Things were different in many ways a century ago, but in one respect it was like all places at all times: there were insurance agents.

Robert T. Cheek of St. Louis, Missouri, was one of those insurance agents, selling policies in his hometown for the Prudential Insurance Company. In the 1910s, after many years of what he obviously considered faithful service, he left his job and began looking for work with another insurer. He asked his former employer, Prudential, for a letter describing his work and the reasons he left.

Prudential refused to provide such a letter. Without such a “service letter” from his prior employer, Cheek had trouble getting another job in the insurance field. Insurance, as he claimed, was pretty much what Cheek knew, and he didn’t want to go into another line of work where he didn’t have so much experience. He thought he was being blacklisted.

So he sued Prudential in a state court in St. Louis. In that part of the case which is relevant for our purposes, Cheek said that Prudential had violated Missouri’s “service letter” statute. Missouri law required that an employee who had worked 90 days or longer for an employer could demand that his ex-boss provide a letter saying that he used to work for that boss, and explaining why he doesn’t work for that boss any longer.

States like Missouri which passed these “service letter” laws were concerned about employer blacklists. If an employee had crossed his ex-boss, the boss might just decide not to help that employee get new work. But if the boss was forced to give a service letter, the employee could obtain information about his work history, without which new employers might not want to take a chance on him. And if the ex-boss gave the former employer a bad reference, the employee could sue for defamation.

The trial court in Missouri threw out Cheek’s suit. Sure, Prudential hadn’t given Cheek a “service letter,” but it didn’t have to do so. Anyone, even an insurance company, has the right to free speech, which includes the “right of silence” – that is, the right not to talk.

Precedents from other states, like Georgia, indicated that service-letter statues violated the freedom not to speak, and therefore violated the freedom of speech as constitutionally guaranteed by state constitutions. Of course, a company didn’t have the right to lie about former employees – that would be defamation. But if an employer didn’t want to talk about an ex-employee, it shouldn’t be forced to talk.

Cheek took the case to the Supreme Court of Missouri, which in 1916 gave Cheek a victory and upheld the “service letter” law. Those other courts which had talked about a constitutional right to silence were simply out of harmony with the up-to-date enlightened principles of 1916. After all, all that the service letter law demanded was that a company give truthful information about former employees who had worked for them for three months or more. Disclosing accurate information – how could mandating that violate any company’s rights? The court spoke of the legislative struggle against blacklisting, and how the service letter law was a modest tool to help victims of that iniquitous practice.

Now it was Prudential’s turn to appeal, all the way to the United States Supreme Court. To defend his position, and the Missouri service letter law, Cheek had Frederick H. Bacon as his attorney.

Bacon, a Michigan native who practiced law in Missouri, had written a textbook on insurance law. Perhaps Cheek hired Bacon because of the attorney’s knowledge of the insurance industry, although this was not a specifically insurance-oriented case, but a broader labor-law case. And, as it turned out, a First Amendment case.

In those days, pretty much anyone with enough money could take their case to the United States Supreme Court. So many people exercised this right that there was a bit of a backlog, which may be why it took until 1922 for the U. S. Supremes to give their opinion in Prudential Insurance Company v. Cheek.

Most of the opinion dealt with the issue of economic freedom – in those days the Supremes still recognized the right of businesses to operate free from arbitrary government restrictions. But Missouri’s service-letter law was not arbitrary, said the majority opinion. Companies just had to provide accurate information about former employees. It wasn’t like Missouri was trying to cartelize the ice business or anything oppressive like that.

But the Supremes still had to deal with Prudential’s argument based on free speech, and the corollary right not to speak. Remarkably, the Supremes had not yet decided, one way or another, whether the First Amendment’s rights of free expression even applied to the states.

In 1907, the Supreme Court assumed, for the purpose of argument, that the 14th Amendment required the states to respect freedom of the press. But Thomas Patterson, said the Court, had abused his freedom of the press by criticizing the decisions of the Colorado Supreme Court in his newspaper, for which the state supreme court could legitimately convict him of contempt. Patterson, owner of the Rocky Mountain News and an influential Democrat, had run editorials and cartoons accusing the Colorado Supremes of acting in subservience to corporate interests when it awarded elections to Republicans and abolished home rule for the state’s cities.

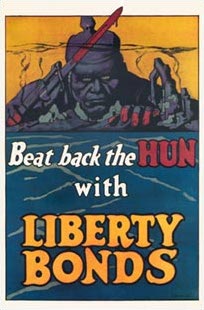

In a case arising out of the First World War, the Supreme Court assumed, for the purpose of argument, that the 14th Amendment required the states to respect freedom of speech. But Joseph Gilbert, said the court, had abused his freedom of speech, and could legitimately be punished by the state of Minnesota for making the following wartime remarks:

We are going over to Europe to make the world safe for democracy, but I tell you we had better make America safe for democracy first. You say, what is the matter with our democracy? I tell you what is the matter with it: Have you had anything to say as to who should be President? Have you had anything to say as to who should be Governor of this state? Have you had anything to say as to whether we would go into this war? You know you have not. If this is such a good democracy, for Heaven’s sake why should we not vote on conscription of men? We were stampeded into this war by newspaper rot to pull England’s chestnuts out of the fire for her. I tell you if they conscripted wealth like they have conscripted men, this war would not last over forty‑eight hours…

(If you’re interested, here is a highly sympathetic biography of Mr. Gilbert.)

