(Go here for Part 1)

George Keith was a highly educated Scottish schoolmaster…

A Scottish schoolmaster – perhaps George Keith looked something like this

…who left the Presbyterians for the Quakers in the 1660s. He endured the persecution being laid on the Quakers at the time, but the persecution didn’t stop him from taking part in debates with his former Presbyterian coreligionists and going on a European mission trip in the 1670s with other big-shot Quakers: George Fox, William Penn, and Robert Barclay (fellow Scot and author of Quaker apologetics). It was Barclay who helped get Keith a job in North America, surveying the boundary line between the then-colonies of West Jersey and East Jersey.

At the last minute, people came to their senses and said, “wait, do we really want two New Jerseys?”

Around 1689 Keith went to the Quaker-run colony of Pennsylvania (named after William Penn’s father, Admiral William Penn). Keith served for a year as headmaster of a Quaker school. Educator by vocation and educator by nature, Keith thought that both younger and older Quakers in the colony were in need of religious instruction. Too many Quakers seemed ignorant of the basics of the Christian faith, relying on inspiration and vague spiritual ideas, and sometimes lapsing into heresy. Keith wrote a catechism to help get Quakers up to speed.

Keith also waded into polemics with members of the Quaker establishment. Rufus Jones, Quaker historian wrote: “It was quite as much the spirit as the doctrine of George Keith to which the Friends objected. He loved controversy, and in the days when he was in favour used the severe language of his time against the opponents of Quakerism.” In other words, Keith was much like other Quakers in that period, who were accustomed to using strong language against their adversaries within and without the Quaker movement.

For example, one of George Fox’s early pamphlets was called The vials of the wrath of God: poured forth upon the seat of the man of sin, and upon all professors of the world, who denieth the light of Christ which he hath enlightned every one withal, and walk contrary to it, with it they are condemned: and a warning from the Lord to all who are walking headlong to destruction in the lusts of the flesh, and deceits of the world, that they may repent and turn to the Lord, lest the overflowing scourge sweep them all into the pit.

And Jones himself notes the vituperative tone Keith’s opponents took.

Much of the impassioned debate was over theological points which we need not consider now. But part of Keith’s beef was with the Quaker elite in Pennsylvania, such as deputy governor Thomas Lloyd (Penn was in England), who ran the colony as well as serving as leading ministers in the Quaker meetings. These elites had grown lax, Keith thought, embracing wealth and worldly government responsibilities at the expense of Quakers’ pacifist principles.

A man named Babbitt, a smuggler turned pirate, stole a ship from the wharves in Philadelphia and began sailing around robbing other ships in that port city.

The magistrates, who were leading Quakers, sent a party of armed men to deal with Babbit. Apparently they chased Babbit and his men off their stolen ship. None of the pirates were killed, but apparently some were wounded. A Baptist preacher, John Holmes, wrote a satirical poem about this seeming violation of Quaker peace principles – a charge to which of course any Quaker government official was open.

The Babbitt affair soon became central to the clash between Keith and his followers, on the one hand, and the Quaker establishment, on the other. The Pennsylvania Yearly Meeting was split between a majority which supported the Quaker governing establishment, and a minority which backed Keith and his “Christian Quakers.” Keith’s supporters often had pre-existing grievances about the domineering behavior of the leading Quakers in the colony, seeing them as a bunch of rich SOBs who took power into their own hands without regard for Quaker principles. The bitter dispute between the Quaker establishment and the Keithians culminated in the establishment of rival Meetings. At one point during an argument, each group took axes to the galleries from where the other side wanted to sit.

Twenty-eight prominent Quaker leaders in the religious and political life of the colony wrote a condemnation of Keith, calling him divisive and turbulent. Keith and some of his supporters published a pamphlet in refutation called An Appeal from the Twenty Eight Judges to the Spirit of Truth and had it printed by one of Keith’s supporters, William Bradford, who happened to be the colony’s only printer and a Keith supporter. Bradford had lost his printing contract with the mainstream Quakers for supporting Keith, and though he offered, in the spirit of fairness, to print the anti-Keithians’ pamphlets, they didn’t take Bradford up on it.

While much of An Appeal went over theological issues unconnected to the Pennsylvania government, there was also a challenge to the Quaker establishment’s behavior in the Babbitt affair, posed in the form of a rhetorical question:

9. Whether the said 28 Persons had not done much better to have passed Judgment against som of their Brethren at Philadelphia (some of themselves being guilty) for countenancing & allowing some call’d Quakers, and owning them in so doing, to hire men to fight (& giving them a Commission so to do, signed by 3 Justices of the Peace, one whereof being a Preacher among them) as accordingly they did, and recover’d a Sloop, & took some Privateers by Force of Arms?

…not to mention that Quaker government officials had set a demoralizing example by giving arms to allied Indians and compromising the pacifist testimony which other Quakers were persecuted for upholding. Plus, Quaker judges administered justice, which by definition involved using violence against alleged offenders.

