Click here for Part One

Click here for Part Two

In both England and the United States, the legal establishment, helped by would-be reformers, first curtailed the power of grand juries to reach independent judgments, and gave grand juries the power to abuse power on behalf of prosecutors. Then the enemies of the grand jury turned around and indulged in concern-trolling about how grand juries didn’t give adequate protection to suspects. This softened up the grand jury system, making it more vulnerable to attack, and in some cases to abolishing the institution or making it optional.

Zachary Babington (1611-1688) was a functionary in Restoration England’s judiciary system. He was at various times an associate court clerk, a deputy clerk, and a justice of the peace. Zachary’s brother Matthew had been one of the chaplains to Charles I, who was killed when his royal tyranny provoked a counter-tyranny by revolutionaries. That unpleasantness was supposedly over after Charles II, son of the “martyr,” took the throne, but the new king’s supporters were on their guard to safeguard royal prerogatives and minimize the opportunities for the people to thwart the royal will. Zachary may well have learned from his pious brother about the perils of trusting the judgment of the people. So Zachary had a crack at grand juries, trying to limit their usefulness as shields for the rights of suspects. Fortunately, Zachary did not prevail at that time.

In a 1676 book, Advice to Grand Jurors in Cases of Blood, Zachary Babington complained that grand jurors often dared to ignore the judge’s instructions, and to refuse to indict suspects, or to indict suspects for manslaughter when the judge wanted a murder indictment.

A few years previously, both the Court of Common Pleas…

“Hi, it’s me again, William Penn. The judges wanted me punished for preaching in the streets, and when the jurors refused to convict, the jurors got punished, but some of the jurors fought their case in a higher court and won, and here we are…isn’t it weird how I keep turning up everywhere?”

…as well as the House of Commons had told judges they couldn’t punish jurors for making “wrong” decisions. Most pertinently for our purposes, the House of Commons had raked Chief Justice John Kelynge over the coals for his treatment of grand jurors. Don Jordan and Michael Walsh wrote that Kelynge was so biased toward suspects and defendants that he “made George Jeffr[e]ys, ‘The Hanging Judge,’ [look] like Rumpole of the Bailey.”

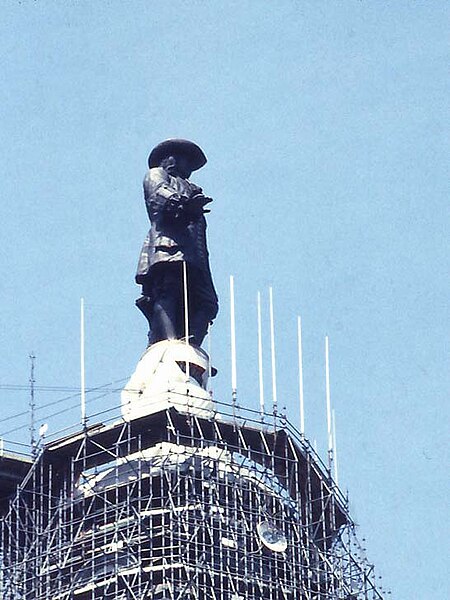

Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys presided at the Bloody Assizes, but he was still a piker next to Kelynge (not shown)

Kelynge had punished grand jurors for refusing to indict for murder in homicide cases, and the Commons warned Kelynge that he had to allow both grand jurors and trial jurors vote how they wanted, without penalty.

Babington apparently realized that, deprived of their power to punish recalcitrant grand jurors, judges could only rely on persuasion to get grand juries to fall into line. So in his Advice, Babington tried to use argument to achieve what threats and punishment had failed to do in Kelynge’s situation. Babington urged grand jurors to give the prosecution, not the suspect, the benefit of the doubt, and to err on the side of overcharging the defendant. If the defendant was innocent, or was guilty of a lesser offense, the trial jury could figure that out later. Babington specifically applied his principles to homicide cases. So long as the prosecution showed evidence that the suspect had committed a homicide, Babington said, the grand jury should indict for murder, even if there was evidence that might justify, say, a lesser charge of manslaughter. The grand jurors “are only to prepare fit matter for the Court to proceed further upon, and to make a more diligent inquiry after.” Only the trial jury can figure out the true nature of the crime after hearing “both sides” – Babington assumed the grand jury would only hear the prosecution’s side, and seemed to think that this was prejudicial…to the prosecution.