In both of those cases the Court had assumed, without deciding, that the states had to respect freedom of expression. The issue hadn’t affected the outcomes of those cases because the Justices didn’t think freedom of expression applied to the insidious activities of Patterson and Gilbert.

Now, suddenly, the Justices decided it was time to make an official ruling: Do the states have to obey the First Amendment? In other words, do the basic rights protected by the Fourteenth Amendment against the states include free expression (subject to common-sense regulations such as suppression of wartime dissent)?

Here’s how the Supremes answered that question in Cheek’s case:

the Constitution of the United States imposes upon the states no obligation to confer upon those within their jurisdiction either the right of free speech or the right of silence….

Cheek won, and Prudential and the First Amendment lost.

Apparently, Cheek was able to get back into the insurance business. When he died in 1926, his death certificate said that at the time of his decease he had been an insurance agent for the “Missouri State Life Co.”

The year before Cheek’s death, the Supremes were back to their old tricks, refusing to say whether states have to respect the First Amendment’s rights of free expression. This was in a case involving a Communist firebrand, Benjamin Gitlow, who had written a manifesto advocating revolution. In a key paragraph, the Court said:

For present purposes we may and do assume that freedom of speech and of the press-which are protected by the First Amendment from abridgment by Congress-are among the fundamental personal rights and ‘liberties’ protected by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from impairment by the States. We do not regard the incidental statement in Prudential Ins. Co. v. Cheek…that the Fourteenth Amendment imposes no restrictions on the States concerning freedom of speech, as determinative of this question.

Then the Supremes went on to do what they had done in the cases of Patterson and Gilbert – they declared that Gitlow had abused his First Amendment freedoms and could rightly be punished for it, even if the First Amendment applied to the states.

(Gitlow later left the Communist Party and published a memoir entitled I Confess: The Truth About American Communism.)

So it was back to the old drawing board – the applicability of the First Amendment to the states was still officially unresolved.

In two key cases in 1931 (here and here), the Supremes finally decided that the states did have to obey the free-expression guarantees of the First Amendment.

The first of these decisions said that both the federal and state governments have to respect your right to wave a communist flag. The second decision said that the government (whether state or federal) can’t shut down a newspaper as a “public nuisance.”

(Here is a book about the freedom-of-the-press case, Near v. Minnesota).

Neither in their published opinions nor in their private papers through 1931 did the Justices engage in any detailed examination of the question of “incorporation” – whether the states had to obey the First Amendment and if so, why. The Supremes just veered from one side to another, almost as if they were flying by the seat of their pants and not acting on any coherent principle. It was only later, in subsequent cases, that the Justices began working out various rationales for applying the First Amendment to the states (TL;DR version – because free expression is a Good Thing and is Good for Democracy).

A good guess would be that, when the Supremes were unenthusiastic about free expression, they weren’t that interested in imposing it on the states, but when (as in the 1931 cases) they got interested in free expression, they decided it was time to make the states as well as the feds respect that right.

Many states still have service-letter laws to this day. Check your local listings.

Works Consulted

Floyd Abrams, The Soul of the First Amendment. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2017, pp. 60-62.

“Anti-Blacklist Law Upheld,” Iron County Register (Ironton, Missouri), December 7, 1916, http://bit.ly/2rjmnTh

Ruth A. Binger and Tracy R. Ring, “BEWARE – PROCEED CAUTIOUSLY – WHAT THE MISSOURI EMPLOYER SHOULD KNOW ABOUT THE SERVICE LETTER STATUTE AND DEFAMATION.” St. Louis: Danna McKitrick, P.C., Attorneys at Law, WWW.DANNAMCKITRICK.COM, 2003.

Vickie Caison, “Bacon, Frederick H.” Friends of Silverbrook Cemetery, last updated November 22, 2010, http://www.friendsofsilverbrook.org/site4/obituaries/95-bacon-frederick-h

Russell Cawyer, “Texas Has No Enforceable Service Letter Statute,” Texas Employment Law Update, December 2, 2011, http://www.texasemploymentlawupdate.com/2011/12/articles/human-resources/texas-has-no-enforceable-service-letter-statute/

“Robert T. Cheek,” St. Louis, Missouri City Directories for 1910, 1913 and 1916, Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2011.

Richard C. Cortner, The Supreme Court and the Second Bill of Rights: The Fourteenth Amendment and the Nationalization of Civil Liberties. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1981.

“Frederick H. Bacon,” Find a Grave, https://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=gr&GSln=bacon&GSfn=frederick&GSmn=h&GSbyrel=all&GSdyrel=all&GSob=n&GRid=60501380&df=all&

Klaus H. Heberle, “From Gitlow to Near: Judicial ‘Amendment’ by Absent-Minded Incrementalism,” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 34, No. 2 (May, 1972), pp. 458-483

“Labor and Employment Laws in the State of Missouri,” Fisher and Phillips LLP, Attorneys at Law, www.laborlawyers.com.