To Keith and his supporters, Quakers participating in violence was like…

In short, Keith didn’t believe Quakers should be government officials, since a government official’s duties included the use of force, which was contrary to the best Quaker principles. What made the mainstream Quaker establishment particularly sensitive on this point was that this sort of logic would drive Quaker officials out of office, leaving them to be replaced by non-Quaker officials in their own colony. It was a politically turbulent era (see below), and the danger of the Quakers losing control of Pennsylvania was a real source of concern. A renegade Quaker saying that Quaker magistrates had a duty to resign would not help matters.

The Pennsylvania establishment had Bradford arrested and his printing press seized, and revoked the tailor’s and victualer’s licenses of Bradford’s codefendant, one McComb, a businessman who had helped distribute the pamphlet.

Keith and some other associates were also charged, while a government proclamation denounced the “sedition” of the Keithians.

The prosecution portrayed Keith and the others as disturbers of the government because they had criticized Quaker officeholders. Keith and his codefendants, on the other hand, said that they had said nothing against the government qua government, but had denounced Quaker officials as part of a religious dispute within Quakerism (The non-Quaker officials in the government seemed to agree, since they didn’t sign on to the prosecution). The distinction was important because the right to criticize the government was not as well developed in Pennsylvania as the right to engage in religious controversy. As far as the latter was concerned, Pennsylvania had been founded based on religious-freedom principles, so the prosecution insisted that of course it wasn’t prosecuting Keith and the others for alleged theological error – that was what the Quakers’ persecutors did, and of course the Quaker establishment weren’t persecutors. They were simply clamping down on political dissent and insults to government officials.

Keith and a codefendant were convicted and fined five pounds each. Bradford had a hung jury and wasn’t retried, perhaps because Bradford hightailed it out of Pennsylvania, becoming the public printer in the colony of New York.

Keith publicized his trial in England, accusing the Quaker establishment in Pennsylvania of imitating the theocrats of Massachusetts and practicing religious persecution. Soon Keith went to England in person to set up headquarters for his “schismatic” brand of Quakerism.

