I will admit to a deep love of all things American. Whether it’s music, food, art, or literature, I love and favor the styles and practitioners of distinctly American art forms and styles. At our best, we don’t just appropriate, we blend and extend, we incorporate the experience of a country and culture that uniquely takes in and assimilates the best and strongest and produces alloys of vibrancy and depth. Only America could produce a Duke Ellington or a Mark Twain or a Grant Wood.

I will admit to a deep love of all things American. Whether it’s music, food, art, or literature, I love and favor the styles and practitioners of distinctly American art forms and styles. At our best, we don’t just appropriate, we blend and extend, we incorporate the experience of a country and culture that uniquely takes in and assimilates the best and strongest and produces alloys of vibrancy and depth. Only America could produce a Duke Ellington or a Mark Twain or a Grant Wood.

Part of the American literary alloy is the remarkable blossoming of Jewish literary art in the 20th century and the manner in which it helped shaped our common culture, rather than confining itself to a Ghetto incomprehensible to outsiders as was the case for Jewish letters in Europe or the Middle East. As usual, I’m going to be a bit self-indulgent and talk about my favorite American Jewish (lack of hyphen deliberate) writer, who would probably count as my favorite fiction writer, period. And although there’s much love for (((literati))) like Philip Roth and Saul Bellow, not to mention Ayn Rand (whom I think is highly overrated), in my mind, the quintessential American Jew writer was Bernard Malamud. Malamud did not have the prolific output of a Roth or Bellow, nor the ostentatious profundity of Rand, but what he crafted was perfectly cut and polished literary gems, where every word carried impact and meaning.

There was no contrived uplift or optimism in his work- Malamud explored the dark side of personal struggle, the difficulty of transformation, the futility of escape. Perhaps that’s why his work is becoming increasingly unfamiliar in this increasingly unserious century. And perhaps his oeuvre will be rediscovered a hundred years from now with astonishment that it was allowed to languish. I can only hope.

Malamud’s best known novels, The Fixer and The Natural were certainly brilliant and deserve the fame that they achieved. I should note that if you saw the execrable movie version of the latter, you have no idea of what the novel was about, and you need to read it- in true Hollywood style, the thrust of the book, “you can never redeem yourself” transmuted to “you can always redeem yourself,” and the wonderful surrealism of the novel is totally lost.

But in my mind, his very best novel was the semi-autobiographical and fairly obscure A New Life, whose nominal plot involves a young man with an almost stereotypical New York background moving to Oregon to take an academic position at the fictional Cascadia College, a thinly-disguised version of Oregon State. The protagonist, Sy Levin, discards (or tries to) the baggage of his life in an attempt at freedom- and that is really what the book is about, liberty and personal transformation. It is not a “Jewish” novel in any sense beyond the ethnicity of Levin- his Jewishness is incidental, not integral. And escape and transformation happen, but in ways that the protagonist (and the reader) might not expect. The ending is at once ambiguous and hopeful. This theme of transformation and liberty, to me, elevates it beyond its genre and into the ranks of great American novels. Part of the reason it spoke to me was that I first read it in my 20s, when I was an instructor at a very goyish western university, shortly after escaping the East Coast and in the process of my own transformation. I felt very much like I *was* Sy Levin; nonetheless, coming back to it later in life, the novel had lost none of its punch or power, and I was able to see things in it that had escaped me as a younger man.

Many novelists are shitty short-story writers and vice versa; Malamud was superb at both. His most famous collection of short stories, The Magic Barrel, won the National Book Award in 1959, sandwiched between John Cheever’s Wapshot Chronicles and Philip Roth’s Goodbye Columbus. But again, for me, there was better: Idiots First, from 1963. Undeservedly obscure, not even meriting its own Wikipedia entry.