“Master and Servant: Blacklisting Statute: Failure to Give Service Letter,” Michigan Law Review, Vol. 8, No. 8 (Jun., 1910), pp. 684-685

Ruth Mayhew, “States that Require an Employment Termination Letter,” http://work.chron.com/states-require-employment-termination-letter-24010.html

Missouri State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, Death Certificate for Robert T. Cheek, St. Louis, Missouri, c. March 1926 [courtesy of Ancestry.com]

“Online Books by Frederick H. Bacon,” Online Books Page, University of Pennsylvania, http://bit.ly/2r9YTDm

Robert Gildersleeve Patterson, Wage-Payment Legislation in the United States. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1918, p. 75

James Z. Schwartz, “Thomas M. Patterson: Criticism of the Courts,” in Melvin I. Urofsky (ed.), 100 Americans Making Constitutional History: A Biographical History. Washington, DC: CQ Press, 2004, pp. 154-56.

Ralph K. Soebbing,”The Missouri Service Letter Statute,” Missouri Law Review, Volume 31, Issue 4 Fall 1966 Article 2 Fall 1966, pp. 505-515.

Forget the article; i am far more concerned that there might be some error in the formatting of these footnotes.

e.g. periods after page-numbers? It is inconsistent. Must find rule.

Uh oh, looks like Eddie’s being audited. You best get your MLA on point son.

You put the white in Strunk & White.

I put the funk in Strunk, yo

I just wanted to mock Eddie’s pedantic instincts by saying, “You missed a spot”

Maybe I’ll wear a non-matching tie just to annoy you.

(to Gilmore)

I have seen no proof that you are actually wearing pants.

Your dress-code is irrelevant to the ‘Missing Periods after page-numbers’ issue. (see: 9th, 11th, 15th footnote) Highly irregular.

OMG, irregular periods! Could I be pregnant?

It’s my right as a man, you know.

EW

So, how does a potential employer verify an individual’s resume? I had to use tax records when I was hired recently, but in our perfect utopia there won’t be any of those, so then what?

An employment records clearinghouse would be one possible answer. Employers who want to be able to pull references have to also provide them.

Don’t they usually just call the employer? Most will verify employment, though they won’t provide details beyond job title and dates of employment.

That is the normal way of doing things, yes.

For some reason my job from 10 years ago doesn’t want to verify me anymore. I have had 2 companies this year that made me send them my tax info. But that goes back to my original post. What if your employer for whatever reason doesn’t want to confirm your employment?

Then it’s not confirmed, and it’s up to your prospective employer to decide how much that matters to them.

That seems to put a lot of power into your former employer’s hands.

Right. I mean, if I were calling on someone’s references and one of them pulled a Prudential, how would that work? “I can neither confirm nor deny that Ms. Whatsherface was employed by our company”? I would think at that point that the prospective employee could just imply that they were the victim of some sort of malfeasance and either provoke the former employer into saying something slanderous or just have it all their own way. I had an employer where I spent a lot of time but parted on bad terms, and subsequent employers called, got the “Yeah, he worked here, he resigned, we wouldn’t rehire him,” and, when asked, I explained the situation to them: “I was hired for one job, but was shoehorned into a very different job. After a couple of years of being told they were working on getting me into the expected position, they hired someone else. I felt like they were taking advantage of me and left.”

This story started before the federal income tax so no luck there. The Prudential management may have been in the right, but they were some determined assholes in this story.

Fascinating read, Eddie. Keep up the good (and painstakingly sourced) work.

Fun* fact: apparently “blacklist” and “whitelist” are racist terms even though their etymologies have nothing to do with race.

* = not really

“Everything is sexist, everything is racist, everything is homophobic, and you have to point it all out.” Anita Sarkeesian, explaining why social justice activism is cancer.

social justice activism was good business for old Anita.

And more power to her. Taking money from dummies is a respectable profession.

I hate that I find Anita S. quite attractive.

She’s not as hot as Andrea Dworking in a skimpy bathing suit

Dworking = feminist twerking?

I dunno, but you might be more interested in Dorking.

It looks lovely, but…you know, England.

My assessment of England was “Looks like Upstate New York with fewer hills”

Sex negative twerking.

Twerking is already a way of making otherwise attractive women ugly.

It makes unattractive women downright vomitous.

Why this link is not Rick Astley bothers me.

I have to agree. Reprehensible person, but yeah, definitely would. Hey, anything that shuts her up is a service to us all, amirite?

Here’s the clip – then it provides some context

“at the time of his decease”. Is that right? The more I say it, the weirder it gets.

“At the moment of his demise…”

“When ______ shuffled off this mortal coil”

“When he snuffed it, ___________”

No, no. It’s not dead. He’s just resting. Remarkable bird the Norwegian Blue.

Yeah, it’s awkward.

“Right up until he croaked he was an employee of the etc.”

Still interesting read. Thanks.

“To Whom it May Concern,

Mr. X was employed by our company, as a Personal Lines Agent from August 1911 to September 1912. In that time, he distinguished himself as the largest blot on our customer satisfaction and renewal rates that our Company has ever seen. His firing led to tears of joy from ever girl in the secretarial pool, as well as the boys in the mail room.