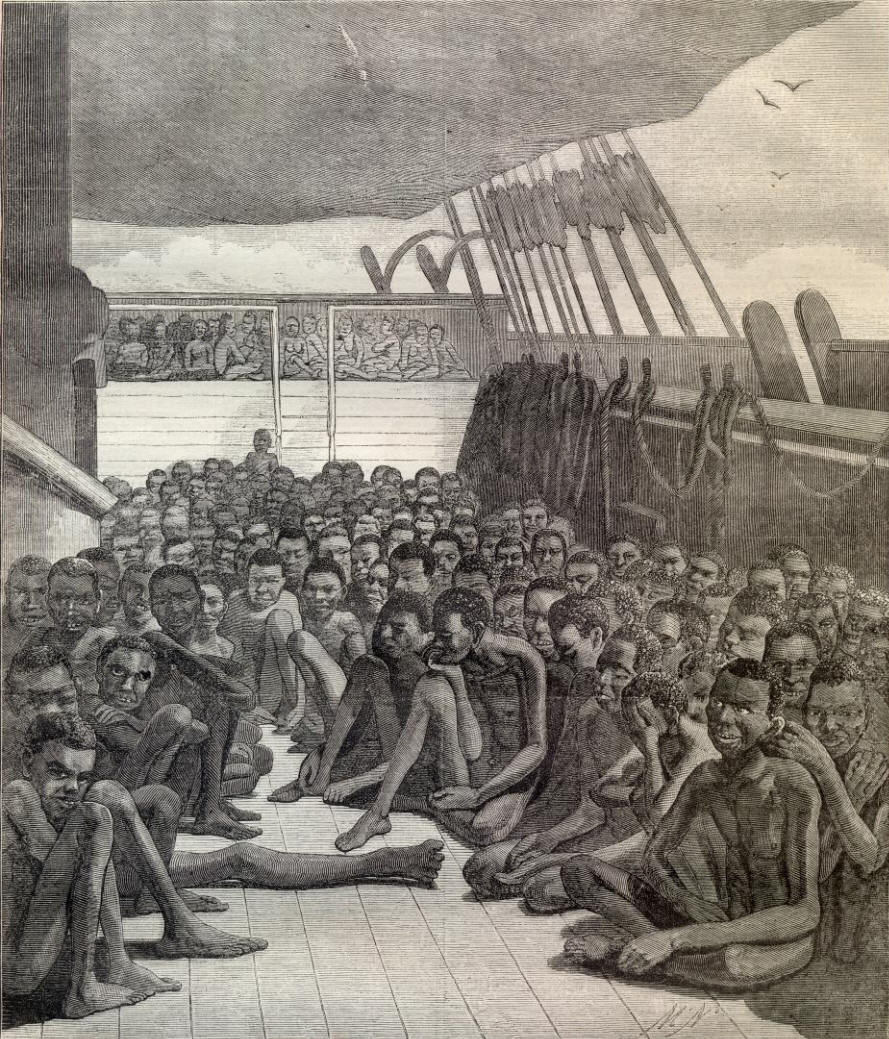

Meanwhile, Keith and other Christian Quaker leaders denounced African slavery – which was itself a nasty kind of piracy where kidnapped human beings were transported by ship to the New World: “as we are not to buy stollen Goods…no more are we to buy stollen Slaves; neither should such as have them keep them and their Posterity in perpetual Bondage and Slavery, as is usually done, to the great scandal of the Christian Profession.”

The Keithites were not the first Quakers to issue such a protest against slavery – that honor belonged to some German Quakers in Germantown, PA. The Germantown antislavery memorial of 1688 was bureaucratically sidelined by English-speaking Quaker authorities.

(The Holy Office (Inquisition) beat the Germantown Friends by two years, issuing a denunciation of the African slave trade in 1686. Illustrating the limits of the Inquisition’s power, the decree was pretty much ignored.)

Quakers were numerous in the 17th-century Caribbean, especially in Barbados and Jamaica, and they defied Barbadian ordinances by having their slaves attend worship meetings with them. This, along with refusal of militia service and tithes, led to persecution of the Caribbean Quakers, but they did not challenge the underlying legitimacy of slavery itself. Quakerism would wait until the mid-18th century before disavowing slavery and forbidding Quakers from owning slaves.

Meanwhile, what was William Penn doing about the Keithian crisis in his colony? Actually, it appeared that Pennsylvania might not be Penn’s colony any longer.

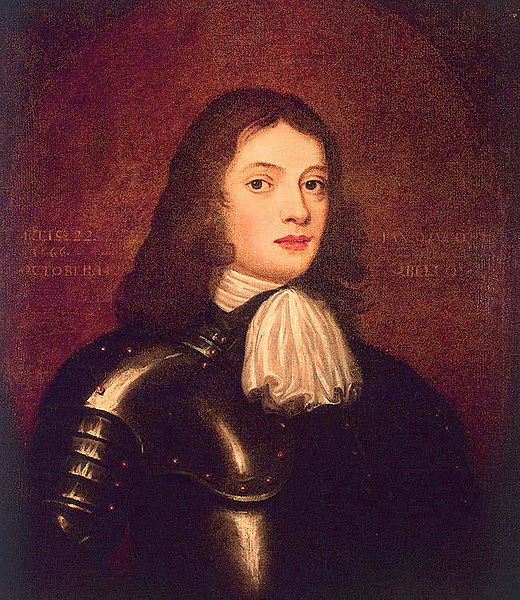

William Penn in his early twenties, before he became a Quaker – he wanted to be a soldier, but his father, Admiral Penn, vetoed the idea.

You see, back in England, Ireland and Scotland there’d been a spot of bother. King James II, the guy who’d given Penn his colony,

had been driven out of England in 1688

Plotters against James II met in the Cock & Pynot Inn, Old Whittington, now the Revolution House Museum

and replaced by William of Orange and his wife, James’ daughter Mary.

(William of Orange was also the son of James’ sister. James’s second wife, Mary of Modena, was close in age to James’ daughter Mary, and back when the two Marys were teenagers James had told his daughter that she and her new stepmother would make great “playfellow[s].”)

“Ewwwww!”

But Penn probably wasn’t brooding over inbreeding and kinky stuff in the royal houses of Europe. While others celebrated the “Glorious Revolution,” Penn was on the lam, facing treason prosecutions in England and Ireland. Treason in this case meant adhering to the losing side of the Revolution – Penn had not only gotten a province from James, he had supported some of that monarch’s controversial policies, leading to rumors that Penn was a secret Jesuit abetting the schemes of the Catholic James.

Penn kept in touch with James after the latter’s overthrow despite the fact that James was living in exile in France, with which England was now at war. To avoid arrest, Penn hid out in various places in England, surfacing briefly to attend the funeral of George Fox, founder of Quakerism, and surfacing again to give a private interview to a government official, explaining how he was totally innocent. In 1692, the new government in England took Penn’s province away from him. All this was why Penn hadn’t been able to step in and deal with the whole schism/persecution situation in Pennsylvania.

Penn was no Vicar of Bray – he didn’t pretend that he was thrilled at the change of government. But he managed to persuade the new government that he had accepted the new political situation and wasn’t conspiring with ex-King James. Or at least the government pretended to believe Penn’s story. By 1694 the treason charges had been dropped and Penn had gotten Pennsylvania back.

But now, with George Keith in England and making trouble, Quakerism itself was in danger.