“There is very much difference in Law betwixt an Inquiry and a Trial, betwixt a Presentment and a Conviction,” said Babington, and there was a lesser standard of evidence for the grand jury’s “Presentment” – “if they find upon their Evidence, that the party said to be slain in the Indictment, by the person there charged with it, with the time, and place, and manner how, they are to enquire no farther into the nature of it.” If the charges the grand jury files turn out to be excessive, it was up to the trial jury to exonerate the defendant – “however it passeth fairly out of [the grand jurors’] hands, they may more clearly than Pilate wash their hands in Innocency from the Innocent blood of such a person.”

Pontius Pilate washes his hands to symbolize his total innocence of shedding innocent blood. (Matthew 27:24)

Babington was discussing cases of murder – then automatically a capital crime – but his reasoning would justify the grand jury in giving the prosecution the benefit of the doubt in any kind of case.

(Babington’s view of a grand jury’s functions were articulated in 2014 by, of all people, an avowed libertarian deploring the grand jury’s failure to indict police officer Darren Wilson – “the likelihood that Darren Wilson would have been acquitted if he had faced a homicide charge in connection with the death of Michael Brown does not mean he should not have been indicted….A public airing of the evidence, with ample opportunity for advocates on both sides to present and probe it, is what Brown’s family has been demanding all along….”)

Actual grand juries do not seem to have taken Babington’s Pilatian advice. While the evidence is incomplete, Professor J. S. Cockburn says “surviving gaol [jail] calenders suggest that in the seventeenth century approximately twelve per cent. of all assize bills were returned ignoramus” – that is, grand juries disagreed with the prosecutors in 12 percent of cases and refused to indict.

A colorful figure and prolific author, Henry Care, eloquently rebutted authors like Babington. Care published the book English Liberties in 1680, expressing doctrines directly contrary to Babington’s, and more in line with the real-world activities of grand jurors.

Care said that grand jurors, “if they be doubtful, or not fully satisfied” about the truth of the accusation against a suspect, should not file charges.

People may tell you; That you ought to find a Bill [of indictment] upon any probable Evidence, for ’tis but matter of Course, a Ceremony, a Business of Form, only an Accusation, the party is to come before another Jury, and there may make his Defence: But if this were all, to what purpose haye we Grand furies at all ?…Do not Flatter yourselves you of the Grand Jury are as much upon your Oaths as the Petty [trial] Jury, and the Life of the man against whom the Bill is brought, is–in your Hands…The [famous judge and legal author Edward Coke]…plainly calls the Grand Jury-men all wilfully forsworn: and Perjured, if they wrongfully find an Indictment; and if in such a Case the other Jury [trial jury] through Ignorance, &c. should find the person Guilty too, you are Guilty of his Blood as well as they: but suppose he get off there, do you think it nothing to Accuse a man upon your Oaths of horrid Crimes, your very doing of which puts him, tho never so Innocent, to Disgrace, Trouble, Damage, danger of Life, and makes him liable to Outlawry, Imprisonment, and every thing but Death itself, and that too for all you know may wrongfully be occasion’d by it, your rash Verdict gaining Credit, and giving Authority to another Jury to find him Guilty…

Care wrote that, before a grand jury can indict a suspect, the testimony must be “clear, manifest, plain and evident.” The grand jurors must “diligently inquire” into the credibility of the witnesses.

The prophet Daniel exposes the lying witnesses who falsely accused Susannah

It was Care’s defense of English liberties, not Babington’s attack on them, which became a popular work in the American colonies. Not only did Care’s English Liberties fill shelf space in colonial libraries, its content was invoked by the Patriots of the Revolutionary era in defending American liberties against British oppression. The side which cited English Liberties was the side that won the American Revolution, while the side that looked to the likes of Zachary Babington for advice was the losing side. At least for the moment.

And in both England and America, the influential eighteenth-century jurist William Blackstone came down on the side of the duty of grand jurors to protect suspects against unfounded charges.