Sincerely,

The Mutual Insurance Company of __________”

I’d be a bit more cautious.

Something like “you would be very fortunate indeed to get this applicant to work for you.”

Related: See chapter 23 of The Dilbert Principle.

Silver bullet defense – when asked to donate employees, managers will unload their most incompetent workers

(note the ambiguous phrasing)

DEFAMATION

“See the attached 47 affidavits from secretaries, mail boys and customers”

Channels inner Richard Dawson:

“The Mutual Insurance Company of Oma-ho.”

Inn-Sewer-Ants: the translation of an Agatean concept brought to Ankh-Morpork by Twoflower. The idea was that a financial institution, upon payment of a yearly “premium”, would guarantee reimbursement of loss of property due to fire or other disaster. This must have worked well in the Aurient, but Morporkians soon found the opportunity to reap windfall profits of thousands of percent irresistible. The ensuing chain of events included the Great Fire of Ankh-Morpork, the formation of the Firefighters’ Guild, and Charcoal Wednesday.

This is all I have to contribute

Actually one more thing. Is there some sort of historical record for the US for the rate of lawsuits per population? Were people suing each other more often in say 1910 then now?

No. Litigation really took off in the 1970s. A common expression was “sue the bastard!” See also Ralph Nader and his various organizational outgrowths, “Right of Private Action” in many “Discrimination” laws, etc..

Well you got some sort of reference for that? It’s not that I don’t trust *you*, but in general people who are indentured to the Swiss can be shifty

Trust me, I am a lawyer….wait…um…

Warning, pdf: https://gspp.berkeley.edu/assets/uploads/research/pdf/ssrn-id2184562.pdf

I mean I could try googling but I prefer for other to enact my labor for me

Me reading this comment.

I know the regard with which the author is held in some circles, but the only thing that came to mind was “You know policies don’t pay out in cases of arson instigated by the policyholder, right?”

They do in Ankh-Morpork.

I find the author amusing in small doses but hes not my favorite.

I’m still not seeing the humor.

That does not mean it’s not there

In fairness, the series really doesn’t get its legs under it until the fourth book. Honestly, you could skip the first two and not miss out on too much. The rest of it is, and I swear to god I have no financial relationship with the author’s estate, brilliant satire, insightful social commentary, and shows a remarkably dry wit. People who like Douglas Adams tend to like Terry Pratchett. Personally, he’s my favorite non-horror author.

He’s one of my favorites as well. Books like Jingo and The Truth are hilarious in their accuracy.

The dude understood human nature like few other autors.

Or, you know, ‘authors’.

*grumbles*

In fairness, the series really doesn’t get its legs under it until the fourth book.

Part of the genius of the Discworld books is that they break into several sub-series that are fine as stand-alones, but have enough crossover that the whole is greater than the sum.

Personally, I’d recommend the Night Watch series and the Industrial Revolution series. The witches and the wizards stories just aren’t quite as good, IMO.

Some quality Reddit derp, but from a supposedly conservative POV:

https://www.reddit.com/r/The_Donald/comments/6bd0th/when_you_meet_someone_from_marchagainsttrump_and/dhlnen9/

For the last time you morons, this isn’t how German works.

Oh, read the argument now.

That’s classic command economy stuff right there. “If I think it’s useless it’s not really growing the economy.”

The dude somehow was able to read some Austrian school stuff, but he didn’t actually understand much of it. I am trying to be somewhat polite, but it’s wearing my patience a bit thin.

I don’t understand what the point of that was.

I also don’t understand why anyone thinks the term “Drumpf” does anything other than make the speaker/hat-wearer look like a child.

I realize there were people who insisted on referring to Obama as “Obozo / Block Insane Yomomma*” for 8 years, but they were largely confined to anonymous morons in comment sections. People generally did not parade these terms around in public expecting to be taken seriously.

*h/t Mike/DomesticDissident

having read it again, it appears that the point is that Timmy is an idiot

Personally, I liked Obumbles, but that’s just me.

The Light Bringer was my favorite epithet for the man, hands down. It also had the benefit of being used about him unironically by hero cult morons.

I preferred ‘the anointed one’. Chocolate Jesus is a close second.

Chocolate Nixon, please.

Il Douche was my favorite.

Chocolate Nixon was the best.

I also don’t understand why anyone thinks the term “Drumpf” does anything other than make the speaker/hat-wearer look like a child.

Chortle. You’re talking about a class of people that are inclined to make oversized paper mache cartoon heads as a cutting political criticism.

Leave our papier maché heads alone!

Is a service law needed at all to protect against defamation? An employer who baselessly accuses a former employee of malignant or incompetent work history leaves himself open to accusations of slander, right? I wonder whether a company could be accused of defamation for insisting that a former employee never worked there.

The service letter law was not for protection against defamation.

I suppose I should have asked: doesn’t routine defamation law already protect employees from vindictive employers (and vice-versa)? Protection from untruths is already a thing, so compelling speech shouldn’t be necessary.

From my limited research, if you were on a blacklist, your ex-employer simply wouldn’t share info about you at all, on the theory that it’s not defamation if you don’t say anything. But the silence was loud enough you could hear it for miles.

