abc6onyourside.com/news/local/sex-with-animals-now-illegal-in-ohio-violators-could-face-jail-time

Poor OMWC… he just wanted to have sex with kids.

This is why I always get a signed consent form from sheep. They are very baaaaaad and lie all the time.

That’s why Scotland has so many cliffs. Get a sheep right up to the edge of one, and you’ll get enthusiastic consent. Pushback, even.

Gives another example of a “True Scotsman.”

How does a Scotsman find his sheep in the tall grass?

Very satisfying.

My Scottish buddy hates that joke.

They wear the high cut rubber boots to stick the back legs in.

You know why Scotsmen wear kilts? Because sheep can hear zippers.

Human beings are animals….

Taxing tourists to pay for a new stadium for UNLV, not so much.

Stealing from strangers is still stealing.

They pulled this same shit in Indianapolis. “We’re totally not making YOU LOCALS pay for our stadium. We’ll get it from those other guys over there.”

When it was suggested that a tax be charged on ticket sales (specifically asking the people who… you know… use the facility to pay for it) the NFL and Clan Irsay went apeshit. Fuck the NFL and their welfare-for-billionaires business model.

It was a lot to read but I enjoyed it all the same

Big thanks to those who helped rid me of my writers block yesterday.

Whoa, Eddie. Talk about burying the lead! I (for some crazy reason) actually read the footnotes and found this gem:

STEVE SMITH SURE NO ONE MIND IF HE RAPE ESCAPED CONVICT.

Frankly, I was wondering if anyone would notice that.

I enjoyed this immensely. Thank you Eddie.

Oh, there is that one photo of Felix, the first one. I am not sure what it supposed to be but I am certain it is an abomination. A crime against humanity.

Great read Eddie. Looking forward to the next part. The puns however…