(For prior installments of this “trilogy,” see Part One, Part Two and Part Three)

On October 7, 1873, the new American ambassador to Japan met emperor Mutsuhito and showed his credentials.

A high-level Japanese delegation, headed by Iwakura Tomomi, the minister responsible for foreign affairs, had in the previous month returned from a lengthy foreign journey, which had included the United States. The Iwakura Mission had sought to alert the West to Japan’s complaints about the “unequal treaties” forced on the country under the prior Japanese regime, the Shogunate.

After the United States “opened up” Japan in 1853-54, the U.S. and several European powers had negotiated treaties with the Shogun’s regime. Many Japanese patriots considered the treaties to be unfair and humiliating. In the 1860s, Japan went through a civil war. The victorious faction had overthrown the Shogunate and established the “Meiji Restoration” regime in 1868. The Meiji government, which ruled in the Emperor’s name, believed its predecessor had been too weak in the face of foreign pressure.

The new American minister plenipotentiary would adopt a conciliatory approach regarding Japan’s grievances.

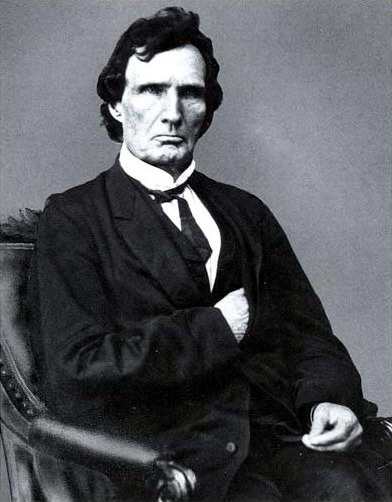

John A. Bingham was a former member of the U.S. House of Representatives, but the local leaders of Bingham’s own Republican party had denied him renomination the previous year. Bingham had left Congress under something of a cloud. He’d had dubious dealings with the crooked Crédit Mobilier company, and on his way out the door he joined his Congressional colleagues in voting themselves a retroactive pay increase (known as the “Salary Grab”). But despite some grumbling, the Grant administration and the Senate had approved him as minister to Japan.

Bingham had once been an important legislator and prosecutor when America, like Japan, was enduring civil strife in the 1860s. Bingham supported laws to conscript men, suspend habeas corpus, and to take other steps allegedly needed to win the war. During a two-year interval after he had been rejected by the voters in the Democratic surge of 1862, Bingham served as a military prosecutor. His cases included the controversial court-martial of Surgeon General William A. Hammond during the war, and the also-controversial military trial of the alleged Lincoln assassination conspirators at the war’s end.

Accused of violating the Bill of Rights with his wartime actions, Bingham replied that in the dire emergency posed by the war, civil liberties would have to be set aside.

Bingham’s constituents sent him back to the House in time for him to serve in the postwar Congress as it grappled with Reconstruction. Bingham seemed to have been chastened by his defeat in 1862 – a believer in equal rights, he’d been reminded that he could only go so far ahead of his white racist constituents. He began showing comparative caution on race – at least he was cautious in comparison to Thaddeus Stevens, whose unswerving commitment to racial equality, combined with his anger at the ex-Confederates, earned him the title “Radical.”

Re-elected in 1864, Bingham became a member of the powerful committee on Reconstruction when Congress started its postwar deliberations in December 1865. Bingham wanted to keep military rule in the occupied South until the former Confederate states adopted a new constitutional amendment – the Fourteenth. Bingham would at first be content with that, without obliging the states to enfranchise the former slaves. But Bingham, and Congress, ultimately decided that the defeated Southern states would have to reorganize themselves with governments chosen by black and white voters, in addition to ratifying the new Amendment. After taking these steps, the rebellious states would be restored to the Union.

Bingham helped shape the Fourteenth Amendment, particularly its provisions about civil liberties (Sections One and Five), as expressed in language about the privileges and immunities of citizens, due process, and equal protection. Section One was “the spirit of Christianity embodied in your legislation,” Bingham assured his constituents. Concerning the evils which the amendment would prevent, Bingham said:

Hereafter the American people can not have peace, if, as in the past, states are permitted to take away the freedom of speech, and to condemn men, as felons, to the penitentiary for teaching their fellow men that there is a hereafter, and a reward for those who learn to do well.