I’m trying to work out how that affects employers who know their competitors are withholding information. It sends important signals regardless: if the applicant is a lout with shoddy workmanship, a rival should be willing to give him a sterling review because, hey, he’s your problem now. The applicant certainly isn’t going to dispute the undeserved plaudits. On the other hand, they can’t lie about what a piece of shit he is without risking a lawsuit. So their silence implies they don’t want you to hire him, implying the guy may be an asset they regret losing.

I’m also curious just how common this practice was.

I’m afraid my research into blacklisting in general wasn’t very extensive.

I know my granddaddy was blacklisted, with a list posted on the factory gates about union members who need not bother re-applying after a strike.

But I think he got other work, probably not from the same company IIRC.

Actually, a lot of places don’t want to say anything because they fear being sued by the potential employer for falsely representing the person.

In Maryland, I believe it’s still the case that an employer is legally prohibited from volunteering information about an ex-employee other than verifying employment dates, giving the reason and nature of the separation, and saying whether or not they would be _eligible_ for rehire. Obviously nobody pays attention to that, but last I heard that was technically the rule. So you could say that so-and-so worked at your company for two years, was fired for excessive tardiness, and wouldn’t be rehired, but you couldn’t say that so-and-so was lazy as shit, never showed up on time, always had an excuse, and generally sucked.

I believe it’s still the case that an employer is legally prohibited from volunteering information about an ex-employee other than verifying employment dates, giving the reason and nature of the separation, and saying whether or not they would be _eligible_ for rehire.

Sounds like another violation of the 1A.

(I’m probably going overboard with the homo economicus thinking. No doubt there was some tacit understandings among the good ol’ boys for respecting blacklists.)

Not everyone thinks the same statement or lack thereof will be taken the same way. So there is no one rule for “what does silence mean?”

Or the guy may just be lying and claiming experience on his resume that he does not have. That is the whole purpose of it, when a company hires a guy who says he has 15 years experience selling insurance they want to make sure he actually does and that he is not just trying to get a job through any means possible.

Pennsylvania does not have a service letter law, but does provide some protections for employers if they provide one. So no, not required. Most PA based companies are still very reticent to write then even with the protections though, as it is easier to just avoid a potential lawsuit. All you’ll typically get is the early verifiable and objective facts of start date, end date, compensation history, and titles held.

I was under the impression that was the data a service letter law would compel.

That’s just metadata. The feds are on top of it already.

Depends on the state. Pennsylvania’s defamation protections only apply to facts, and things such as the reason for termination can be rather subjective. As such, PA employers will generally not disclose such things. Colorado on the other hand has a service letter law that requires employers to disclose the following:

• job performance

• reasons for termination or separation

• knowledge, qualifications, skills, or abilities

• eligibility for rehire

• work-related habits

All of which have done level of subjectivity to them. If a Pennsylvania based employer wrote a service letter with that information, their legal department would go on a warpath.

I find Colorado’s requirements abhorrant from the summary provided. Remind me never to work in that state.

Deal, assuming you return the favor and expand it to never running a business there, either.

I will not base in the state, but I will not rule out selling to people in the state. (I can’t tell Amazon “sell everywhere except Colorado”)

It’s pretty shit.

But there are some things going for us out here.

Donetsk, don’t tell.

*narrows gaze*

Great work, Eddie. I look forward to reading the Gilbert book.

Jerry Garcia’s guitar to go up for auction again.

Pritzker, who occasionally loaned the guitar to musicians, decided to put it back on auction, announcing that all proceeds would go to the Southern Poverty Law Center, which wages legal battles against white supremacists and other hate groups.

“He called me three months ago to say he was concerned about the divisive things that are going on in the country and wanted to do something meaningful,”

——-

Well, good thing there are people still out there willing to fight the good fight.

The SPLC? Why would anyone donate to that Hate Group?

What!?!

You want to see Morris Dees reduced to panhandling on street corners or becoming a wage slave like you?

-We haven’t been paid in two weeks and we want our wages!

“Wages? You don’t want to be wage slaves, do you? Answer me that!”

*all* NO!

“Of course not, but what makes a wage slave? Wages! “

Wage Slave?

I will have you know – I am a Salaryman!

So you avoid going home at all costs and spend all night signing karaoke and swilling Sapporo?

That would require me to be around people.

Well, Japanese, anyway.

signing karaoke

Even the deaf can enjoy the wonders of shitty renditions of popular songs!

I’m inclusive, baby. So woke!

Reminder = The people in question are “Deadheads”

They can be a bit slow to catch on.

They’re doing the hard work of going after cartoon frogs and parodies of identity politics and accusing them of being racist.

I love how the comment section of that article is pure diarrhea. Here’s one that isn’t a deleted top-level comment:

James Rustle • 6 days ago

I’ve just found out that my wifes son has one of those “Kek” flags in his room, although he is not “white” I’m afraid he might be mixing with the wrong crowds, recently he’s become very active in politics, and unfortunately he has fallen for the “Dark side”. cough..Drumpf..cough

::facepalm::

I still to this very minute cannot figure out why ‘Drumpf’ is in any way shape or form an insult. I even googled it and google couldn’t tell me. Apparently it is literally ‘hur hur I spellz it funnay! I are clevar!’