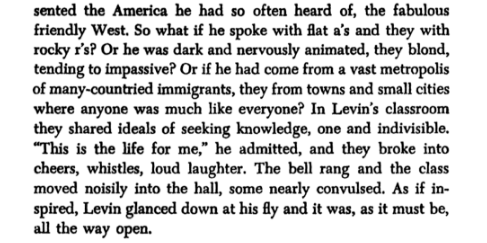

So, let me throw two samples out there which, to me, perfectly encapsulate Malamud’s brilliance and prose style. First, a short excerpt from A New Life, highlighting Malamud’s craftsman approach and delightfully bitter humor:

And a link to a short story which is more typical Malamud in theme, surrealism, and insightful depression, The Jewbird. Take ten minutes to read it, then go slit your wrists.

They had been enjoying Kingston, New York, but drove back when Mama got sick in her flat in the Bronx.

I’m sorry, but I’m going to have to call shenanigans. It’s not possible to enjoy Kingston.

not to mention Ayn Rand (whom I think is highly overrated)

Oh yeah, the several hundred Objectivists worldwide and even libertarians tend to shit on her prose are clear indicators of that.

Also, I demand a review of the supposedly “most anti-Semitic book written by a Jew” (my English teacher’s words, not mine).

I second this!

Canadian, and even worse, Quebecois, so…. non.

No, you don’t get our rich tradition of everyone hating everyone else, see, Richler was English speaking Quebecker Jew in Montreal, not Quebecois, at the time when the French Canadians got all uppity, so he spent a lot of his time shitting all over French nationalists.

Except he was right about Quebecois nationalists.

In high school our English professor took us to ‘Kravitz Town’ which was the Mile End of Montreal (roughly St. Laurent/Rachel boulevard/street) where the Jews infes – er – I mean lived and the Wops for a time and later the Porks.

That sounds like it could be its own series of articles unto itself if you just make book plural.

From there, you can go with the most racist books written by blacks before wrapping it all up with self-hating white-gentiles/Marxist works.

Oh, Christ on the Cross, really? I’m gonna have to re-visit Mordecai Richler’s stuff again?

Kill me now, God.

Ayn Rand never used one word when one hundred would do, and would have the same character give the same speech every other page.

God her writing sucks.

This past week, I attended a presentation at a medical conference on “empathetic objectivism”, which turned out to be a talk on how to show your patients empathy while remaining objective at the same time.

After the talk I approached the speaker and asked if she knew there was already such a thing as Objectivism, and it technically didn’t mean “trying to be objective”.

She was stunned. She’d also never heard of Ayn Rand. This was a mid-30s physician with multiple degrees.

“This was a mid-30s physician with multiple degrees.”

Well, there you go. The most important focus of her education was reinvented history and good progthink. I’ve met too many people like that here, working in top rated hospitals and they are extremely ignorant. And if you think this is bad, wait until we get wonderful single payer. Just be rich or fucking die in misery.

To be fair, Randian Objectivsism is not well known. Can’t really fault people for not understanding this… cult? (she was pretty weird)… from 70+ yrs ago

I wasn’t really commenting on her knowledge of Rand, or Objectivism, but the dumbed down condition of today’s college grads. They are literally completely ignorant of history and any dissenting views of the world outside of hard leftism. Which has never proven anything but a complete failure.

Sure, so I’m pointing out specifics, and you talking Platonic realities. That’s cool bro: we’re at the same place; just took different routes.

I love the ending of that excerpt.

Yeah, when Malamud goes for humor, it’s all the funnier because it’s so unexpected.

I added him to my “to buy” list. Thanks!

The excerpt was superb.

In this morning lynx’s when Negroni was asking about weddings, I had typed up a long screed of a comment about my last wedding. A small affair in a cheesy Vegas chapel where the unkempt wrinkled man doing the ceremony had his fly down the whole time. It was all we could do to not burst out laughing during the vows. We didn’t take marriage very seriously after that. Maybe that’s why it only lasted nine months.

I thought that was too tasteless to post on a thread about Negroni’s upcoming nuptials so I deleted it.

I don’t get why people don’t tell a dude his fly is open. I even tell strangers on the street, be it with a quick “Check your fly” or a “psst” followed with a hand gesture.

