In Part One, we started following the life of Raoul Berger (1901-2000).

Now in Part Two, we pick up where we left off last time. We find Berger, recently widowed, in his sixties as the Sixties got started. He took a job teaching law at the University of California at Berkeley.

“Berkeley, here I come! California sun, hippies, free love, rock and roll, marijuana, taking over the dean’s office…I hope they don’t make too much noise enjoying those things while I’m at the library studying constitutional history.”

Holding his views about the importance of history to nailing down the meaning of the Constitution, Berger was now in a position to flesh out that history. He began the first of several historical research projects seeking the meaning of the Constitution as understood by those who framed and adopted it.

Berger produced a two-part article about executive privilege in the UCLA Law Review in 1964 and 1965. These articles vehemently attacked the executive privilege doctrine, both on practical grounds and on the grounds of the intent of the Framers of the Constitution.

Executive privilege is basically part of a double standard cooked up by lawyers in the Cold War executive branch. At a time when the executive branch was engaged in massive intrusions into the privacy of the American people (with or without the approval of Congress and Congress), Presidential lawyers suggested that neither Congress nor the courts could see the private and confidential records of the executive branch or obtain testimony about the executive’s affairs, unless the President approved. The justification was that, if the President’s advisers feared having their confidential advice being disclosed to Congress and the courts, it would make them timid. Welcome to the world the rest of us have to live in – a world where things we thought were private can be revealed to the government via subpoenas and snooping.

For the supporters of “executive privilege,” one of the rhetorically most effective arguments involved former Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI), who flourished from 1950 to 1954. As a powerful subcommittee chairman from 1953 to 1954, McCarthy had been able to subpoena various government departments (such as the Army) for testimony and documents about possible Communist infiltration and the adequacy of existing procedures for keeping Communists out of the government. When we realize that McCarthy’s subcommittee was the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the Committee on Government Operations, we can see how utterly irrelevant McCarthy’s subpoenas were to anything in which Congress or the public had an interest (note the sarcasm). The Eisenhower administration had ducked and defied the subpoenas and had justified its behavior by reference to executive privilege. McCarthy’s censure in 1954 had seemed to justify the Eisenhower administration’s stance. (To be sure, the censure denounced McCarthy, not for abusing his Senate investigative powers, but for obstructing Senate committee investigations into his own conduct). Given McCarthy’s reputation as a reckless demagogue who targeted innocent people, executive privilege could be portrayed (though it was a stretch) as a necessary protection against Congressional prying into the executive branch’s affairs.

“Now, Mr. Hendrix, remembering that you are under oath, answer my questions: Are you experienced? Have you ever been experienced?”

Berger’s article said that “One who would espouse the claim of Congress to be fully informed must face up to the fact that the rampant excesses of the McCarthy Senate investigations left the process in bad odor.”

Congress had every right, said Berger, to demand information from the executive branch. The President and the bureaucracy were seeking “immunity from congressional inquiry except by executive leave.” This was wrong as a matter of policy because the executive branch had too much power already, and Congress was entitled to get information about the operation of the laws it passed and the spending of the money it appropriated. Executive privilege wasn’t necessary to protect the executive, as shown by the fact that the Kennedy administration had greatly curtailed the use of executive privilege, without any noticeable harm. The issue had not yet been settled however. The current President, Lyndon Johnson, still claimed the right to invoke executive privilege even though, like Kennedy, he was not exercising it very much. “[I]t may be doubted in light of the past, whether future successors who lack [Kennedy and Johnson’s] legislative experience will” be as deferential to Congressional demands for information.

To show the unconstitutional nature of executive privilege, Berger gave a lengthy review of “parliamentary and colonial history prior to the adoption of the Constitution, without which ‘the language of the Constitution cannot be interpreted safely.’” (the internal quotation is from this case). This history, Berger argued, demonstrated that the Constitution did not confer on the executive branch the unlimited privilege of withholding information from Congress.