It’s idiots repeating John Oliver like a trained parrot because he’s ‘smart’, while Oliver’s original point was a combination of “DUR HUR TRUMP IS AN IMMIGRANT” and “DUR HUR TRUMP IS GERMAN, THEREFORE NAZI”.

And of course, because the people who claim to use ‘reason’ and ‘facts’ are in reality complete retards who don’t actually research anything before opening their mouths, Trump’s family never changed their name, it has to do with the fact that German didn’t have standardized spelling until the late 19th century. Trump’s grandfather’s name is listed as ‘Trump’ on his baptismal record and ‘Trumpf’ on his immigration form, because the person spelling it was likely used to a different German dialect.

Damn your much more thorough, quick, and excellent hands.

YOUR INSISTENCE ON ACCURACY AND FACT IN THIS MATTER MEANS YOU ARE A DRUMPF SUPPORTER

Drumpf is supposed to be a hilarious takedown on how his German grandpappy was an immigrant. At least that’s what I gather.

Trump’s grandfather’s name was “Drumpf”, and he (or immigration officials) anglicized it to “Trump”. How this is an insult, I’m not exactly sure.

One of my ancestors saw his name Anglicized from Hautot to Hutto several hundred years ago. Talk about an absolute scream!

Related: How The Dutch Got Their Funny Names

Also very telling how he specifically denies ownership and others the fuck out of step son by calling him ‘my wifes son’. Grade A parenting there shit bag.

The “wife’s son” means that is a troll post. The memer/kekistani brigade loves to throw that little bit of humor in when they make their troll posts and comments.

IHBT

That’s probably trolling, the attempt to infer that he’s a cuck is telling.

Wait, “kek” is racist now? It’s been a meme on Twitch and other gaming sites for a while.

It’s the SPLC, the people who list ex-Muslims critical of Islam as Islamophobes. What do you think.

I used to play world of tanks a bit and saw it all the time. I thought it was Russian for “LOL”.

Nerdier than you can possibly imagine.

Kekeke used to be the ol’ Starcraft Korean for “hahaha”, but “kek” came from WoW where the different faction players couldn’t read the others’ chat. If Horde players wrote ‘LOL’ it would go through a translator and come out as ‘KEK’ to Alliance players. So it became its own thing as a result.

In meme culture it really exploded after they released there was an Egyptian god of the same name and claimed divine intervention.

IIRC, Koreans used “kekekekeke” as an onomatopoeia for laughter in Starcraft chats.

When Blizzard created World of Warcraft, they scrambled communication between Alliance and Horde players. When a Horde player typed “LOL” in chat, an Alliance player would see “KEK”.

There was a corresponding code on Alliance-to-Horde side, but I never played Horde, so…

O Y O in Common translated to L O L for Horde players. So you could understand the full extent of your beat-down while a Human paladin is teabagging your corpse and spamming O Y O.

Kek’s male form was depicted as a frog-headed man

God damnit, that fucking Pepe shit is never going to die.

Blame the normies for making it a ‘white nationalist’ symbol, now it’s just too good not to troll with.

It’s the History Eraser Button 101.

I get that it makes me an old fuddy-duddy, but I hated that thing before it was a thing. When the media started evacuating its collective bowels over it, I was like Elaine and the English Patient.

And I have to wonder how many people associated with Ren & Stimpy were involved with Duckman.

That’s a whole lot of memerry right there.

Pritzker, huh? Obama’s favorite family of cronies.

I don’t think I’ve seen this one linked here yet – the unbearable oppression of wood paneling.

I would love to oppress her and her ilk under 100 years worth of wood paneling.

Wood paneling’s got nothing on a good eggshell plaster.

Wood.

*ducks behind paneling

Marginalized by wood paneling. It’s beyond parody, really.

Related:

The only true safe space is in a pine box.

minority students felt marginalized by quiet, imposing masculine paneling

Don’t know about you, but I’ve never had wood paneling that made any noise. Isn’t it all quiet?

Imposing? Seems an odd word to use for paneling, but OK, I guess.

Masculine, though. Was it cut from male trees? I’m guessing not, since most trees are hermaphroditic. Maybe its a species that does have single-sex trees, but even then, how would you know it was the male trees that supplied the panelling?

If you examine the grain of the wood under a microscope, the cellular structure spells out “PATRIARCHY” in tiny letters.

So clicking on Chipwooder’s article led me to another article on a Palestinian terrorist speaking at a SJP chapter which brought me to this fawning article about her on Jezebel. Come for the fact-free accusations against Israel in the article, stay for the blatant antisemitism in the comments.

That’s Jezebel hitting on all cylinders there:

Oh God, don’t I know it! Well, it’s worse than the few years after 9/11 if you, y’know, weren’t a family member of one of the 3000 people who were incinerated or crushed by 1500 feet of skyscraper collapsing on them, like my cousin. Other than that, the Trump scourge is totally worse.

And by “trailblazing intellectuals, activists, and leaders”, they mean Communist scum who ran off to a murderous dictatorship.