As head of his own branch of Quakerism, Keith denouncing Penn for his supposed Jacobite (pro-James) sympathies. Later in the 1690s, Keith left Quakerism altogether and joined the Church of England, becoming an Anglican clergyman who focused his energy on opposing the Quakers. Apparently, it wasn’t a dealbreaker for Keith that the Anglicans were part of the proslavery establishment in the English Empire. The Keithian Quakers either drifted back into the Quaker mainstream or joined other religions.

As a newly-minted Anglican, Keith joined the high-church party, which was frustrated at the wishy-washy Anglicanism promoted by King William. Keith and the high church crowd turned their attention to cracking down on radical religious dissent. The new government had extended a limited degree of toleration to non-Anglican Protestants so long as they accepted certain basic doctrines, particularly the Trinity and the divinity of Christ. But religious troublemakers known as Socinians (Unitarians) and Deists were beginning to come out of the closet, denying basic Christian beliefs and prompting calls for their repression. Parliament would respond in 1698 with a new Blasphemy Act targeting anti-Trinitarians.

Keith and other anti-Quaker activists tried to paint the Quakers as blasphemous enemies of Trinitarianism and other basic Christian doctrines, petitioning for Quakers to be denied their rights under the Revolutionary settlement. Penn and other Quaker leaders fought off these attacks, and in fact managed to get some relief from some (not all) of the repressive laws which oppressed their coreligionists. It was helpful that the Quakers reaffirmed their loyalty by condemning a Jacobite assassination plot against William.

The actions of the pirate Babbitt had achieved quite a ripple effect throughout the Quaker world.

Works Consulted

William C. Braithwaite, The Second Period of Quakerism. London: MacMillan and Company, 1919.

Carl and Roberta Bridenbaugh, No Peace Beyond the Line: The English in the Caribbean 1624-1690. New York: Oxford University Press, 1972.

Douglas R. Burgess, Jr., The Politics of Piracy: Crime and Civil Disobedience in Colonial America. ForeEdge, 2014.

Jon Butler, “Into Pennsylvania’s Spiritual Abyss: The Rise and Fall of the Later Keithians, 1693-1703,” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 101, No. 2 (Apr., 1977), pp. 151-170.

J. William Frost (ed.), The Keithian Controversy in Early Pennsylvania. Norwood, PA: Norwood Editions, 1980.

Mary K. Geiter, “Affirmation, Assassination, and Association: The Quakers, Parliament and the Court in 1696,” Parliamentary History, Vol. 16, pt. 3 (1997), pp. 277-288.

__________, “William Penn and Jacobitism: A Smoking Gun?” Historical Research, vol. 73, no. 181 (June 2000), pp. 213-18.

David E. W. Holden, Friends Divided: Conflict and Division in the Society of Friends. Richmond, IN: Friends United Press, 1988.

“Introducing: George Keith’s An Exhortation & Caution to Friends Concerning Buying or Keeping of Negroes (New York, 1693),” https://roses.communicatingbydesign.com/history/ePubs/Keith-Exhortation_2Wintro.html

Rufus M. Jones, The Quakers in the American Colonies. London: MacMillan and Company, 1911.

Ethyn Williams Kirby, George Keith. New York: D. Appleton-Century Company, 1942.

_______________, “The Quakers’ Efforts to Secure Civil and Religious Liberty, 1660-96,” The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 7, No. 4 (Dec., 1935), pp. 401-421.

Leonard Levy, Blasphemy: Verbal Offenses Against the Sacred, from Moses to Salman Rushdie. New York: Knopf, 1993.

David Manning, “Accusations of Blasphemy in English anti-Quaker Polemic, 1660-1701,” Quaker Studies 14/1 (2009), pp. 27-56.

John A. Moretta, William Penn and the Quaker Legacy. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007.

Andrew R. Murphy, Liberty, Conscience and Toleration: The Political Thought of William Penn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Kenneth Andrew Shelton, “The way cast up: the Keithian schism in an English Enlightenment context.” PhD. Dissertation, Boston College, 2009. Online at https://dlib.bc.edu/islandora/object/bc-ir:101194/datastream/PDF/view

C. B. Vulliamy, William Penn. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934.

Maureen Waller, Ungrateful Daughters: The Stuart Princesses Who Stole Their Father’s Crown. St. Martin’s Griffin, 2004.

David L. Wykes, “The Norfolk Controversy: Quakers, Parliament and the Church of England in the 1690s,Parliamentary History 24(1) (2005), 27-40.”

Ima gonna pimp this (again) because it’s piratey and an excellent read.

The Invisible Hook: The Hidden Economics of Pirates .

Entertaining, educational, accurate and well cited.

Eddie, the best compliment I can give you it this: CNN would fire your ass.

Seconded.

It’s stuff like this that really should get crammed into an anthology. I’d certainly pay money for a tangible artifact like that.