“History,” Berger proclaimed, is “the traditional index of constitutional construction.” Berger did not insist that historical analysis would trump all practical considerations, but he added that there was no conflict between history and practicality when it came to the executive privilege question. “For present purposes, it suffices to regard historical evidence, not as conclusive, but as a necessary beginning upon which we can rely until, in Holmes’ phrase, ‘we have a clear reason for change.’” In a footnote, Berger reiterated his belief in the historical approach: “the Constitution was designed as a bulwark for minorities; and it can be sapped by freewheeling interpretation.” Berger commented in another footnote: “On any theory it is incompatible with the lofty role of the Constitution to ‘expand’ it as waywardly as an accordion.”

Berger’s solution was to have the courts review Congressional demands for information from Congress. This would avoid giving the final decision to the executive, and it would avoid the dangers of an opposite problem of unlimited Congressional power.

During the mid-sixties, executive privilege was a strictly back-burner subject. It was of interest to legal scholars like Berger, but as Berger himself had mentioned in his article, Presidents Kennedy and Johnson had dialed back on the exercise of the privilege. Of course, Kennedy and Johnson still insisted they had the right to block Congressional inquiries, but this sort of abstract question was not the sort of thing which would get most people excited. Certainly not in the left-progressive community, which for the moment was comfortable with the idea of broad Presidential power. With the White House occupied by Democrats who were more leftist than the Congressional leadership, progressives had no urgent need to curtail the President’s prerogatives. So they thought.

Berger left Berkeley in 1965. He ended up at Harvard, where he would become the Charles Warren Senior Fellow in American Legal History.

Harvard Gate, with its low-key, modest inscription

The fruits of Berger’s next research project came out in 1969. His work was based on a desire to find out whether judicial review – the power of federal courts to declare laws unconstitutional – was actually based in the original understanding of the Constitution. Berger also wanted to know whether Congress could limit the power of the U. S. Supreme Court to hear appeals from lower courts. In Congress v. The Supreme Court, Berger answered the first question with a yes (the original understanding justified judicial review) and the second question with a no (Congress did not have the power to limit the Supreme Court’s appellate jurisdiction).

These particular topics certainly resonated in 1969, given then-recent history. To review this history, given that my ultimate topic is the Bill of Rights, let me discuss what happened with the Bill of Rights in the 1960s, and let me in particular direct the reader to the dog that didn’t bark.

In a series of decisions in the 1960s, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren said that the states were required, under the Fourteenth Amendment, to obey several provisions of the Bill of Rights from which the Court had previously exempted them.

You may remember Earl Warren as the author of a California law by which a criminal defendant’s refusal to take the stand could be considered evidence of guilt. The Supreme Court had upheld that provision in 1947, based on the idea that the states didn’t have to respect the privilege against self-incrimination. In 1964, the Supremes said that actually, the states couldn’t force criminal defendants to incriminate themselves.

(In 1965 the Supremes clarified that this made Earl Warren’s old law unconstitutional – a defendant’s refusal to testify could not be used against him. Warren did not take part in this decision due to his authorship of the law the Court was striking down).

States now had to obey the Fifth Amendment’s self-incrimination clause. States also had to obey a bunch of other clauses which had formerly been optional for them: the Sixth Amendment’s right to trial by jury, the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishments, the right to counsel (even for the poor), the Fifth Amendment’s ban on double jeopardy, and some others. By the time the Court was finished, only a few Bill of Rights provisions remained optional for the states – minor things like the Second Amendment and the grand jury clause.

If applying parts of the Bill of Rights to the states had been all the Warren Court had done, the Justices probably wouldn’t have provoked a lot of fuss. The reason that opposition to the Warren Court grew in the 1960s wasn’t because of the Bill of Rights, it was because of the Court’s controversial interpretations of the Bill of Rights.

Specifically, the court gave three controversial decisions – Escobedo v. Illinois, Miranda. v. Arizona, and United States v. Wade. Under these decisions, federal, state, county, and city cops had to follow certain standards when investigating or questioning suspects or else their police work wouldn’t hold up in court. The cops had to allow a suspect have his lawyer with him during questioning or during a post-indictment lineup. The cops had to inform a suspect of his rights, including the right not to talk to the cops at all. If the cops ignored a suspect’s newly-enunciated rights, then any confession they obtained would have to be excluded from the suspect’s trial. In the case of post-indictment lineups held without the suspect’s lawyer, a witness who had been tainted by such a lineup wouldn’t be allowed to identify the defendant in court.