In Blackstone’s words, grand jurors should only vote to indict “[i]f they are satisfied of the truth of the accusation.” Blackstone spoke of a “strong and two-fold barrier, of a presentment [grand-jury indictment] and a trial by jury, between the liberties of the people, and the prerogatives of the crown.” Before approving charges, at least twelve grand jurors had to be “thoroughly persuaded of the truth of an indictment” – “remote possibilities” were not enough.

While America was going through its founding era, on the other side of the Atlantic English grand juries blocked indictments in 10%-20% of cases – so for every ten suspects, one or two were cleared without the danger, expense, anxiety and humiliation of a public trial.

But the legal reformers were circling like birds of prey, waiting to enfeeble and then devour the grand jury system. Jeremy Bentham, the utilitarian legal reformer, denounced the grand jury in the eighteenth century, but added that the legal establishment wanted to keep the system: “lawyers and their dupes never speak of [the grand jury] but with rapture.”

If only that were so! In the nineteenth century, many lawyers and judges, in England and America, joined the ranks of the reformers. “Probable cause” became the standard which grand juries were told to follow in deciding whether to indict. This is certainly curious in the American case – the Bill of Rights does indeed mention “probable cause,” but that’s in the Fourth Amendment, dealing with warrants, rather than in the Fifth Amendment’s grand jury clause.

Probable cause doesn’t seem to be the same thing as believing the suspect is guilty. In fact, the concept is kind of vague. As Professor Orin Kerr put it: “In one study, 166 federal judges were asked to quantify probable cause. Their answers ranged from 10% certainty to 90% certainty, with an average of 44.52% certainty.” Perhaps that sort of vagueness is tolerable when judges or magistrates are issuing warrants, but not in the case of grand jurors accusing their fellow citizens of serious crimes.

Not only was the standard of proof watered down, but grand juries were limited in the kind of evidence they could hear. The only outside evidence they were entitled to examine was the evidence provided by the prosecutor (including private prosecutors in England – contradicting Justice Brown, English reformers said the grand jury was not an adequate protection against unjustifiable private prosecutions). Members of the public could not submit evidence to grand juries, the legal establishment made clear – not even suspects could send in affidavits and lists of witnesses with information favorable to them. Unless the grand jurors had personal knowledge of an alleged crime, they would have to rely for their information on what the prosecutor chose to spoon-feed them, and then they had to vote on the proposed indictment based on the loose “probable cause” standard, with the evidence stacked in favor of indictment by the prosecutor.

The New York judge Sol Wachtler, an opponent of grand juries who supposedly said a grand jury would indict a ham sandwich…

…had further animadversions against grand juries in his prison memoir, After the Madness. (The judge was convicted of stalking and harassing his former lover.) “If anyone should try to convince you that the grand jury is not a device used by prosecutors to garner publicity at the expense of someone still presumed innocent, watch out! The deed to the Brooklyn Bridge is probably in his back pocket.” That sort of misbehavior, of course, is the fault of the prosecutor, not of the grand jury. And somehow, even when they bypass grand juries, prosecutors find ways to generate prejudicial publicity about their cases.

Ovio C. Lewis, a law professor who served on a grand jury in Cleveland, Ohio, decided that the grand jury system was defective in comparison to the reformers’ favorite objective of a preliminary hearing before a judge. Writing in 1980, Lewis said: “In most cities where the grand jury is used it eliminates fewer than twenty percent of the cases it receives. In Cleveland, Ohio, the figure is seven percent; in the District of Columbia, twenty percent; and in Philadelphia, Pa., two to three percent.” From these figures, we see that at least some people were getting exonerated even under the watered-down grand jury system which had come to replace the robust grand jury of the founding era. It would be nice to know what those figures would be like in the case of a grand jury which fulfilled the functions described by Care and Blackstone: investigating and sifting the evidence and only indicting people whom the grand jurors are convinced are guilty.

