I intend to take the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which has been mocked again and again as the very epitome of boringness, and I will make the subject…anyone?…I will make the subject interesting.

To start with, I won’t call it the Hawley-Smoot Tariff, because…anyone?…because my focus is on Smoot, not Hawley. So I’ll put Smoot’s name first.

The Smoot in Smoot-Hawley was Reed Smoot, a Republican U. S. Senator from…anyone?…Utah. We first learned about Senator Smoot in Part One, in which Senator Smoot’s…anyone?…credentials were challenged because of the whole polygamy thing. After the Mormon church, of which Smoot was a leader, dropped the practice of polygamy, the U. S. Senate decided to…anyone?…decided to let Smoot keep his seat in the Senate, to which he was repeatedly re-elected, even after Senatorial elections were taken away from the state legislatures and given to the voters.

Now, class, can anyone tell me what the Smoot-Hawley Tariff was all about? You can? And here I thought you weren’t paying attention. From your spittle-flecked responses, I can see that you can identify the Smoot-Hawley Tariff as a protectionist law passed by Congress in 1930, in the depths of the Depression, and that this law has generally been blamed for making the Depression worse. In the unlikely event there’s anyone here who doesn’t already know this stuff, here’s a Wikipedia article.

Ha ha, seriously, here’s Smoot and Hawley:

Senator Smoot is…anyone?…the one with the glasses. And the pocket with pens in it. Why can’t you students be more like Smoot, and less like that Bueller fellow? Where is Bueller, anyway?

The dynamic duo of Smoot and Hawley put forward their protectionist bill in 1929, and it passed in 1930. It is a key event in economic history, and Smoot, a hard worker with one of the best heads for figures in Congress, was proud of his work, even though it didn’t save him from a Democratic sweep shortly thereafter which put him out of the Senate.

But the Smoot-Hawley Tariff has also gotten a good deal of attention in the history of literature. To explain, let’s go back a bit.

Congress tightened up the obscenity laws in 1873, thanks to the lobbying efforts of this man, who was promptly made a postal inspector to help enforce the law. Can you identify him, class?

Yes, it was Anthony Comstock (1844 – 1915).

But this isn’t a history of postal censorship, so let’s move on from Comstock and look at the U. S. Customs.

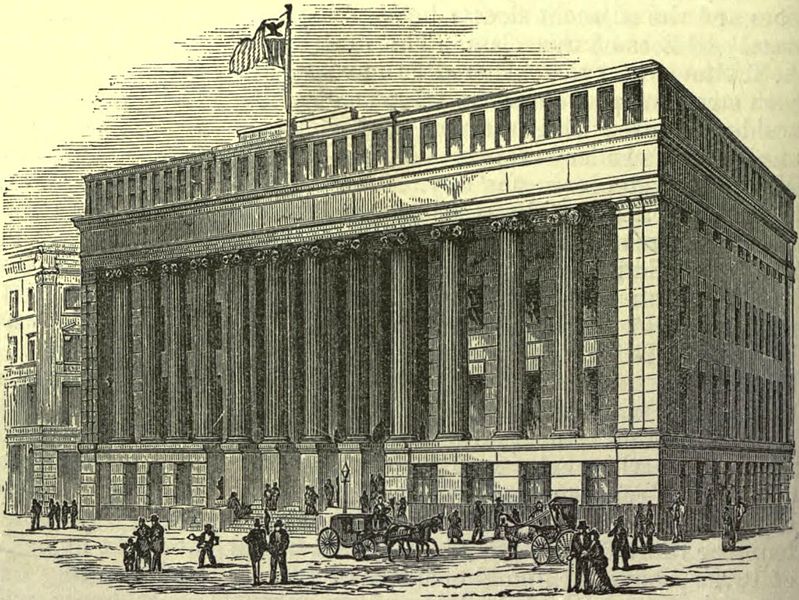

This kind:

I chose the New York City customs house for my illustration because New York City was a key point of entry for foreign literature coming into the country – or trying to come in (Los Angeles and Chicago were also key ports of entry). Until 1873, Customs officials policed a federal ban on the importation of obscene pictures and photos, but not books. The Comstock Act of 1873, in addition to dealing with the Post Office, added books and pamphlets to the list of obscene material that was to be banned. Local customs inspectors – or sometimes their superiors in Washington – had to read potentially obscene books to decide whether to ban them.

The Comstock law passed despite some grumbling that “I do not know whether it can be left to employees of a custom house to determine with safety what kind of literature or what sort of matter is to be admitted.” This Congressman finally decided to support the bill once he concluded that the decision on whether a work was obscene would be left to the courts, not customs officials.