In this and other remarks, Bingham suggested that the Fourteenth Amendment provided federal enforcement to the Bill of Rights in the states. At one point, Bingham suggested that the 1833 decision in Barron v. Baltimore had simply denied that the feds could enforce the Bill of Rights in the states – the Court had not denied that the states were bound by the Bill of Rights. The Fourteenth Amendment would arm the federal government with the needed enforcement tools.

The Supreme Court indicated that it might ruin everything by requiring civil trials for subversive elements in the ex-Confederacy. To ensure that the U. S. military could punish ex-Confederate obstructionists without a jury trial, Bingham helped strip the Supreme Court of jurisdiction in those sorts of cases. The Supreme Court acquiesced. Bingham thought it would be time enough to allow full constitutional rights after the South had accepted the terms of Congressional Reconstruction.

When President Andrew Johnson tried to obstruct the Congressional Reconstruction program, the House impeached him. Bingham was one of the “managers” (prosecutors) in the impeachment trial, which ended with the Senate acquitting Johnson with a nailbiting margin of one vote.

With the former slaves enfranchised and the Fourteenth Amendment ratified, Congress readmitted the former Confederate states into the Union and restored civil government. Bingham kept an eye on the South, supporting the Fifteenth (voting rights) Amendment and pushing for a bill to prosecute white supremacist terrorists like the Klan. After the Klan prosecutions seemed to cripple that organization, the Reconstruction process, and the transition to a peacetime regime of full constitutional liberties, seemed complete.

Meanwhile, in the year Bingham arrived in Japan, the Japanese government took various reform and modernization measures with a view of catching up with the West. In 1873, the government, in an attempt to bolster its military, adopted conscription. Bingham would be familiar with conscription, which he pushed during the Civil War, but Japanese conscription was initiated in peacetime (though a dissident faction unsuccessfully pushed for a war in Korea in that same year).

1873 also marked Japan’s adoption of the Gregorian calendar and the legalization of the previously-banned religion of Christianity. Bingham would certainly have applauded the latter measure, even though many of the newly-legalized Christians were Catholics, not members of the zealous Presbyterian “Covenanter” denomination to which Bingham belonged. Around the same time that it made Christianity legal, the Japanese government was supervising the building of new shrines for the official Shinto religion, which focused its devotional energies on the Emperor.

As ambassador, Bingham tried to free Japan from the tentacles of the “unequal treaties”…

…agreeing in 1878 that the United States would renounce any rights under these treaties if the European powers could be induced to do so, too. Bingham wished to treat the Japanese government with respect instead of throwing his weight around and stomping through Tokyo like a giant fire-breathing lizard.

In 1878, as Bingham was showing his willingness to get Japan out from the “unequal treaties,” the secretary to minister Iwakura Tomomi published a journal of the Iwakura Mission from a few years before. The secretary, Kume Kunitake, discussed the American part of the delegation’s journey in the first of his five volumes.

The delegates were not exactly giddy as schoolgirls about their 1872 trip through the U. S….

They were not simply sightseers. As Kume’s official journal showed, the delegates wanted to find out what they could about the United States so that they could turn that information to good use in their own country. The publication of the journal in 1878 indicated that the Japanese public was expected to learn these lessons, too.

Readers of Kume’s journal learned that the delegation visited many Western and Northern states, with the visits to the ex-Confederacy limited to Washington’s home in Mount Vernon, VA. Perhaps they wanted to learn from the Civil War’s winners, not its losers. Delegation members studied the schools in Oakland, CA (“a famous educational centre in the western United States”), observed some Native Americans in Nevada (“Their features display the bone structure often seen among our own base people and outcasts”), visited Salt Lake City (“According to Mormon beliefs, if a man does not have at least seven wives he cannot enter Heaven”), visited Chicago in the wake of its recent fire (“said to have been the worst fire since the city was founded”), mixed sightseeing and diplomacy in Washington, D.C., where they reflected on the turbulence of the Presidential election (“Merchants forgot their calculations; women stayed their sewing needles in mid-stitch”), visited the naval academy in Annapolis, MD (“In America, women are not forbidden from entering government buildings”), went to see New York City’s Bible Society and YMCA (“We were suspicious of the tears of those who prayed before a man condemned to death for heresy, whom they acclaim as the son of a celestial king”), checked out West Point (“Those who fail are shamed before their relatives, but, on the other hand, this may serve as a spur to them”), and “attended a concert at the World Peace Jubilee and International Music Festival” in Boston (“Now the world is at peace, with not a speck of dust stirring”).