Returning to the 19th century: some English grand juries – especially in big cities – called for their own abolition. These grand juries were influenced by presiding judges who discussed the alleged uselessness of the grand jury in front of the grand jurors themselves. The Birmingham Daily Post criticized one of these judges in 1872. Even though the newspaper agreed with the judge about the desirability of abolishing grand juries, it said it wasn’t cricket to harangue the grand jurors themselves on the subject:

The Recorder of Birmingham, in his charge the other day, made the usual remarks about the uselessness of grand juries. . . . It is unpleasant enough to have to sit in a stuffy room for two or three days, against one’s will, and it certainly does not render the infliction more tolerable to be penned up in a box, and be publicly told that one is incompetent and useless, and out of date, and in the way-nothing more in fact, than a sort of antiquated machine, less ornamental than a barrister’s wig, and less useful and important than the wheeziest of ‘criers of the Court’.

With these attitudes, it’s hardly surprising that judges and juries were making their talk of grand juries’ uselessness into a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Parliament put grand juries on hold during the First World War, as a supposed emergency measure. This simply whetted the appetite of the judicial establishment for a permanent, peacetime ban on grand juries, and such a ban was finally achieved by Act of Parliament in 1933.

Albert Lieck, chief clerk (or former chief clerk?) of London’s Bow Street Police Court, rejoiced at the abolition of the grand jury, while inadvertently suggesting reasons the institution should have been retained. Lieck acknowledged that grand juries had sometimes released suspects: “Here and there a bill [of indictment] was thrown out, but on no discoverable principle.” Perhaps the grand jurors hadn’t been satisfied of the suspects’ guilt?

Lieck uttered a non-sequitur which one would associate with Yogi Berra more than with a distinguished British bureaucrat: “the real security against oppression lies not in outworn judicial machinery [i. e., the grand jury], but in the alertness and resolution of the citizen.” Of course, grand jury service has the potential to provide citizens a vehicle to exercise their alertness toward the criminal-justice process.

American critics of the grand jury cited (and still cite) abuses which are not in any way required by the Fifth Amendment. That amendment simply says you need an accusation from a grand jury in order to be brought to trial for a sufficiently serious crime. The Fifth Amendment doesn’t say grand juries should be dependent on prosecutors for their information, or interrogate witnesses without their lawyers, or wield overbroad subpoena powers, or act in complete secrecy (unless the prosecutors chooses to leak information, of course), or fail to keep records of their proceedings. Critics have harped for a long time on these “Star Chamber” features of grand jury procedure, suggesting that the only cure is to bypass the grand jury and have magistrates or judges hold preliminary hearings, where both sides can present evidence and argue over whether probable cause exists. Then the magistrate or judge, after such an open hearing, would decide if there is probable cause to bring the suspect to trial. This type of “reform” has been adopted in England, and in many U. S. states.

The problem with such a “reform” is that it cuts the public – at least the informed portion of the public which has actually heard the evidence – out of the decision whether to bring charges against a suspect. The suspect is dragged into a public hearing by the accusation of a prosecutor, and put at the mercy of a judge who – at least in a well-publicized case – may well feel the voters – who generally don’t know the details of the case but know that the suspect is guilty – breathing down the judicial neck and demanding a trial. With the vagueness of the term “probable cause,” it wouldn’t take a whole lot of evidence for the judge to put the case down for trial, if that’s the judge’s mood at the time. Not to mention the loss of the opportunity for nullification if the defendant, while technically guilty, is morally innocent and doesn’t deserve to be dragged through a trial.

There are some useful features which were traditionally associated with American grand juries. These features are not required by the Fifth Amendment, but they provide some historical context to refute those who think the founders would have been happy to do without grand juries. Grand juries used to have (and to a greatly limited extent sometimes still have) responsibility for making recommendations relating to the problems of their communities: from fixing bad roads to dealing with polluted streams to making new laws, American grand juries have historically often broadened out from simply looking at local criminal cases.

Sometimes, and this is hard to believe nowadays, grand juries, on their own initiative, looked into corruption and misconduct by local officials, including even prosecutors and judges and cops and jailers. Sometimes grand jurors took the bit between their teeth and looked into certain types of local crime which the prosecutors and judges would just as soon not look into – maybe because the prosecutors and judges were trying to sweep that crime under the rug.

Whatever we think nowadays of these crusading, self-assertive grand juries from history – and the Fifth Amendment doesn’t require that grand juries play this role – we can reject the idea that most of the founding generation took a dismissive view of grand juries or would have been willing to abolish or sideline them, or to abolish their constitutional role in protecting suspects from overzealous or corrupt government prosecutors and judges.