These decisions may well have been the right call, but what I want to emphasize is the nature of the opposition these decisions provoked. Opponents didn’t say that it was an outrage that the Supremes imposed parts of the Bill of Rights on the states. They didn’t object in principle, they claimed, to the right against self-incrimination or the right to a lawyer. What they objected to was the broad interpretation the Supremes had given to these rights, an interpretation so broad (opponents claimed) that it improperly assisted criminals against society’s “peace forces” (to quote Richard Nixon, who began his Presidential campaign around this time). To the critics, a suspect’s confession could be perfectly voluntary even if the police hadn’t given an explicit Miranda warning in advance of questioning, and a witness who said (s)he recognized the suspect from a lineup should be able to say so in court even if the cops hadn’t allowed the suspect’s lawyer to attend the lineup.

So here is “the dog that didn’t bark.” Whether the opponents of the Warren Court were right or wrong, what irked the critics wasn’t that the Court had imposed parts of the Bill of Rights on the states. The critics simply interpreted the Bill of Rights differently than the Court did, and they claimed that the Court’s interpretation was excessively pro-defendant.

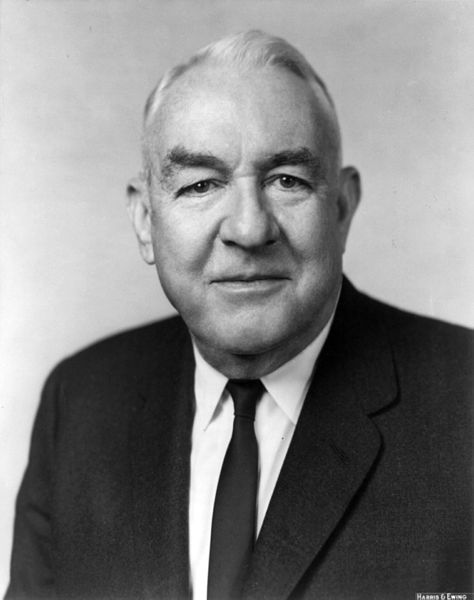

This distinction can be shown by an anti-Warren-Court proposal put forward by two influential Senators, John McClellan (D-Arkansas)

and Senator Sam Ervin (D-North Carolina).

McClellan and Ervin proposed to strip…

…the U. S. Supreme Court of its jurisdiction in certain cases. Specifically, McClellan and Ervin proposed that if a state trial court found a confession to be voluntary or decided to admit eyewitness testimony, and if a state appeals court agreed with the trial court, the U. S. Supreme Court would not have any jurisdiction to hear any challenge to the confession or the testimony (and the lower federal courts wouldn’t have jurisdiction, either). To McClellan and Ervin, this was not an attack on the Bill of Rights because properly interpreted, the Bill of Rights did not force the courts to ignore what the Senators deemed to be voluntary confessions and reliable eyewitness testimony.

(In contrast, one might question whether a confession given in police custody, by someone who hasn’t been told of their rights, is truly voluntary; one may also question whether eyewitness testimony is reliable if the witness was influenced by an unfair lineup, especially when the suspect’s lawyer wasn’t there to double-check the process. Anyway, this is a debate on the meaning of the Bill of Rights, not on its applicability to the states.)

McClellan and Ervin said their proposal was constitutional because the Constitution specifically empowered Congress to make “Exceptions” to the appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court.

While McClellan and Ervin failed in their attempt to limit the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, the controversy was still in the memory of Berger’s readers in 1969. In Congress v. The Supreme Court, Berger seemed to take the side of the Warren Court against its critics. Berger’s take on the intent of the founding generation was that they fully meant the U.S. Supreme Court to be able to exercise judicial review of state and federal laws. As to attempts to strip the Supremes of jurisdiction, Berger said this was unconstitutional. His analysis of the Founders’ intent took priority over what one would think was the clear constitutional language about “Exceptions.”

In the debate over ratification, Berger explained, the “Exceptions” clause only came up with respect to the issue of jury verdicts. Opponents of the Constitution had said that the Supreme Court might arbitrarily overrule jury decisions on factual issues, and the Constitution’s supporters cited the “Exceptions” clause to show that Congress could protect jury fact-finding from Supreme Court meddling. In contrast, nothing in the ratification debates indicated that Congress would be able to close off particular legal issues from the Supremes, as McClellan and Ervin had attempted to do. Allowing such action would contradict the Founders’ concerns about the dangers of Congressional overreach and the need for judicial checks on such overreach.