Kume’s journal frequently paused in its descriptions to inform the readers of the lessons the Japanese should learn from what was being described. After recounting how the delegates were able to hire an American company to ship packages to Japan, Kume added these reflections: “When Japanese merchants think of the West, they imagine some distant galaxy. When western merchants view the world, however, they see it as a single city. With that attitude, they cannot fail to prosper.” Recounting the death of Horace Greeley “of a broken heart” after he lost the Presidential election in 1872, Kume wrote: “This reveals how Westerners are willing to throw their whole heart into the pursuit of their convictions, and if they do not realise them, they are even willing to sacrifice their lives. Without such extreme virtue and endurance, it is hard to expect success in this world.”

Kume’s account of the American Civil War also seemed to point to a moral for the Japanese to follow. After describing the strength of the proslavery forces before the war, Kume’s journal said: “Faced with such determination, the abolitionists looked into their hearts and fought harder.”

Kume described how, after the war, many black people had achieved success in business and politics, thus showing that skin color was unconnected to intelligence. After noting the surge in the establishment of black schools, Kume’s journal added: “It is not inconceivable that, within a decade or two, talented black people will rise and white people who do not study hard will fall by the wayside.” Kume was marking out a path to success for any people whom whites were trying to marginalize.

The North had won the American Civil War in the name of the supremacy of the federal government. But from the standpoint of centralized Japan, the U. S. still had broad respect for states’ rights: “With its own legislature, each state maintaining its autonomy and assumes the features of a genuine independent state within the federal union….the federal government derives its power from the states; the states are not created by the federal government.”

By 1878, when Japanese readers were reading about the lessons of the Iwakura Mission’s American travels, the U. S. had already dropped a notch or two since 1872 when it came to civil liberties. President Rutherford B. Hayes, to shore up support for his contested election victory, agreed to withdraw federal troops from the South at the very time that white terrorism was resuming against the former slaves. The Supreme Court narrowed the scope of the Fourteenth Amendment, denying it the broad liberty-affirming meaning which Bingham had once attributed to it (the process had started with the Slaughterhouse decision shortly before Bingham departed for Japan in 1873).

To nationalists like Kume and his bosses in the Japanese government, civil liberties as such were not a concern. To them, Japan could not afford much Western-style individualism. As Bingham left his post in 1885 – removed from office by an incoming Democratic administration – Japanese leaders were preparing a Constitution which did not exactly embody Bingham’s vision of peacetime civil liberties. That constitution came out in 1889, and it centered political authority in the Emperor, not in the people. Civil liberties were generally subject to being restricted by law. The one similarity with Bingham’s ideas was a provision that the Emperor could operate without regard to constitutional rights during war or “national emergency.”

After his diplomatic service, Bingham told Americans that he was impressed by Japan’s Meiji leadership. Like Bismarck (and like himself, Bingham might have added), the Japanese rulers had centralized and modernized a great country. Bingham did worry about one thing – the propensity of the Japanese leadership for foreign aggression.

In his old age, Bingham fell into poverty and was apparently deteriorating mentally. His friends in Congress proposed to award him a Civil War pension based on his wartime service as a military prosecutor. To sweeten the pill for the now-resurgent Southern Democrats, Bingham’s supporters magnified his clashes with Thaddeus Stevens, whose memory the Southern leaders execrated. Bingham, the scourge of Southern “traitors,” became, in the feel-good glow of retrospect, an apostle of moderation and kindness to the white South. The pension bill was adopted. Bingham died in 1900 at age 85.

What rescued Bingham from comparative obscurity was the debate over the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment – specifically, the question of whether the Fourteenth Amendment required the states to obey the Bill of Rights – a doctrine known as “incorporation.” Supporters of incorporating the Bill of Rights portray Bingham as a James Madison figure who shaped the Fourteenth Amendment and whose vision was adopted by the people. Opponents of incorporation pay attention to Bingham for the purpose of minimizing his role or portraying him as legally ignorant.