“Being Glib for 3 years” (three years of Glibertarians.com should be sufficient to amass an anthology’s worth of stuff)

Friends? Not everyone is your friend.

https://youtu.be/2N5jF4fGs1M

Especially if they try to burn down your house.

Admiral Sir William Penn. He was knighted, Eddy.

Also, the colony was first named “New Wales”, but King Charles II changed the name to honor the elder Williams. The colony was given to Penn in order to settle a debt held by the crown to the Admiral Sir William Penn.

I’ve heard various things about the debt – Charles was known to stiff his creditors, so why this favor to one particular creditor? It’s not as if you can put the King in debtor’s prison.

Which leads some historians to think that the debt-settlement thing was tacked on to the deal, a deal which had been reached for other reasons.

…and if Charles was passionate about repaying debts, he could have cut the budgets of his mistresses and their offspring and used the funds for debt service.

Yes, the debt forgiveness was mostly to give cover to the deal and appease parliament.

The real reasons were that Charles wanted to get rid of the Quakers, and that the late admiral was a close friend, not just a normal debtor. As Massachusetts colony was rather successful at eliminating the problem of the puritans, a colony set aside for the Quakers seemed like a good diplomatic solution.

So, like Australia, only for religious fanatics instead of ordinary criminals?

In Charles II’s time, the distinction between the two would have been slight.

*looks at headlines from merry ole England*

Yeah, but we got the better end of the deal.

Pretty much. We had Georgia set up for the criminals.

Technically, Georgia wasn’t a penal colony, but it was damn close to one.

<fx: scratches head wondering why there’s so little Welsh spoken in Georgia> :p

Pennsylvania was the new Wales, and probably the reason Philadelphia is the way it is.

Georgia was for the Irish.

We have tons of them here but none speak Welsh. Loads of Irish who dont speak Gaelic. I have often wondered about that. We still have loads of people in Louisiana that speak ‘french’ but none of the other languages seem to have survived.

One notable exception: there is a community south of Krotz Springs that still speaks whatever language their Canary Islander ancestors spoke. Hat tip to Heroic Mulatto for helping me solve that mystery.

Yeah, the area west of Philly was known as the Welsh Tract.

The Welsh and the Irish already knew how to speak English, they just didn’t want to. Eventually, however, it became easier to just speakthe dominate tongue in the new world, just as it was in the old. Especially when you don’t have the extended social ties urging to use of your original language like they would have had back across the pond.

There was supposed to be a section of Pennsylvania, now mostly synonymous with Philadelphia’s Main Line, that was going to explicitly be set up for Welsh speakers, but it never worked out for a variety of reasons.

They took a wrong turn and ended up in Argentina.

Nid ydym yn bobl ddeallus.

Wasn’t expecting that answer, and I needed help translating it!

Yeah, the area west of Philly was known as the Welsh Tract.

Yup. And that’s why the Philadelphia’s ritzy suburban Main Line has towns like Bryn Mawr, Bala Cynwyd, and Berwyn.

No sheep in Georgia.

Fun fact: the first convicts England shipped overseas went to Virginia.

Australia practically only exists because the American Revolution meant that the Brits needed to find another place to ship convicts to.

Yeah, that’s a significant reason. However, recent scholarship has also determined a number of other reasons: (misplaced) fears of French expansion; need for new sources of timber for the British navy; potential naval base for protection of growing British trade with Asia.

Yes, but it’s harder to make those reasons funny, so we’ll stick to convicts. We have a reputation to maintain.

Also there were plans to ship loyalists over shortly after the Revolution but those were nixed in favour of Canada for obvious reasons.

True. But, to be fair, convicts at the time was a much broader term than we’d use today. It included bankrupts, people in debt, etc.

My understanding is that Penn pere had been allied with the Parliamentarians in the lead-up to the Commonwealth, but had been pro-Restoration, by the time Charles was returned from Holland – indeed, Penn was the captain of the ship that brought Charles back to London, which seems to be the point at which his career really took off. Perhaps Charles was very, very grateful he wasn’t ‘nudged’ into the North Sea on the passage?

Charles wasn’t from all accounts a very noble, or intelligent man, and he probably ended up as much a subject as a ruler of a ( dare I say it) cabal of powerbrokers in commerce and military. The elimination of any pretense that the King enjoyed absolute power was so new, that maybe Charles felt he needed to bolster the power he did have, with outright bribery.

Little of column A, little of column B. Charles’ rule was certainly helped by support from the powerful people in the military, and Charles liked to help powerful people in the military. Exactly where the line began is akin to finding the beginning of an ouroboros.

Charles was also very much controlled by the culture. The decision to restore the monarchy was more along the lines of “well, we’re out of ideas” rather than widespread enthusiasm. Charles was aware he needed to keep his head down and not be too vengeful lest he get turfed out too. And parliament was pretty clear on this too: they provided amnesty for a lot of those involved in the downfall of his father, and the Declaration of Breda by which he and his advisors hoped to steer clear of the problems which led to the civil wars.