Because nothing says white nationalism like support for Israel.

Correct me if I’m wrong, but I believe there’s a certain woman from Somalia who receives less than glowing coverage from the likes of Jezebel.

Heard from the Volga Germans lately, or the East Prussians? What makes Palestinian Arabs so special?

blah blah blah…..fucking thing does on forever. And I thought George Mason was one of the few non-loony law schools out there, yet they employ this twit?

Apologias for a terrorist. The three kids she killed were minding their own business, in a cafe IIRC. That she was righteous in her own mind (and apparently still is) and that other people apologize for her, is disgusting.

Restraint is not an accepted concept for the Progs or the Muslims.

Remember when Trump knifed that Omani dude right before the election?

Or at the inaugural ball when he beat some gay Egyptians with a lead pipe?

I have a friend whose ancestral home was in East Germany before WWII. It now belongs to the German state. Perhaps he should have blown up a few schoolchildren on busses to make a point?

Maybe its not where she’s from, or that she’s a woman, but the fact that she murdered three Israeli students, that has people upset with her.

It’s articles like these that make me wonder what bloody planet the alt-right lives on where the left never criticizes Israel and is always secretly protecting (((them))).

This will end well.

I think I can fap to this. Fingers crossed.

Crossed fingers? Interesting technique.

I tried backhand Style but the carpal tunnel really flamed up so I’m experimenting.

Flesh light?

I don’t think I have ever watched a President’s speech. I would watch that.

About the best thing the U.S. government could do for not only the benefit of its citizenry, but for the whole world, is end the tail-wagging-the-dog alliance with the Saudi monarchy.

The Wahabbists are fucking worthless savages, and having the U.S. act as their military arm and patsies has been quite disheartening. And when they stop chopping off heads of atheists and crucifying gays, maybe they can be worth something to the rest of humanity.

Trump, “I have come to you today King Salman, to talk about the problem of whabbist Islam. This fundamental Islamic sect is responsible for a great deal of death and destruction in the ME and abroad. I would like for you, most favored ally, to assist the United States in rooting out this ideology.”

King Salman, “sure, we will get right on that. We of the House of Saud have always been against whabbism in all its forms.”

Only Trump could go to Saudi Arabia?

Can I get an over/under on Trump pitching the idea for a wall around Mecca?

To protect it from the Wahabists that want to destroy idolatry?

“Guys, have you been reading American newspapers again? Don’t read them. You can use them in all sorts of ways, but don’t read them – it’s not just bad for you, lately it’s been dangerous.”

– Maria Zakharova, (smoking hot) spokeswoman for the Russian foreign ministry

From article that I saw posted on someone’s wall on FaceDerp:

“Congressman Rod Blum in a Dubuque town hall hall Monday night asked, ” Why should a 62 year old man have to pay for maternity care?” I ask, why should I pay for a bridge I don’t cross, a sidewalk I don’t walk on, a library book I don’t read? Why should I pay for a flower I won’t smell, or a park I don’t visit, or art I can’t appreciate? Why should I pay the salaries of politicians I didn’t vote for, a tax cut that doesn’t affect me, or a loophole that I can’t take advantage of? it’s called democracy, a civil society, the greater good. That’s what we pay for.”

I wish people would get it out of their heads that democracy in and of itself is an unfettered good. Democracy without a guiding set of principles is no worse than monarchy, or oligarchy.

*No better, not worse.

In some ways it is worse. It is mob rule. With a monarchy you have 1 person or a small family keeping order. With straight democracy you have whoever has the most manpower on top at all times, which can lead to some very ugly things happening.

In most ways it is worse

most manpower on top at all times

Phrasing?

With straight democracy

ALSO! What a CIS-gender shitlord.

Who would have thunk that I couldn’t experience art, walk through the park, or cross a bridge without the loving arms of the government?

The modern state has to encourage a cult-like worship of democracy, it’s the only way they can have any sense of legitimacy since they can’t claim the divine right of kings anymore. They’ve simply replaced it with ‘the will of the people’ until it’s no longer convenient or the people disagree with them (as we’re seeing with, say, the EU) and then they have to blame the wreckers and kulaks for misleading the proles.

I fucking hate the term, “the will of the people.” It’s a bullshit term that give credence to the Might is Right Theory of Progressive Governance.

These people have taken ‘muh roadz!’ to the farther possible limit without any irony.

What’s comical is that I’ll bet that guy completely agrees that the U.S. government should stop subsidizing Walmart’s payroll by charging a higher minimum wage.*

*Not my belief, but a common claim of progs as to why their racist policies aimed at dis-employing the vulnerable and marginalized members of society are actually for the common good.

The guy who posted this is an Obama cult member and sucks the cock of statism. When I mentioned that Obama drone warfare murdered a lot of innocent people in the Middle East and waged a war against journalists and whistle blowers, he gave a mealy mouth defense of Obama and blamed the GOP for those actions. He seriously said that it’s the GOP’s fault because they didn’t tell Obama that he shouldn’t do these things. But in the same paragraph said that the GOP were a bunch of obstructionists.

After that conversation, I made a decision to never ever talk politics with him again.