One of Bingham’s key scholarly opponents was Raoul Berger, who referred to Bingham’s “sloppiness” in reasoning, and called him a “muddled thinker, given to the florid, windy rhetoric of a stump orator, liberally interspersed with invocations to the Deity.” Berger said Bingham was “utterly at sea as to the role of the Bill of Rights.”

Berger’s discussion of Bingham was included in his book Government by Judiciary, published in 1977. This book is a key event in the history of originalist Constitutional thought. The book took aim at key Warren Court’s decisions, in which the Court invoked the Fourteenth Amendment to justify remaking state laws regarding criminal justice, legislative apportionment, welfare rights, education, and so on. Berger presented evidence that the Fourteenth Amendment, if read according to intent of the framers of that amendment, did not achieve what the Warren court said it did.

Some of Berger’s claims proved highly contentious, even among his fellow originalists. For instance, Berger said that the Fourteenth Amendment was never meant to abolish segregated schools or to apply the Bill of Rights to the states.

Supporters of the Warren Court, the sort of folks who had loved Berger’s works on impeachment and executive privilege, took issue with Berger’s conclusions on the Fourteenth Amendment.

Conservatives, on the other hand, liked Berger’s main points, and Berger’s book became the jumping-off point for the movement of legal originalism, which conservatives liked because it exposed the bad Supreme Court decisions they opposed as illegitimate.

Ronald Reagan’s Attorney General, Edwing Meese, took up the theme of originalism in the 1980s, including criticism of the incorporation of the Bill of Rights.

In 1989, Berger doubled down on his contention that the Fourteenth Amendment does not incorporate the Bill of Rights. Berger had even more epithets for Bingham – the Congressman was “[i]ntoxicated by his own rhetoric,” his “confused utterances must have confused his listeners,” he was wrong about Barron v. Baltimore.To many originalists, who liked much of what Berger had to say, attacking the incorporation of the Bill of Rights (and attacking the Brown decision) represented a step too far. It was one thing to criticize made-up rights like welfare rights and the right to abortion, but there was nothing made-up about the Bill of Rights or about its applicability to the states.

Berger’s claim, briefly, was that the relevant provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment had been intended to validate the Civil Rights Act of 1866. This law guaranteed that with respect to certain basic rights (like property ownership and access to the courts), all native-born citizens would have the same rights as white citizens. Thus, so long as the states had the same laws for black people as for white people, it didn’t matter whether they obeyed the Bill of Rights.

Berger’s opponents said, with John Bingham, that the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to force the states to obey at least the rights spelled out in the Bill of Rights, and maybe other rights of citizenship as well.

The debate continues.

“You’ve got your Bill of Rights in my Civil Rights Bill!” “You’ve got your Civil Rights Bill in my Bill of Rights!”

(See this article criticizing originalism, and this reply. See also this critique of originalism and this response.)

Berger, who had regarded himself as a good progressive, wasn’t sure he liked the praise he was getting from the likes of Ronald Reagan, but he did not back down, defending his work in speeches and numerous articles – and even in more books.

He died in 2000 at the age of 99.

Works Consulted

Raoul Berger, Death Penalties: The Supreme Court’s Obstacle Course. Harvard University Press, 1982.

___________, The Fourteenth Amendment and the Bill of Rights. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1989.

___________, Government by Judiciary: The Transformation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977.

___________, The Intellectual Portrait Series: Profiles in Liberty – Raoul Berger [2000], Online Library of Liberty, http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/berger-the-intellectual-portrait-series-profiles-in-liberty-raoul-berger (audio recording)

Marius B. Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2000.

Kume Kunitake (Chushichi Tsuzuki and R. Jules Young eds.), Japan Rising: The Iwakura Embassy to the USA and Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Walter LaFeber, The Clash: A History of U. S. – Japan Relations. New York: W. W. Norton, 1997.

Gary L. McDowell, “The True Constitutionalist. Raoul Berger, 1901-2000: His Life and His Contribution to American Law and Politics.” The Times Literary Supplement, no. 5122 (May 25, 2001): 15.