This confuses me….. greatly.

This merely establishes the normative legitimacy of the narrative, shitlord.

Oh, edit fairy, I prithee, use thy Powers of Heteronormativity to change “daughter” into “son.”

On the other hand…

Fairies aren’t normally known for their powers of heteronormativity.

Dammit, hit reply accidentally.

Fairies aren’t normally known for their powers of heteronormativity, however Math fab Mathonwy may be able to help with the sex change. Some side effects may include deer, boar, and wolves.

“…Math ap Mathonwy (Math, son of Mathonwy) was a king of Gwynedd who needed to rest his feet in the lap of a virgin unless he was at war, or he would die.”

“Your Majesty, we love how you grace our Dungeons and Dragons group with your presence, but could you keep your legs to yourself, Kevin is feeling uncomfortable.”

That just screams for an anime cameo.

That’s a little different than Lloyd Alexander’s version.

I always thought the Mabinogion was interesting because I’d expected it to have had close parallels with the better known Celtic mythologies, but as I remember it, it’s a totally distinct mythic cycle.

The Brithonic Celts had a different mythos than the Gaelic Celts. Most well known Celtic myth comes from Irish or Scottish legends. The Mabinogion has more similarities to Cornish and Breton myth.

:flaps by:

Thank you, kindly fairy.

I know some of you are into linguistics, so here’s a question I have for you – why did the descendants of British colonists in some parts of the world (Australia, New Zealand, South Africa) keep something that is at least close to an English accent, while others (US, Canada) did not?

You have that backwards. The modern American accent is closer to the dominate British accent at the time of the colonies.

The American accent stayed the same, it was the rest of the world that changed.

Here’s the first decent explanation I found.

ello guvnah!

now the boston accent is confusing me.

BOSTONSTRONG

I also found this, which explains the divergence between Americans/Canucks and Aussies/Kiwis:

well, the us accent changed the second the declaration of dependence happened.

My mom did some of her graduate work on various southern accents, and (from my very fuzzy memory) she said “Appalachian English” was actually pretty darn close in patterns of speech and inflection to 17th century English. basically, that they way they talked had changed less from the original than modern british RP had

i don’t know how correct that is (i am generally skeptical of everything mom says), but i always thought it was interesting.

My understanding is that what we think of as a ‘southern’ accent is actually a morphed form of scottish, which to me makes sense when you think about it.

{Y’all} isn’t necessarily the redneck innovation that people think. There’s some strong indications that that contraction originated in England, but died out there and was retained in the American south.

One of the ‘abandoned railroads’ of English was the use of the letter ‘y’.

I’m risking the wrath of the experts here and will defer to them if they pitch in, but when people see “Ye Old Cheese Shoppe”, it’s commonly believed it’s a kind of schmaltzy faux-Anglophilia, but in original use, that would have sounded like “Thee Old Cheese Shop” – the “pe” at the end being the result of the inconsistent spelling of many nouns in English, which apparently only really died out in the late 19th century.

I think I read somewhere that the actual phonic ‘y’ is a very new innovation (comparitively) in English, and certainly wouldn’t have been in common usage in “Ye olden tymes”.

I seem to recall, one of the actual experts can correct me, but ‘Y’ was used in that context to represent the now no-longer-used English symbol ‘thorn’, pronounced like “th”. But since most type was produced in Germany at the time and the Germans didn’t have the ‘thorn’ symbol, they just used ‘Y’ instead. So “Ye Apothecary” was actually “The Apothecary”. Unless what I read somewhere was bullshit. Thorn.

It’s a shame that this thorn got past the sell-by date so quickly too.

OMWC haz a sad.

That is correct, at least as far as anyone can tell (kinda hard to ask people who’ve been dead for hundreds of years how they spoke). Icelandic still uses the letter thorn (þ) and its brother eth (ð) with their original sounds.

Thorn is my favorite archaic character.

The best explanation I’ve seen is that y was initially a substitute for þ which is how the sound* represented by “th” was written originally. The word “ye” in “ye olde” is really just “the” written funny.

* = There are actually two sounds, voiced “th” written ð and unvoiced “th” written þ — those a little more knowledgeable in phonemics will note that the word “the” uses the voiced sound, which means the use of þ is itself technically inaccurate, but it seems that English speakers stopped caring about the distinction between the two sounds before dropping the special letters for them

Getting even more into esoterics, the difference between the two kinds “th” is evident in the pronunciation of the words “theater” (unvoiced) and “thee” (voiced).

All I’m getting out of this is that English orthography had always been a cluster fuck.

We should have stuck with runes instead of forcing our bastard tongue to try and work with the Latin script.

+1 Quenya, I’d have thought.