In practice, judicial review was limited and rarely used, and the final decision on what could be imported was made by Customs officials.

The Smoot-Hawley tariff, as introduced, would have kept the existing Customs ban on obscene books. It looked like a fairly noncontroversial item, continuing the law in force, until Republican Senator Bronson Cutting of New Mexico piped up. Cutting was an arty type of Republican, indignant when he learned that a friend of his hadn’t been able to import D. H. Lawrence’s novel about adultery, Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Lawrence was actually in favor of censoring pornography, he simply didn’t think he (Lawrence) was a pornographer. He was an artist, not the same thing. Cutting agreed.

Senator Cutting [insert pun about “Cutting remarks”] proposed to take away Customs’ power to ban books on obscenity grounds. Such censorship, if it was to exist, should be exercised by the post office and by state and local governments, plus the church and the family. What qualifications did Customs people have in this area?

The Senate, in Committee of the Whole, actually accepted Cutting’s amendment. This took Smoot by surprise, and it shocked him to his core.

Smoot biograper Milton Merrill says that Smoot’s objection to dirty books was not due to some kind of repressed prurience or similar factor. Dirty books were dirty and gross, and it made no difference whether the author was some kind of artist or a good writer. There was also the fact that, as a Mormon whose moral qualifications to sit in the Senate had been attacked, Smoot was extra alert to any opportunity to rebut suspicions of dirty-mindedness.

The humorless Smoot decided to demonstrate the dangers of allowing a flood of porn to enter the country and corrupt the people, especially the youth. From the Customs officials, Smoot got copies of some of the worst porn he could find to show his fellow-Senators, many of whom perhaps were pruriently interested in this legislative documentation.

Smoot was genuinely outraged. The Senator known for his calm and detailed analyses of economic legislation spoke at the top of his voice, denouncing smutty writers like Lawrence as black-hearted villains.

When the Senate, as a Committee of the Whole, reported the bill back to itself, Smoot had a chance to challenge the obscenity provision. He wanted to reinstate the ban on importing obscene books. To be fair, this ban dated back to 1873, and Smoot hadn’t anticipated that his beloved tariff measure would be the vehicle his colleagues chose to make what he deemed a pro-smut gesture. Couldn’t Congress just keep the obscene-books ban which had been in place for over half a century, and go back to the important business of protecting legitimate American industries from unfair foreign competition?

So the poet Ogden Nash was being unjust when, in a much-cited poem, he sarcastically praised Smoot as if the Senator was inventing a new book-banning law:

Senator Smoot ( Republican, Ut. )

Is planning a ban on smut.

Oh root-ti-toot for Smoot of Ut.

And his reverent occiput.

With his outbursts of indignation, Smoot helped turn the Senate back to supporting a customs ban on dirty books. But as an experienced legislator, Smoot knew that his colleagues seemed to believe that Customs was going too far and hurting the importation of genuine, non-obscene literature. To conciliate this skepticism about Customs’ literary capacities, Smoot decided to yield somewhat and allow some reform.

For one thing, Smoot would accept an amendment by which the Treasury Secretary (as boss of the Customs Service) could allow “so-called” classics, even dirty ones, into the country on a non-commercial basis. Smoot also accepted a plan endorsed by, among others, future Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black – former Klansman and currently known as the saner of Alabama’s two Senators (this guy was the other). The Black plan would provide that the final decision on whether an imported book was obscene would be made by a federal court, in a jury trial. That ought to meet the objection that random bureaucrats were making literary decisions – the book would get a full due-process trial.

“Hey, they mutilated a copy of the Marquis de Sade’s classic Justine just so they could smuggle cigarettes!”

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff passed with the amendments somewhat softening the Customs ban on obscene books. The first true tests case involved Ulysses.

Customs believed that James’ Joyce’s now-classic work was obscene, but after the Smoot-Hawley Tariff, the publisher, Random House, insisted on taking the case to trial. Waiving a jury, Random House had the issue decided by federal district Judge James Woolsey. Both Woolsey and the literature-friendly Second Circuit appeals court said the book was not obscene and could be freely imported (at least as far as the Customs laws were concerned). Woolsey’s opinion is probably more famous than the more authoritative Second Circuit opinion because Woolsey had a gift for words and Random House put his opinion at the beginning of Ulysses.

The Ulysses case was historic because the influential Second Circuit, followed by other courts, rejected an old English case known as Regina v. Hicklin. In that case, an opinion by Chief Justice Cockburn said that a work could be condemned as obscene based only on isolated passages, based on the assumption that susceptible people might be harmed by these passages without regard to the surrounding material.