After that conversation, I made a decision to never ever talk

politicswith him again.He’s an okay and successful guy but he has a bad case of victimization. The dude drives a 2017 Lincoln, has a high paying job, a nice girlfriend, and lives in a nice place. But yet in his mind, there are sinister racist forces out there trying to destroy him. Outside of politics he’s a cool person.

Do you ever casually point out that the people keeping him down must really suck at it considering how successful he is?

Tarran, in a post a few weeks ago, you mentioned Robert LeFevre. I have been listening to his podcasts at Mises. That’s good stuff. Thanks. I listened to his origins of socialism, communism, and communal communism this morning while I was mowing. He does a very good history and is easy to listen to.

I’m glad you like it.

Reading that must be what jumping off a building must be like. The first few sentences were pure bliss. Then splat.

I wanted to comment on it but it has so many fallacies and shitty premises that it wasn’t worth my time. Each sentences would have produced at least one long ass paragraph.

A few months ago I went down the rabbit hole of taking apart each specific point of a proggie meme on the derpbook.

Long story short, I was up until midnight arguing against about 5 different people. I may have partially gotten though to one. 3 quit and another accused me of gas lighting them. I will admit, it was kinda entertaining, but thoroughly exhausting to try and talk logically with those people.

I used to do that all the time and it just got exhausting because whomever I was arguing with argued in bad faith and burned straw men like crazy.

Getting this in late, but I think something’s missing in the explanation: The 62-year-old Congress Critter is a TEA-partier. It was some retired “Spec-Ed” teacher [eye roll] who came up with the bullshit response about the greater good.

And, of course, People are eating that shit like kobayashi…

Or you could solve most of those by either having the government not exploit taxes out of people to ‘provide it’, or at least leave in the responsibility of more local and state-based governments which increases the likelihood of it actually benefiting those who pay for it. But hey, you want your maternity care pony, so fuck actual logic or efficiency.

And actually the whole point of a civil society is that it’s explicitly the voluntary actions of those in a community separate from the actions of the state, and that definition goes back to the bloody Greeks, not that I’d expect Random Internet Commenter to have read Aristotle.

the greater good

Fucking space weeaboos.

The funny thing is you don’t even need to be an anarchist to answer this question.

A bridge, a sidewalk, a library a park, etc. are general goods that can be utilized by anyone who chooses to use them and as such are general benefits to society. Maternity care ONLY benefits that specific woman/family having a baby. Not driving over that bridge or walking down that sidewalk or playing in that park is a choice I am making but I am free to change my mind and utilize those resources at any time should I desire or need to do so, there is no corresponding way in which I can benefit from your receiving free maternity care.

I am for sure not paying for that bastard 62 year-olds insulin pens!

Shorter derp:

Submit to the collective, comrade.

Yeah, my cousin posted that. I don’t talk to my cousin.

The fun part about this is how different the response would be if why should we pay for the same 62 year old man’s Viagra were called into question.

I would bet that this same moron has #RESIST!! and #NOTINMYNAME!! littered elsewhere on the intertubes.

OT : Meanwhile, in San Francisco. Sorry for the huge quote, but it’s important to illustrate my point…

I can’t believe these people are implementing a two-tiered justice system based on wealth, that this can actually happen in America. The whole point of an equal system was to avoid the tremendous moral hazard that comes from treating people differently based on their wealth and status. What in the fuck happened to this country, where we were all so proud of our equality under the law?

I also must note that the non-profit person, within the same few paragraphs, compares fines to taxation and then says that when fines are lower, revenues increase because more people pay them willingly. I guess fines and taxation are both the same and different, otherwise lowering taxes might also increase revenues.

Um, if fines aren’t impoverishing at least a little then they are not a deterrent at all

They say ‘Oh we need to charge poor people less!’ but what is really going to happen is the fines as they are now will become the minimum and they will simply jack them up for the middle class. The rich will get out of them because the lawyers they have on retainer will go to court and get them dismissed. So everyone is getting much more fucked than they used to be.

Only in America? Don’t make Sweden laugh.

Are the really that unaware that it is their progressive policies that created the tremendous disparity of wealth? You only see things that out of balance in places that have limited the supply of housing and other necessities, and taxed the residents to the point that it becomes an exclusive enclave of only the most wealthy.

I guess fines and taxation are both the same and different, otherwise lowering taxes might also increase revenues.

Schrödinger’s tax.

A tidbit from here in Tampa: http://yerridlaw.com/other-personal-injury-actions/victims-sue-ex-boss-of-workplace-killer/

In Florida you can talk all the smack you want about a former employee so long as you can back it up but don’t disclose a former employee’s “quirks” and it can mean big trouble.

ESPN hits rock bottom, busts out the gigantic Caterpillar excavator to start digging.

Who the hell is is that targeted towards?

the unemployed

I was going to say whoever is watching ESPN instead of getting ready for work, but you covered it.

So Mike and Mike was the one tolerable thing left on ESPN and they are going to kill it?

That said Golic and Wingo will probably be fun to listen to so it is not a complete loss yet

Got to the bacon and I stopped reading…sorry not sorry.

Good read up to that point sir. StL in da house.