Gerald N. Magliocca, American Founding Son: John Bingham and the Invention of the Fourteenth Amendment. New York: New York University Press, 2013.

Johnathan O’Neill, Originalism in American Law and Politics: A Constitutional History. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005.

“Raoul Berger, Whose Constitution Writings Helped To Sink Nixon,” Boston Globe, reprinted in Chicago Tribune, September 28, 2000, http://articles.chicagotribune.com/2000-09-28/news/0009280256_1_executive-privilege-writings-constitutional

![[insert joke with Jar-Jar Binks accent here] [insert joke with Jar-Jar Binks accent here]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/9e/The_Troika_1981.jpg/429px-The_Troika_1981.jpg)

As ambassador, Bingham tried to free Japan from the tentacles of the “unequal treaties”…

And that picture? Why? You just couldn’t do it, could you.

I was hoping for a nasty joke as well, maybe even a (((joke))).

Hey, no NSFW images in the posts. Now a link to something a bit more ….prurient, sure.

Berger’s position was that the Bill of Rights should not have been incorporated to the states through the 14th Amendment. You mention the disagreement that exists among originalists. I have heard many originalists argue that ‘selective incorporation’ was the real nonsense, because there was no justification for the Courts to pick and choose which rights do and don’t apply to the states. So, it seems that the Court split the baby in choosing between ‘no incorporation’ and ‘full incorporation’.

I wonder what the US would have looked like today, if instead of including the Bill of Rights, the Constitution contained much more affirmative language up front that it only grants powers within a narrow scope of the words they are described by. The fact that rights are mentioned but not granted by the Constitution seems to create some kind of idiocy-and-lies field, which appears to allow politicians to extend their own legislative powers far beyond the intended meaning of the document they are supposedly restrained by.

If we accept the pre-amble to the Bill of Rights as the context the first ten amendments should be read in, they are nothing more than a list of examples of rights the Constitution does not grant the power to legislate on. And they end with an affirmation that those rights and all others already belong to individuals and the states they live in. People already have their rights, so incorporation of the Bill of Rights through the 14th Amendment is completely meaningless.

Sadly everyone, including originalists, have bought into the idea that those rights somehow only exist because they have been written down. And most will naturally assume their own opinion supersede some of those mentioned rights, “because feelz”.

Very nice piece, Eddie- but really, the underbeards seem excessive.

Horace Greeley was really a furry that identified as a lion.

Looks more like he’s being throttled by a weasel.

Hey, you might be on to something. “He did not die of a broken heart, he was assassinated by a weasel!!!”

How can be the 4th in a trilogy?

What kind of Pinkettyian math is this?

You’re right! There needs to be at least five:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mostly_Harmless#/media/File:Mostly_Harmless_Harmony_front.jpg

(even if the 4th & 5th parts are inferior to what went before).

+4 tetralogy

Multipler effect, of course. Duh.

I’d think it would be a series if it’s more than three.

Right. Solitary, Binary, Trilogy, Series. That’s the normal progression.

I always get Frank and Russ Meyer mixed up. I like the works of both.

No love for Oscar then?

1. Big fan. One day the Wienermobile was in our grocery parking lot. The kids were very excited.

2. It’s Oscar Mayer.

3. I wish I was eating an Oscar Mayer Wiener while thinking about Frank Meyer’s philosophy and watching a Mondo Topless.

The perfect trifecta.

Would you call it a holy trilogy?

Probably (((not))))

… given the (((name))) …

That’s a nice 4th Amendment you have there; would be a shame if something happened to it.

Speaking of the 4th Amendment: Bipartisan Bill Would Require A Warrant To Search Americans’ Devices At The Border. After this, maybe they can start working on the “and this time, we mean it” bill.

Come for the articles, stay for the baby porn.

This will probably fall under the new child slave trade bill that our newest esteemed congress critter from CA is trying to get introduced. It should fly through, who’s not against child slavery?

Us?

*kicks orphan slave*

Goddammit, you just got us on the one list we weren’t already on. I hope you’re happy.

Um, OMWC might want a word.

*prolonged applause*

I just look at the pictures.

JK, I feel like I’m getting some edumencation. But how do we know you didn’t make all this up? Where are the links and sources?