(Hicklin wasn’t the alleged pornographer, he was a lower-court judge who had tried to legalize the alleged pornography; the pamphlet in question was issued in the name of the Protestant Electoral Union.)

The Ulysses decision said that in deciding whether a book is obscene it must be looked at as a whole. Just because there were, say, sex scenes in a book didn’t automatically make it illegal – the entire book had to be dirty, not just a few bits and pieces.

Because the Ulysses case was so historic, and was decided under the supposedly literary-friendly provisions of the Smoot-Hawley Act, some people got the impression that winning court hearings for books Customs wanted to ban represented an advance for literature, making censorship tougher. In reality, importers rarely challenged Customs decisions in court, since legal challenges are quite expensive and it would simply be easier, if possible, to cut out the offensive bits designated by Customs.

Customs liberalized its treatment of books (and movies), not because of Smoot-Hawley, but because of a gentleman named Huntington Cairns. A lawyer, litterateur, and later counsel for the National Gallery of Art, Cairns informally advised the Customs service on disputed works, generally erring in favor of letting the works into the country, at a time when the Post Office and many local censors were stricter against alleged porn.

So Smoot’s “concession” wasn’t what protected literature against Customs overreach – maybe Smoot wasn’t as dumb as they thought.

Works Consulted

Paul S. Boyer, Purity in Print: The Vice-Society Movement and Book Censorship in America. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1968.

Milton R. Merrill, Reed Smoot: Apostle in Politics. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1990.

James C. N. Paul and Murray L. Schwartz, Federal Censorship: Obscenity in the Mail. New York: The Free Press of Glencoe, 1961.

There a dearth of citations for a Fusionist article.

Who really wrote this?

I could pad the citations by listing all the links I posted in the article, but I’m above that.

Speaking of dearth, not that I noticed, but there’s not a lot of comments for what I would have thought would have been a topic friendly to this site.

Is it my B. O.?

The lunch time slot doesn’t get comments going quickly until around 2pm eastern.

I only come to this site for the Fusionist articles. Your articles do take a bit longer to read than the others, though, which may explain the lack of comments at the moment

I read the whole thing before snarking at him. I was on a teleconference where I really didn’t have anything to say.

We’re all too busy trying to find these banned books.

You get a kick out of that old smoot? Whatever floats your boot…

I must admit, it’s quite cute to root for these beauts because it’s a hoot when it pisses off all these old coots.

I can’t stay mute, that is a response I must salute.

Not obscene enough.

I laughed my ass off at the “… anyone?” bit… does that count as a comment?

4/20. The Venn diagram of “people who celebrate this as a religious/cultural holiday” and “people who comment here” is not quite unity, but highly overlapping.

I didn’t think that many people would venerate Thor on his day every week…

So you’re not cool

Some of us work, you know!

So both of Alabama’s senators were in the Ku Klux Klan and anti-Catholic? Who would have thought

Keep the Catholics and anti-Catholics apart, we can’t afford more explosions.

That and the surrounding area would be saturated by high energy Raelians liberated in the Catholic/Anti-Catholic annihilation.

Ulysses was trans? Where’s his dick?

He identifies as a ‘statue’, bigot

I think the poor bastard was castrated by Catholics.

Are you blind? Look at him… he’s rock hard!

*narrow gaze*

We’ve secretly switched Vhyrus’s normal narrowed gaze with another brand. Let’s see if he notices the difference!

He’s a grower, not a shower.

They’re…not one and the same? I guess my Economics professor molested me then.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff was about *not* letting things in.

…at least not without a high tax

A tax on thingy, you say?

Potentially NFSW, BTW.

Poo poos?

Remember kids, the most intimate physical expression of the love you feel in your heart is “dirty”.

Reading? You have one twisted mind, Mainer

That Ulysses doesn’t look like he owns an unstringable bow and wins wrestling events.

Well, the others were greeks…

Ah, you Americans, so parochial and puritan. Tsk Tsk

Of course, it took until year 2000 for Canada to reign in customs and put the courts in charge of defining which obscene materials cannot be imported…

And long may Canada reign….

What was it like for Smoot and Hawley? Were people always asking where the other was, like they would with Siskel and Ebert, even though they weren’t actually friends?

You know who else wrote books that others find objectionable?

I’m still gobsmacked about a Democrat winning a state-wide election in Utah.

The Dollop had a pretty good episode on Comstock on their podcast.

It really is amazing how fucked that dude was.