The point of having two juries – a grand jury and a trial jury – is to have the grand jury make a broad inquiry, with comparatively few technical rules, in order to find the truth, and if the grand jury believes the charge, then it’s time to have the evidence heard by a trial jury under much more rigid procedural rules. For serious enough charges, it should take these two juries – one acting broadly and informally, the other following careful rules – to agree that someone is a criminal before that person can be punished as a criminal.

Now, in the real world, where most criminal charges are resolved through plea-bargaining, I’d advocate a more limited objective: To make sure that a person suspected of a serious crime has his case considered by at least one jury – and since cases are generally resolved with pleas before a trial jury can be called, that one jury would have to be the grand jury. There should be laws to prohibit plea negotiations from beginning in serious cases until after a grand jury has issued its indictment(s). We may have come full circle to the days of Henry II – grand juries are usually the only criminal juries involved in a case, and the trial procedure is almost as unreliable as in Henry’s day – a plea negotiation approaches in arbitrariness the old dunking-in-cold-water procedure when it comes to sorting out the innocent from the guilty. All the more reason to keep grand juries, so that some type of jury, at least, will review serious cases.

Is there any chance that the right to a grand jury, as intended by the Founders, will be restored any time soon? Probably not. The political and judicial establishment seems to have no particular interest in encouraging such a degree of citizen involvement. They either want to keep grand juries on a tight leash, acting on the limited evidence the prosecutors spoon-feed them, or to keep them on the sidelines, taking no role in cases unless a prosecutor needs political cover for a controversial decision.

And many regular citizens are parading around demanding that the right to a grand jury be abrogated.

And of course advocates of a restored grand jury system will be called racists.

Well, it’s too bad, but there it is.

Works Consulted

Richard L. Aynes, “Unintended Consequences of the Fourteenth Amendment and What They Tell Us About its Interpretation,” 39 Akron L. Rev. 289 (2006).

William J. Campbell, “Eliminate the Grand Jury,” 64 J. Crim. L. & Criminology 174 (1973).

Nathan T. Elliff, “Notes on the Abolition of the English Grand Jury,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Volume 29,Issue 1 (May-June) Summer 1938.

Thomas Andrew Green, Verdict According to Conscience: Perspectives on the English Criminal Trial Jury 1200-1800. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Don Jordan and Michael Walsh, The King’s Bed: Sex, Power and the Court of Charles II. London: Little, Brown, 2015.

Orin Kerr, “Why Courts Should Not Quantify Probable Cause” (March 28, 2011). The Political Heart of Criminal Procedure: Essays on Themes of William J. Stuntz (Klarman, Skeel, and Steiker, eds), pages 131-43 (2012); GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 543. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1797824

Andrew D. Leipold,”Why Grand Juries Do Not (and Cannot) Protect the Accused,” 80 Cornell L. Rev. 260 (1995). Available at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/clr/vol80/iss2/10

Ovio C. Lewis (1980) “The Grand Jury: A Critical Evaluation,” Akron Law Review: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol13/iss1/3.

Albert Lieck, “Abolition of the Grand Jury in England,” Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, Volume 25, Issue 4, November-December (Winter 1934).

Kenneth Rosenthal, “Connecticut’s New Preliminary Hearing: Perspectives on Pretrial Proceedings in Criminal Law.” University of Bridgeport Law Review, Volume 5, Number 1, 1983.

Suja A. Thomas, The Missing American Jury: Restoring the Fundamental Constitutional Role of the Criminal, Civil, and Grand Juries. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

___________, Nonincorporation: The Bill of Rights after McDonald v. Chicago, Notre Dame Law Review, Vol. 88, 2012.

Mary Turck, “It is time to abolish the grand jury system,” Al Jazeera America, January 11, 2016, http://america.aljazeera.com/opinions/2016/1/it-is-time-to-abolish-the-grand-jury-system.html

Rachel A. Van Cleave, “Viewpoint: Time to Abolish the ‘Inquisitorial’ Grand Jury System” (2014). Publications. Paper 656. http://digitalcommons.law.ggu.edu/pubs/656.

Sol Wachtler, After the Madness: A Judge’s Own Prison Memoir. New York: Random House, 1997.