*narrows gaze*

If you’re interested, there’s a novel I read a few years back that was a best seller here. Kaszoku to Yobareta Yito or “The Man They Called a Pirate”. Starts on the day the Japanese surrendered and follows the life of the founder of Idemitsu, the oil/gas company. Filled with historical tidbits that you don’t see mentioned elsewhere. The Movie. Haven’t seen it and I don’t know if there’s an English translation out, but it is an amazing story about a man that fights both the GHQ and the Japanese penchant for bullshit paperwork and collusion. He’s viewed as a nationalist hero to some, but I see him as an entrepreneur of the first class. I loved the book.

You know who else is a nationalist hero to some…

Steve Bannon?

Bannon looks like he’s been pickling in a cask of whiskey for about 20 years.

Close. Bannon is the cask, the whiskey is on the inside.

He actually looks like he’s about 6 days into a fatal dose of nuclear fallout.

Combine that with the fact that the media normally make sure he’s shown wearing that beat up old jacket and he looks like he’s just come in from 3 days of sleeping rough in the Ozarks.

“…3 days of sleeping rough in the Ozarks.”

Now THAT’S what I call a euphemism!

Anyone would think I was writing in a different language!

Obligatory.

Dude, that’s where I live. I’ve been sleeping damn near 30 years in the Ozarks and I don’t look nothing like that.

I have to love the contrast of Bannon against the too-perfect-to-be-true typical federal DC backdrop though. Like, here’s our masturbatory marble tribute to the Romans, and here’s the hobo running everything behind the scenes. It’s like if Clinton hired Hunter Thompson and he spent all his time skeet shooting on the North Lawn.

Bannon has more of a “Darius Jedburgh” vibe to him.

Due props to anyone who gets the reference without google-foo-ing.

Here’s a trailer of the movie. I’ll tell you what, the nationalists here are actually more tolerable than the “westernized” loonies I meet everyday.

Does Japan use the Georgian calendar? Don’t they use dates based on their eras? Or do they incorporate the two somehow?

Whenever I watch jidai geki, they always seem to list dates next to period names.

Gregorian calendar. I initially thought this post was about Japan’s use of the single month tax.

I’ve seen the era year as a substitute for the Gregorian year on things like coinage or side by side on calendars.

I liked The Eternal Zero, which apparently is another ultranationalist dog whistle. Not being in that audience, I guess I didn’t hear it.

Ah, it’s the same author. Explains a bit.

I take it you’ve already seen Ikiru.

(Fourth and final episode of the Berger trilogy)

*raises hand, lowers it*

He is like the Bene Tleilax, he has to put a small flaw in his every work and plot, to give the enemy a chance to escape.

OT: But so derpy I had to post

Even more derp

Strangely enough, it’s somewhat refreshing to see a good old fashioned Marxist, compared to the cultural Marxists that seem to dominate these days.

People would still want commodities under communism

And yet, who is gonna provide them?

Much less taking a chance on the new things.

And, of course, he still hasn’t solved the calculation problem.

Veering off topic, as my posts normally do, my 2nd sentence is proof of why the 3rd cant be solved. There is an argument that with modern computing power, the calculation problem is solvable, or close enough. Except there is no way to solve for new products. Would the computer give us the VCR or BetaMax? Or neither? I guess I should come up with a modern example since the last company making VCRs stopped doing it.

I wonder how many of our commentariat are young enough that they don’t know about the whole VHS vs BetaMax thing?

There’s only one way to solve the calculation problem. Put 5 guys in a room and ask them how they prefer to get their porn. That will be the optimal solution.

*awaits A grade on senior thesis*

That is easy – Pr0n Hub, and upon HM’s recommendation.

It wouldn’t have mattered comrade, because whichever arose wouldn’t have been available to you anyway.

You could update to HD-DVD and BluRay. Or XBox, Switch, and Playstation. Or Windows, Android, iOS, and Linux. Or Chrome, FireFox, Opera, and Edge.

You know, all those places where things got a lot better, really quickly.

Which one of those is an example where the experts declared A the superior technology but B won out due to its obvious technological superiority (the ability to record sporting events)?