Xyzpdq

I think we were in shock we were actually getting married. It was not noticed until he was standing in front of us giving us the vows. At that point it was too funny to stop.

my last wedding. A small affair in a cheesy Vegas chapel

Ours as well. The Allure Wedding Chapel, right next to the muffler shop and across the street from bail bonds. We had a difficult time suppressing laughter.

I don’t remember the name of our place. That was a bunch of years ago. 1999? Maybe 98. Doesn’t matter. Did you guys stay drunk for three days on free casino cocktails and gorge on good food? That was what we did. Good times.

We got pizza, went back to our room, popped some excellent Champagne, fucked like crazed weasels, napped, and then went to see Penn and Teller. It was a pretty damn perfect weekend, other than that we were in Las Vegas (a city that neither of us cares for).

You don’t care for Vegas? How can you be a fan of America and not care for Vegas? I’m shocked. Flabby tourists clutching waffle cones. Toga wearing waitresses one step away from suicide. Desert sun and green golf courses. Controlled demolition of 70’s casinos. I love it.

Put me down as another non-fan of Vegas. There’s an annual conference held there (like so many are) and every time I’ve gone, I put comments on the exit form about holding it elsewhere. The drinking and gambling is appealing for a lot of people. For me, it’s fake gaudiness, crappy food at high prices, crappy entertainment and enough smoke to not need to buy my own (if I smoked).

Living in Vegas would be terrible. I’ll give you that. But there really isn’t any place like it on the planet. My buddies convinced me to take a trip from Germany over to see Bruges. Traditional European culture, cobble stone streets, plaza lined with cafes. Cool. Just that I had already seen that a million times in Europe. People still try dragging me to temples and shrines here and I just shake my head. Show me something new and unique. Fake gaudiness? Gaudy is best when it’s fake.

I used to be in the business. I left a job so as to not to move to Vegas. Joke was on me. I’ve been there so many times over the last 20 years it makes me want to barf.

The only time I really liked it was when we flew into Vegas, rented a car and drove straight to Utah.

My wife wants to go. I have no attraction to it whatsoever. Not into gambling. So I’ll take her and I’ll just stay drunk and stoned the entire time. Because there’s nothing else attractive there unless you want to go for the whores.

So, the Mrs. would have some kind of hang-up about that?

Vegas always makes me sad. The forced gaiety, the lack of math ability of the visitors, the desperate people with failed dreams.

Now I need a drink.

Vegas always makes me sad.

This, exactly. I have some good friends there, but we never hang out in the normal Vegas venues. I’d rather head out to Henderson and grill on the patio.

Around ’95 I stayed at Palace Station with my brother and sister in law. Same room, but I never saw it. They checked in and I sat at the BJ table putting my card counting skills to the test. You have to be nearly perfect to get the advantage, which I’m not, so I broke even. 30 hours straight. Met a rotund Korean gangster in a tracksuit that lost around 500 bucks in an hour, threatened the dealer and got manhandled out the door. Had a 50 year old lady invite me up to her suite. No, I didn’t. An 80 year old stick man threatened to kick my ass for taking the dealer’s bust card. Basically, a wonderful time.

“So, the Mrs. would have some kind of hang-up about that?”

Was that question addressed to me? It’s hard to tell in this threading. If so, not about the drunk part, the stoned part she might not like, but I don’t really care, it will be fine.

Or the whore part? Not sure, but I’m not interested. I prefer to stay STD free.

Vegas is fun for about 3 or 4 days. Unfortunately, Red Flags were two weeks at a pop. Shit gets old.