_________, “Grand Juries: Wasteful and Pointless,” New York Times, Opinion, January 6, 1990, http://www.nytimes.com/1990/01/06/opinion/grand-juries-wasteful-and-pointless.html.

Richard D. Younger, The people’s panel: the Grand Jury in the United States, 1634-1941. Providence, RI: American History Research Center, Brown University Press, 1963.

“made George Jeffr[e]ys, ‘The Hanging Judge,’ [look] like Rumpole of the Bailey.”

I do say, top wit!

they may more clearly than Pilate wash their hands in Innocency from the Innocent blood of such a person.

Ummm…that’s not really a great comparison.

Huh. Seems a harmless fellow to me,

They could easily solve this by giving into the protesters and having one school for white cis people and one school for everyone else.

http://hotair.com/archives/2017/07/13/evergreen-student-school-seems-focuses-much-race-actually-becoming-racist/

So they would be separate…would they be…equal?

As long as everyone gets A’s, yes.

You know why else 1933 was a bad year for liberty?

Michael Dukakis was born?

I dunno, looks like a stalwart defender of Liberty to me!

Little known fact: In that photo he is pointing at people waiting in line at the polls on voting day.

I think he’s pointing at Willie Horton.

As promised…

http://imgur.com/a/5Y3mY

What kind of shitlord are you? Doing all this work for free? You are supposed to be squeezing profit from every possible pore (or poor).

Just getting them all on the hook with a teaser deal….

If i figure out this imagur thibg would you be kind enough to put a monocle and tophat on my Akita. As a former Columbia House member I am easily hooked

Just remember, I send out three avatars every month for ten dollars each unless you return the postcard by the date indicated.

the hook has been set!

But i get the first 10 for $.99, right. I mean, plus shipping of course

It’s beautiful, thanks Scruffy!

Wait…your hat has its own hat, that’s deep, man.

If you squint real hard, you can see a teensy top hat on the top hat on the top hat.

OT =

moar people tearing the ass out of Nancy MacLean’s “Libertarians R Koch-Funded Racist Slavers”-book

(sigh)

i’m just going to stop apologizing at this point. its just going to be a fact of life that 10-20% of my comments are mis-threaded.

I think you are a good guy Gilmore even if everyone else tbinks your a dick…

Ot. Is it worth forking out $30 for guitar strings for a relative newby guitar player?

(sigh) is that really necessary?

absolutely not. $5-10. buy ernie ball or D’addario.

e.g. 3 for $10 is a v. good deal

http://www.musiciansfriend.com/accessories/ernie-ball-2221-nickel-regular-slinky-electric-guitar-strings-3-pack

if i recall that’s what they cost back in the 1990s, so it seems like there’s been no inflation in the category

as an aside, its also generally good to pick a string gauge and brand, and stick with it permanently. i means you never have to worry about mixing sets, you’ll never screw up the intonation, and you’ll develop a very good ear for when they’re “new” versus “broken in” and “worn out”.

e.g. those yellow EB’s above are a good all around range (10-46), and are pretty much always available everywhere. lighter gauges are mostly for lead playing and will break more often if you’re just starting out.

Was just kidding. Maybe i shouldn’t kick a guy when hes down

Thks

I appreciate it. Just broke my first string yesterday so gotta get some new ones. I didnt realize the rationale for buying them like ciggarettes, pick a brand and go with them

Change your strings fairly often. Do not pay $30 for a set of strings. Gilmore is right about brand etc.

there is very little value-added in fancy-varieties or esoteric brands/styles of strings. buy the ones that are most available / most plentiful / most used. Nickel, round wound, regular gauge Ernie Balls are good enough for everyone.

the only people who use the odd-gauge matched (heavy bottom/lite top) are like chug+shred dark-metal players who need ultra low bottom plus speed riffing. flatwound strings are for hollowbody jazz guitars.

for a starting player there is absolutely no point in getting anything other than regular gauge sets.

you’ll also break them more often starting out. You’ll also pull your hair out by breaking brand new strings by spacing out and overwinding them. Get and use a tuner. also, take the time to learn how to properly wind + lock strings around the tuner post, and then ‘stretch’ them a little bit to make sure they will stay in tune.