Berger concluded his book by rejecting the ideas of some Warren Court supporters that the U.S. Supreme Court should serve a policy-making role. Many progressives, unable to get their favorite policies enacted in the states and Congress, rejoiced to see Earl Warren and his colleagues impose such policies on the country in the name of the Constitution. Shouldn’t an enlightened Supreme Court provide “leadership” to a country in dire need of it? Berger said no, the U. S. Supreme Court was intended by the Founders to be a strictly legal tribunal, not a policy-making body.

The progressives were willing to forgive Berger for opposing their vision of a policy-making Supreme Court. After all, didn’t Berger’s scholarship show that the Supreme Court was constitutionally protected against the reactionaries who would hobble the Court’s ability to do justice? So Berger got a good deal of praise in progressive circles.

Now Berger turned to another obscure legal topic: impeachment.

To Be Continued…

Works Consulted

Raoul Berger, Congress v. The Supreme Court. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1969.

___________, “Executive Privilege v. Congressional Inquiry,” Part I, 12 UCLA L. Rev. 1043 1964-1965.

___________, “Executive Privilege v. Congressional Inquiry,” Part II, 12 UCLA L. Rev. 1287 1964-1965.

___________, The Intellectual Portrait Series: Profiles in Liberty – Raoul Berger [2000], Online Library of Liberty, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/berger-the-intellectual-portrait-series-profiles-in-liberty-raoul-berger (audio recording)

Adam Carlyle Breckenridge, Congress Against the Court. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1970.

Carl E. Campbell, Senator Sam Ervin, Last of the Founding Fathers. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Richard C. Cortner, The Supreme Court and the Second Bill of Rights. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

Gary L. McDowell, “The True Constitutionalist. Raoul Berger, 1901-2000: His Life and His Contribution to American Law and Politics.” The Times Literary Supplement, no. 5122 (May 25, 2001): 15.

Johnathan O’Neill, Originalism in American Law and Politics: A Constitutional History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

David A. Nichols, Ike and McCarthy: Dwight Eisenhower’s Secret Campaign Against Joseph McCarthy. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2017.

Israel Shenker, “Expert on the Constitution Studies Executive Privilege,” New York Times, July 26, 1973.

Seems mildly related to topic at hand – Hawaii judge issued a longer lasting ban on Trump’s executive order related to immigration. Note how the AP states how Hawaii proved this order would harm Hawaii’s tourism industry (lots of Pakistanis vacationing in Hawaii, I take it). And how no one has actually explained what that has to do with the legality of the order.

During “The worst discriminatory EO ever! Part 1” I returned from overseas and my aisle mate was from Jakarta. Somehow he made through immigration and got to the baggage claim in Honolulu before I did. So if an Indonesian is beating an “‘Murican” into Hawaii I doubt the tourist industry is being harmed. Not to mention why the fuck the state thinks it has standing more so than Hilton, Sheraton, Ramada, etc companies.

Curious on this part:

While McClellan and Ervin failed in their attempt to limit the Supreme Court’s jurisdiction, the controversy was still in the memory of Berger’s readers in 1969. In Congress v. The Supreme Court, Berger seemed to take the side of the Warren Court against its critics. Berger’s take on the intent of the founding generation was that they fully meant the U.S. Supreme Court to be able to exercise judicial review of state and federal laws. As to attempts to strip the Supremes of jurisdiction, Berger said this was unconstitutional. His analysis of the Founders’ intent took priority over what one would think was the clear constitutional language about “Exceptions.”

Am I to read this as Berger argued that the Supreme Court held authority over state laws and opposed Barron v. Baltimore (1833)? So, the Bill of Rights in his view applied to the states from the beginning?

I would personally agree with that position if so, but just wanted clarification.

Sorry, when he came to the Bill of Rights Berger said the states *didn’t* have to obey.

He was saying in 1969 that Congress could not limit the Supremes’ jurisdiction just because Congress disagreed with the Court’s decisions. He wasn’t saying – at that time – what kind of decisions the Supremes should make.