Runes wouldn’t have fared much better. The whole language changed in pronunciation (Great Vowel Shift) which explains a good many of the quirks of English orthography. The rest largely come from borrowed foreign words which then lost their native pronunciations. Part of the reason why English orthography is unlikely to ever undergo serious reform is that it varies widely from place to place and it has never been consistent for long.

I could work with Quenya.

Doesn’t matter now. Norway can’t even agree on spelling reform, there’s no way the various versions of English could ever adopt new spellings that would actually be consistent. Hell, we can’t even get people to spell color without the stupid superfluous psuedo-French ‘u’.

All in all I consider 1066 a historical tragedy. I would very much like to see what Old Engrish would have evolved into without the level of input from Norman French. It would probably have turned out sounding rather Dutch or at worst, Frisian.

That’s interesting. Sort of related – when I was a kid, the “Tidewater” southern accent favored by the older upper class of central-to-eastern Virginia (which has mostly died out today – I rarely hear it these days) sounded very close to the stereotypical upper-class English accent. Not exactly the same, but close enough to make you think twice.

Accents are a funny thing – I never knew that a lot of people from New Orleans sound just like my Brooklyn-native grandparents did until I met a guy in the Marines who I just assumed was from NY. I had known him for almost a year before he mentioned that he was born and raised in New Orleans.

Yeah, i’ve heard what you’re talking about too, and i’ve never been clear on why that was. I suspect it is more coincidence than any shared roots.

What I’ve been told is that some neighborhoods in New Orleans had a mix of Irish, Italians and Germans that was similar to parts of NYC and thus the dialect developed along similar lines. No idea how true that is, though.

yeah, so maybe i’m wrong

i always thought it was just a coincidence that a more-aggressive and angular NO southern accent happened to sound like NY-ese when diluted somewhat.

There may be some Arcadian influence in NO accents.

Acadians

There’s many things I’d called the kiwi accent, ‘close to an English accent’, not so much.

Lupinum covered a lot of it, accent shift in England occurred based on class distinction (pretty obvious today still) and the colonial states most influenced by it are the ones colonized during that period. Kiwi is a Scot/Irish/north England blend while Australia is isolated Cockney and South African is more southern English mixed with Afrikaner. Also a lot of Canada’s initial English population were United Empire loyalists from the States which kept the accent in the same territory, at least until the Irish and Scots messed everything up.

The biggest reason, aside from regular ole drift through time and space, is that different colonies had colonists that hailed from different parts of Britain. The American Southern dialect for example, is descended from the variety of English spoken in Scotland-England borderlands. Or so I read somewhere.

David Hackett Fischer discusses some of this in Albion’s Seed.

Hence the propensity for felonious distilling when the Kings Men are absent …

I never thought about that. There’s probably quite a few shared pieces of culture that we never really acknowledge.

Along with the large number of Pennsylvanians that fled south after the whiskey rebellion. Of course, they learned from their Scottish and Irish ancestors.

Australian accents are largely the result of the predominant locale of the transportees (sorry to bring THAT up again, Ockers). I’m regularly mistaken for an Americanized Australian here in the US because my roots are in Central London – within howling distance of Covent Garden. IIRC the vast majority of the transportees were soldiers or civilians, mostly from the larger cities of England and Wales, which at the time would have been London, Swansea, Cardiff, Liverpool and Manchester. The London courts were considered to be the among the least lenient on felons, so I’d expect (no evidence available) that the majority would have been the poor, indigent slum dwellers of East-Central London (i.e. my non-Gypsy ancestors on my father’s side )

So, when I’m in my cups, I sound very similar to Alfred Doolittle of “My Fair Lady” (incidentally, the actor who played that role in the Hepburn/Harrison version, Stanley Holloway was actually Australian, and considered to have an almost naturally authentic accent). I’m not sure nowadays just how much variation there is in ‘Ocker English’, not having been there in years, but when I was in Sydney and Melbourne for a couple months in the 80’s, the accent was pretty homogeneous.

The Australian accent is pretty homogenous. The only variation that most Australians pick up on (or did in my younger days) was in South Australia which was founded by German immigrants.

One of the other complications is that English English is highly variable both in location and time.

Tolkein once commented that he could identify regional accents down to a few tens of miles. I’d go as far as to say that in some situations, it’s easy to do far better than that. And despite “BBC English” and the overall homogenization of British culture due to mobility of the population and mass media, every major city still has not only a distinct accent, but vocabulary as well. As a consequence, if you have a society largely derived from one region, at one point in time (New Zealand might qualify) you might have a ‘pure dialect’ that then has its own distinct evolutionary path,

I have to take exception to the “South Africa” claim though. SA English is heavily influenced by Afrikaans, vocabulary, phrasing and pronunciation.

To the American ear, SA English is still much closer to what you’d hear in the UK than in the US or Canada.

I work with a SA ex-pat and before I found that out, I was pretty sure he was Dutch. Doesn’t sound very UK like.