Little things like that save you huge amounts of annoyance in the longer run. nothing is more irritating than stringing and tuning a guitar only to have one of them slip on the post and you have to start the process over again from the beginning.

I was going to say, “I’m coming begging to you, hat in hand”… but then i realized i have no hat.

If you see fit to grant me a hat, here is my avatar

http://imgur.com/a/PN1H5

but please, careful with the hair

ooooo… tough one…

How to preserve the grandeur that is the hair? Give me a minute.

I vote you mold it into a tophat shape.

Maybe it can be like the tophat that Damon Wayan’s “hated it!” character used to wear on In Living Color.

The struggle between hat and hair just permeates the atmosphere here.

Here you go….

http://imgur.com/a/ljrqN

ha!

truly, above and beyond the call of duty. i am humbled. well done.

OT: One of the things I really enjoyed from TSTSNBN was when they had the “Caption this Photo” contests. Anyone here interested in resurrecting that practice, or something of that nature?

That would be a really easy lunchtime thread starter for those days when we hit 600 comments in the morning thread.

It could be anything, too. Like the other Idea of the photoshop idea, just random screengrabs of news sites. Make up a different title.

Sports pictures where their face is doing… something.

I’d be into that.

That’s what she… wait never mind.

Anyone up for kicking Nancy MacLean around some more? The Volokh Conspiracy has just the tonic for you.

What sort of cognitive dissonance do you have to subscribe to when making these arguments, knowing how badly contextualized they are? I mean, this may be a silly or naive question, but why would you want to push a theory or belief forward when you know you have to lie to make your point?

because you believe the lie.

Common on the left to start with a cynical conclusion and then work backwards, inferring from the conclusion you’ve already reached. I think this is what passes as scholarship these days.

Sadly, that’s more “human nature” than a unique flaw of lefties.

As I say, everyone is [Insert hysterical proggy organization] about some topic.

Hmmmm, that sounds like something a Koch operative would say! That’s probably how you can afford two top hats.

you deserve credit for this as I completely mucked it up above…

…as a side note: have you read MacLean’s ‘non-response‘ to criticism? its a riot. It feels almost exactly like the Wizard shrieking ‘PAY NO ATTENTION TO THAT MAN BEHIND THE CURTAIN’

You’ve been hatted upthread

many thanks. i am flattered by the extra effort you put in.

Arizona still uses the (watered down, prosecutor’s pet version of) grand jury. Preliminary hearings are an option, but rarely used by prosecutors because it allows a defense attorney to cross examine a witness. Since the prosecutor can keep out any inconvenient facts, witnesses can testify to hearsay, and the defendant has no right to be present or cross-examine anyone, grand juries are a much faster way to get a finding of probable cause.

Our heroes in blue! Let’s everyone give them a big hand and a pat on the back!

Now, I don’t find Michael Brown to be much of a sympathetic victim but yeah, fuck these guys anyway. It’s the first I’ve seen the picture of the grinning assholes in the “I Can Breathe” shirts too.

This comment has been blessed by the Edit Fairy

oh for crissakes

Oh, ye of little faith!

The Edit Fairy (PBUH)

Fuuuuuuuuuuck.

I’ve been accused of “hating cops” before. I’m at the point where I can no longer truthfully refute that accusation.

Fuck cops.

Indeed.

I will note that someone I shared this with informed me that it’s a few years old now, but this was the first I had seen it.

That site is herpes on mobile. Your average pornsite is better behaved.

Which is a shame, since it could be a good aggregation of brutal cop news.

And here I thought the male rompers were uniquely damning of contemporary culture – little did I know that we’ve endured just as bad if not worse decades ago.

Bob Ross looks hot in that bathing suit.

I want to call photoshop shenanigans on several of these, but, considering the decade, I am just not sure.

the knit poncho is out of control

The saddest part is that I have to respond…..which one? There are TWO separate pictures of someone wearing a knit poncho.

Both of them, silly buns.

There was a time when pants were a rite of passage.

Scruffy, when the Glibs merch is available, I will personally buy you a reasonably priced item of your choice for your yeoman service in tophatting the Glibertariat.

So let it be written, so let it be done.