I may have mixed up the subjects in an awkward manner.

So, yeah, a bit of foreshadowing on my part that Berger was going to address the Bill of Rights – and I’m going to suggest he was wrong.

But in 1969, Berger was saying that the remedy for wrong Supreme Court decisions was *not* a court-stripping measure like that of McClellan and Ervin.

In my defense, I’ll add that a lot of people mistook Berger’s position as support for the Warren Court’s decisions, rather than a procedural objection to the tactics of the Court’s opponents.

We need a new acronym for Eddie’s articles, something like TL;RA.

Good stuff, Eddie – thank you. Worst strippers ever, though (and I know of what I speak).

Too Long;Read Later.

I mean, if you’re going to put a fluff-baby in there, I’ll read the whole thing.

Seriously. Don’t you just want to give him a belly scratch?

The dog, not Eddie.

STEVE SMITH SCRATCH EDDIES BELLY….. FROM INSIDE!!

Is that poll strong enough to hold up the act of those two D’s?

Great as usual…I assume. AW;RL (At work, read later)

One criticism; I have come to expect bigfoot articles in your citations. There were none. Sad!

I came for the strippers, stayed for the article.

If nothing else, Eddie knows his audience.

I wonder what would happen if this worked out in real life. Like, you see a new strip club so walk in and it’s actually a constitutional law seminar.

The late Earl Warren could tell you the two aren’t incompatible.

I came for the strippers and got kicked out and had to buy new pants

Eddie, you little tease…

I’m guessing there’s going to be something something FOIA in part 3.

Freedom of Information Act?

Yes – my thinking was the conflicts between executive & legislative branches re: how much info the executive needs to share would lead to that. If you’ve already written it, and I’m wrong, no biggie, but it seemed a natural progression given the time frame and some of the subject matter.

Also, if Raoul Berger had nothing to do with FOIA, I obviously understand why it wouldn’t be included. He just seemed like someone they’d bring in when drafting it.

That angle hadn’t occurred to me, but now that you mention it, it certainly makes a lot of sense. I can double-check.

Bear in mind that I’m probably going to miss a lot, though I doubt I’ll get many complaints about not being lengthy enough.

I did a quick check (Wiki & one other thing online) – I didn’t see anything to connect them.

I filed a FOIA request to my local circuit court on Tuesday looking for records and video of an encounter I had with the police last week. Arkansas FOIA law says that the admin of records has three to days to give you a response. Three days will be up at close of business today and I have gotten no response.

OT: I got one of those census forms in the mail. Out of curiosity, I called the hotline to see what the penalty was for not completing the survey. After some delay, they explained it would be up to $5,000. Seems a bit severe, doesn’t it?

You should spread some feces on it and mail it back to them.

fill.it out in invisible ink and tell them they have to mail you 1000 dollars for the decoder.

I would fill it out in binary or hexidecimal

Is the 1000 dollar demand in binary too?

No, that one is made with individual letters cut out of various magazines and newspapers and glued together on a piece of paper. I’m no amateur!

Draw a picture of a hand flipping the bird on it. And don’t forget to enclose an invoice for your original artwork.

Well, they’d also have to prove that you got it. Just sayin’. USPS loses shit in the mail all the time, just like a federal agency should.

Oh they make sure you got it. They send at least two if memory serves. And they have people call you to make sure you got your “anonymous” form and to tell you you need to fill it out. And then when that doesn’t work they come knock at your door to badger you to fill it out.

Purely hypothetical and definitely not my anecdotal experience. If you continue to throw out the USPS delivered ones, they will eventually Fedex it to you (lol). If you don’t respond to that one, then yes, they will send a badgery, blue-haired old lady out to harass you. Of course, she can’t harass you if you don’t answer the door, either. And she will eventually stop knocking after a couple/few weeks. … Probably. I mean, I assume. 😉

Right. My anecdote was purely hypothetical as well. I mean, how could either of us really know for sure?

It’s pure speculation all the way down!

Gonna go OT here, but if I wanted to look at the most recent list of different state budgets, tax revenue, spending, and a breakdown between state and federal aid, does anyone know where the best places to do that are? What are the most trustworthy sources?