By that I mean the South Africans who are of British, not Afrikaners. The Afrikaners do sound completely different, but the “British” South Africans. They’re kind of in between an Afrikaner accent and a British accent.

Here, this is what I’m talking about. A conversation between Gary Player and Trevor Immelman.

Ah, yeah. I hear that. Not as pronounced as the ex-pat I know.

My wife, who has a low (for a woman) and clear voice just can’t be understood by southerners. Her dad is from the UP so maybe there is some barrier there, eh?

Every time Eddie posts something I have a hard time deciding which I liked more; the article or the alt-text.

OT: in way-too-early news, Champions League first qualifying round matches are being played today.

OT:

McConnell announced that the Trumpcare vote is being pushed back until after the July 4th recess. Translation: They don’t have the votes. Bill’s more or less dead.

I’d be happy, except for the fact that this means Obamacare will be with us until the end of time.

As if that wasn’t already the case. Zombie Incredible Hulk in full body armor is easier to kill than a government entitlement.

The true genius of the ACA: provide the bennies up front, get people hooked, then the massive debt comes in after Obama leaves office. At least FDR stuck around long enough to see the consequences of some of his stupidity.

If we didn’t amend the constitution, I have no doubt that Obama would have tried to stick around longer than FDR. When you plan on leaving office in a coffin, delaying the bad parts of your policies until after you’re gone doesn’t make much sense.

If there was no 22nd Amendment, then Obama would never have happened. Bill Clinton would be serving his 7th term right now.

[does math]

Crap!

Although the GOP would have an insurmountable hold on the House and Senate by now.

You mean to tell me that dictating interest rates based on a dream you had the previous night is stupid?

The Republicans really are worthless pieces of shit.

Lots of Quakers in my neighborhood in Chester County, PA. Best joke about Quaker merchants: they can buy wholesale from a Jew and sell retail to a Scotsman and still make a nice profit on the transaction.

Terrific piece. I was actually writing about the Glorious Revolution (albeit in a different context) myself this morning.

A general question for, well, pretty much anyone. I’m starting a piece that I’d like to submit. I’m seeing already that it’s starting to look a little on the longish side. Any suggestions on how to treat an overly-long article?

1. Change your name to Charles Dickens

2. Submit it for publication here in installments

3. Go on a the speaking circuit and clean up.

N.B. Only one of these steps even makes any sense, if that.

Thanks for the advice, everyone.

Well in fiction writing, it’s often said that anything not essential to the story is detrimental to it. So maybe cut some of the fat on that basis, but then again when it comes to history I find the little details help paint a more realistic image.

If there’s a natural break, you could go part 1/2/3/etc. If there isn’t a natural break, you could look for ways to divide it. Or just submit the whole thing to the whim of the editors.

If you write like Eddie, you could just remove the footnotes… 🙂

[essay converted into montage of gay porn + anime]

Well….yeah.

I think Eddie’s posts are about the limit for our attention spans. Either tighten the focus of the article, hand it to someoneto do some aggressive editing, or find a good breakpoint and split it into parts.

What is your current word count?

You could break it into multiple posts, if you like, along subheadings or natural breaks. Or post a long article and keep it from being a wall o’ text with illustrations.

Our readers, for a website, have a pretty long attention span.

tldr

*nar gz*

-_-

Any suggestions on how to treat an overly-long article?

Edit it down and pictures with funny captions.

Thanks for the advice, everyone.

/fixed

Hanlon’s Razor is backwards.

Discuss.

Assertion: It is not backwards. Stupidity is more common than evil intent.

Stupidity is more common than evil intent.

[citation needed]

I am quite sure at times it is both.

It can be both, but horses not zebras if you hear hoofbeats is usually the better bet.

I think your analogy is fine but backwards too.

Think about it this way. Not everyone is stupid, but everyone is evil at times.

I think everyone is stupid at times/about some things.

While I suppose everyone is evil at times, I think a lot of people manage to get through their day without doing anything evil.

I thought this was a pretty good article:

http://econlog.econlib.org/archives/2017/06/yudkowsky_on_my.html

Howsabout a nutpunch, as we ponder the slow-motion disaster of ObamaCare:

So far, so good, right? The parents of a sick child want an experimental treatment, his current doctors say it won’t do any good, so they say “Thanks, doc, but we’ll be signing up for the experimental treatment”, right?

Wrong. In England, apparently, you have to get permission from the state to do something like that, even in another country.

Catch that at the end? Not only do the parents have no rights to determine what treatment their child will get, they have no say on whether the NHS will actually try to keep him alive.

Just like socialist societies always end in death camps, socialized medicine always ends in death panels.

I see 3 potential refugees.

This is pretty cool. My great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather was an English Quaker who emigrated to New Jersey in the mid 1600’s. And sure enough, he went through the Caribbean first, where Quakers did not find a warm welcome.