Sweet! Can I haz an official Glibertarian orphan doll?

If (a) it is Glibs merch and (b) it is reasonably priced, you bet. Although if they start selling inflatable orphan dolls (IYKWIMAITYD), I may have to draw the line.

Poor NDT can’t satisfy anyone.

mf’er… second blockquote was meant to close out the first 😛

/me grins, wondering how deep that nesting will go if attempted.

From the Totally Unexpected Files:

I changed up some tax planning things last year, and consequently had a pretty good refund coming from AZ. Imagine my chagrin when what I got instead was a letter telling me owed thousands of dollars. Turns out the problem was they had overlooked all the AZ withholding I had paid last year. I pointed this out to them, and a mere 3 weeks later (seriously, that’s muy rapido for taxing agencies), I get my refund check. Other than the promptish response, though, that’s not what was Totally Unexpected.

They actually paid me interest on what they owed me since the delay was their fault. That’s what was Totally Unexpected.

Interest from a government taxing agency?

Wow, that’s unusual to say the least.

In 2009 I bought a house that qualified for a tax credit from the IRS. They took several months longer than they should have to pay me the credit and paid interest on the delay. I thought it was amusing because it wasn’t even “my” money, just money that they decided to give me for buying a house.

Lots of off-topic comments, but that’s OK: That just makes the post look popular.

Eddie, I’ll be honest here – it’s a dull Friday afternoon and I simply have no desire to use my brain to read something even moderately challenging right now. Goofy off-topic links are like peanut M&Ms – terrible for you, no redeeming value, but it’s hard to stop at just one.

Ah, yes, like a Friday document dump.

There’s always MC Hamster.

Don’t be afraid. It might look long and intimidating but it’s so well-written — it’s a pleasure to read. Thanks, Eddie.

On topic thought about grand jury.

Would already being found guilty by a grand jury give a trial jury more confidence in returning a guilty verdict?

I always thought a “guilty” from a grand jury meant “we feel there is sufficient evidence that it is worth trying this case”.

Yeah, so then does a trial jury say, without properly understanding a grand jury, say “this other group of people think he did it, we concur” guilty.

I have no inclination about this.

It’s possible – it’s possible with arrests by the police, too – “the cops wouldn’t arrest the wrong person!” And it’s possible with a probable-cause determination by a judge at a preliminary hearing – “if he were innocent the judge would have let him off!”

I’m cynical enough to assume that unthinking statists sometimes get on juries, but such people would have plenty of excuses to be biased against defendants even if there wasn’t a grand jury in the picture.

I don’t want to sound glib (so to speak), but broad civic education, and an attitude of doing unto others as you’d want done to you, strikes me as the best way to back up the presumption of innocence.

This would not only apply to grand and trial jurors, but to other people in the system, like judges – who I imagine see more guilty defendants than jurors do and hence are as likely to be cynical.

There may be a problem with terminology – “grand jury” sounds somewhat…grand. I imagine (see part two) that the grand jury is “grand” because it developed earlier than the trial jury. But maybe it might work better to speak of an “accusing jury” and a “trial jury.”

The original terminology (still in use at least in some places) is “grand jury” (which issues indictments) and “petit jury” (which tries cases). No clue about the etymology.

According to these guys, “A Grand Jury derives its name from the fact that it usually has a greater number of jurors than a trial (petit) jury.”

Being roped into the criminal judicial system probably does create a self fulfilling prophecy.

They used to have defendants go to trial wearing a prison uniform – there are so many ways to signal that “here’s a guilty person and the trial is a formality.” In the last analysis, it comes down to having knowledgeable citizens as jurors and grand jurors – but of course they get *too* knowledgeable about their powers they may be excluded.

About 19 in 20 cases result in a plea bargain, so yeah.

“Lots of off-topic comments, but that’s OK: That just makes the post look popular.”

Don’t feel bad Eddie. We all get OT. In my case, it’s more understandable, since there’s usually no real topic to discuss.

mmmmm titties

I did say “usually”…

Thanks for another informative piece. Bonus points for adding the links to Part 1 and 2.

Thanks for these Eddie. Although I find them depressing as hell. That judges can so subvert the plain language of the Constitution. A system of laws and not mem. Yeah, right.