Most of these are technologies that the “experts” wouldn’t deign to judge. But you can find holy wars and people proclaiming the technical superiority of all of them (with the exception of HD-DVD/BluRay, that battle has ended). If you want one where experts picked the losing side, I seem to remember the experts in the computer world backing the Intel Itanium 64-bit architecture over the AMD x86-64 architecture. In the end, x86-64 is what won.

Dude, I’m still rocking LaserDisc.

What always boggles my mind is how they separate the boss from the workers. It’s like the guy was just handed a multi million dollar company and he just sits in his office all day smoking cigars and counting stacks of bills. How the fuck do you think the workers got their job? How do you think they know what to even build when they come in every day? You think this shit just sprouts up organically? The boss is the one putting his money and his ass on the line. The decisions he makes literally makes or breaks the company. How is he somehow not a contributor to the value added process?

Those people have never been a boss.

We have a winner.

Because labour theory of value.

That one is my favorite – “So, the time spent painting the Mona Lisa is exactly the same I spent digging a hole in my back yard. Same ‘value’, eh comrade?”

Sad but true.. you strat from real stupid, you can only end up producing more of that..

Heinlein on labor theory of value :

My boss is a blankety-blank. He and the supervisor have made the place a nightmare to work, and think the solution is to continue the beatings until morale improves.

I’m one of the people who can take a whole lot of shit, and I’m getting irritated.

My favorite comment from that link:

*”I wish more companies would operate like this one: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alvarado_Street_Bakery“*

Too bad no-one replied to ask if it should be voluntary or compulsory.

Holy fucking mumbo-jumbo, Batman!

The difference suggests that giving the ninth vote to Judge Gorsuch rather than Judge Garland would yield a conservative vote in 29 percent more cases. Let’s call this direct effect 0.29 more conservative votes per case.

But the peer effects are even larger. The Gorsuch appointment would lead each of the other eight justices to vote in a conservative direction in 5 percent more cases than if Judge Garland were their colleague. This peer effect is roughly one-sixth as big as the direct effect, which makes it sound small. But it applies to all eight of his colleagues, multiplying its effect.

Do the math, and it turns out Judge Gorsuch’s effect on his peers would add 0.4 conservative votes per case (that’s a five-percentage-point effect, eight times over), a total impact that is actually a third larger than the direct effect (which was 0.29) of his casting the ninth vote.

Totally convincing. Seamless, ironclad logic. MATH!

*not yet peer-reviewed

I follow the math on that. Not saying it is right, but the concept seems solid.

I call bullshit on the initial 29% for a variety of reasons.

29.38% sounds far more plausible.

Is that before or after taxes?

The additional precision makes it sound more sciency.

Now all you need is a lab coat and out of date glasses and you can start applying for grants.

Now this is begging the question.

Science =

1 – covert assumptions into arbitrary numbers

2 – wave numbers in opponent’s faces and scream “Science proves [conversion of numbers back into assumption]!!”

3 – repeat

They’re gonna be filling the old buzzard full of more formaldehyde than Hillary has in an attempt to keep her animate for another 4 years.

Is there a penaltax in there somewhere?

A “Shared Judicial responsibility Payment”.

People would still want commodities under communism

Yes, they would, and this desire for commodities would inevitably manifest itself in the form of long lines of people waiting for an opportunity, however fleeting, to purchase those commodities.

(like toilet paper, or shoes)

More opportunity for graft. Oh you poor dear you’re hungry. You’re quite pretty, maybe we can work something out. Of course there is always the gulag.

Basic food items..

there is no way to solve for new products.

How many people saw the Walkman coming?

The guys who used to watch the guys who hauled wogboxes around on their shoulders all day?

What’s in a wogbox? Should I assume that it’s wogs?

For the colonials, the approved translation would be “Ghetto Blaster”, or “Polish Walkman”

Oh fuck. I did it again, didn’t I …..

You mean a boombox?

Yep, that’s probably the safest slang term.

Too late.

I forget which comedian coined the term “Minority Briefcase”…

How many employees does Sony have?

As many divisions as the Pope?

The Gorsuch appointment would lead each of the other eight justices to vote in a conservative direction in 5 percent more cases than if Judge Garland were their colleague.

*The can opener is assumed.

wogboxes

We need to run that by Robby Soave, for a ruling. Problematic, or Not Okay?

First, we have to look up the word…

Ah, it’s as I suspected, British racial slang.

Well, the British would never be racists or anything, so it’s probably OK.

/sarc

I’m 1/32 Roma, and as such am incapable of racism.

I rest my case, your honors.

So you identify as Roma?

I have Just the song for you.

I do when I’m up in front of the beak ta answer for bein’ a tea leaf. It sometimes keeps me outta the boom.

Actually, in London, it’s getting so you can identify as a cockney and get a spot on the victimhood stack.

Blimey!

Colorful cockney soldiers from London used to make up 47.9% of the British Army in the Empire.

Source: Rudyard Kipling

Join the army or descend into a life of crime and sloth. There’s a reason that “Tommy” by Kipling was a real thing. The army particularly was largely pulled from the urban underclass.

Whereas the navy was largely rural, and particularly coastal rural, because they were often pressed into service.

Crikey! Bloody limeys everywhere!

I believe that “crikey” is an Australian term.

Like many Australianisms, it’s actually English, but it fell out of favor back in the Old Country. I wouldn’t expect an Englishman to use it at all under ‘natural’ circumstances, unless he was a rabid Steve Irwin fanboi, or a regular consumer of “Neighbors” or re-runs of “The Sullivans”.

Damnit! Those stupid blokes stole it from the limeys!

I’ve brought it back. But I’m really disappointed that the limeys don’t use it today, because it sounds do limey. Like putting your bogbox in the boot of your bloody car.

Crikey, where’s my bogox? Oh, it’s in the bloody boot!

Well, it’s confusing, because Australians’ fork of English can really trip you up.

Visiting Oz as a Brit means you have to be really careful with words like shag, durex, wog, and a bunch of other words. There are Brit comedians who build whole shows around the social perils of assuming the slang terms mean the same thing.

Well it sounds cockney because a huge percentage of the transportees to Oz when it was a prison colony were cockneys.

I’ve said it back at the old place, but if you watch the Harrison/Hepburn version of My Fair lady, the guys who plays Eliza Doolittle’s father is actually an Australian, because his rendition of cockney was probably as authentic as you could get.

The limey I had as a prof in college, used to tell us about the guys they got to do tape backups in Liverpool. He said they were drunks that they pulled off the streets and gave them a bottle of booze to stay there all night and change the tapes. Bloody tape monkeys, he called them. That’s actually really funny when said with a heavy British accent.

Heh. That’s seemingly an industry-wide practice.

They used to do that at BBC Manchester I think. On one occasion, they did it at Strawberry Studios (North) in Stockport, Lancashire too – with disastrous results, I seem to remember.

Not sure I’d put some pie-eyed wino in charge of a cassette recorder, let alone a UMatic deck.

You can’t let substance abusers into the music industry!

I would have suggested this song.

While there is no question that Trump is worse than Hitler………

I know a website that you now have all the requisite skills to write for.

I don’t think they hire libertarians though.

And don’t mention on your application if you can change a tire, that would make you overqualified.

Great, now I feel bad for saying that.

Lol

It would totally blow you out.

Just tell them that you like little umbrellas in your martinis and that you sip your tea with your pinky finger out. You’re in if you just do that and repeat the Trump is worse than Hitler line.

You think flirting with ENB will help my chances? ‘Cause that would be my plan regardless.

You never know until you try.

You could consider offering to wax “The Jacket” instead, if that sounds more appealing.

Oh shit. It’s euphemisms all the way down today, isn’t it ….

How could that possibly be more appealing?

And by the way, we’re spending a lot time obsessing over the old Web site we broke up with. Our new Web site won’t like that.

Brokeback Mountain was over 10 years ago? How time flies.

I was going to steal a quote, but it doesn’t seem so edgy when you steal a quote from an old movie.

Having made a total dick of myself so far in this thread, I would like to signal my appreciation for the subject material of this and the prior 3 submissions. I can’t say *yet* just how much benefit I’ve derived from it because I’m just an I’m just an ignorant foreigner who finds Con Law new and sometimes frightening.

But I appreciate all the effort made and hope to absorb more than half of it.

*quietly sets down Kentucky Rifle and erases “Number.6” from The List*

You can’t handle the windage, man.

Groove to the penumbras and emanations, man.

Great article Fusionist. This clearly took some time and effort. Thanks.