I got marred at a little white chapel in vegas that is now the Wynn parking lot. We invited our family and closest friends and most came. We had a cheesy pastor and a 80’s style porno video tape record of the ceremony. Some random Swedish tourists walking by asked my mother in law if they could watch, which she allowed. Had dinner with our guests at the house of dim sum afterwards and then went to the house of blues for drinks afterwards. 8 – 10 Irish car bombs later we went to our bridal suite and our friends each hooked up with each other. It was a blast. I can say at my wedding everybody got laid. I’m a fan of Vegas

We did the same, sort of, only in TN. It was a little more traditional, but TN being a lot closer to us and a place where we could just elope and get married same day, that was perfect.

“I got marred at a little white chapel in vegas”

John?

That entire thing sounds too much like Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

Got married at the chapel at the Flamingo. The reverend was drunk. Which is ok, because I was a little drunk too. Spent the morning in the sports book, in my tuxedo drinking, watching Ohio State win the Big 10 bball tourney. Made 300 bucks. Walked over to the chapel and started greeting friends and family. It started raining. Got married around 11:30 am. Then about 70 family and friends descended on the bar next to the sports book, and ran up a $5000 bar tab. Great Saturday.

Been married 14 years now.

Just realized I got married on a Saturday. Ohio State couldn’t have won the tourney. But they did beat MSU to get to the finals Sunday, losing to Illinois.

Guess I was drunk and nervous.

My first visit to Vegas was when I was six years old. We had a blowout overnight in the Mojave and spent half a day at the Ford dealership getting the van fixed.

It was nowhere near as glamorous as the pictures I’d seen in the World Book Encyclopedia.

Love your family-friendly avatar.

Well, that story was depressing. Give me a nice cheerful Catholic writer like F;annery O’Connor.

Flannery

a ray of hope

Mattis moves to refocus military training on ‘warfighting,’ after complaints on ‘senseless’ exercises

http://www.foxnews.com/politics/2017/07/25/mattis-moves-to-refocus-military-training-on-warfighting-after-complaints-on-senseless-exercises.html

***

Defense Secretary Jim Mattis wants to overhaul military education and training to “regain” the art of warfighting following complaints by thousands of servicemembers that their time is being wasted by hours of mandatory training, according to a new memo obtained by Fox News.

The training that is the subject of complaints covers everything from alcohol use to active shooters to sexual harassment to stress management.

…

One official with knowledge of the discussions surrounding the memo told Fox News, “servicemembers spending too much time on senseless training that is really a waste of time.” One U.S. military officer said there is “too much sexual harassment training” and not enough time spent at places like the shooting range, for example.

***

If getting rid of death by powerpoint is the only thing he accomplishes, he will be the greatest secdef in a century.

“too much sexual harassment training”

If you don’t know how to sexually harass by the time you finish boot camp, no amount of training will help.

Likewise on alcohol use.

Can he do anything to cut down the number of high-level officers?

They used to have wars for that.

“After me!”

Those were not high-level officers, Eddie.

You’re not supposed to judge during the brainstorming session.

Alright, so Duffelblog was wrong, Mattis isn’t Caesar, he’s Marius.

So maybe some of you can chime in (I might mention this in my weekly post), the firearm blog has been running a multipart piece talking about ‘overmatch’ and why it is the worst thing to ever happen to the military. Basically, people are so worried that enemy weapons might out range or out gun our own small arms that they have begun completely redesigning our military small arms to beat our opponents, without at all looking at weight or ergonomics. As a result our soldiers are carrying waay way too much weight on the battlefield which is destroying their mobility and wrecking their knees and backs.

Most of the guys I knew were incredibly envious of special forces who basically went around dressed in whatever the hell they wanted with beards. Meanwhile, they’d get on our asses if we weren’t wearing gloves and eye pro. The shit isn’t designed to make you a more effective soldier. Just one harder to kill. If it was, the best soldiers wouldn’t discard it so readily. There’s a disconnect there that I think largely stems from a military that became too sensitive to casualty numbers in Iraq and Afghanistan (or perhaps even Vietnam). The Bush administration took a lot of shit for not having the latest and best protective gear for soldiers, remember, as the media gleefully covered the rising but still relatively small number of deaths.

The weapons/ammo aren’t the heavy annoying shit for the most part unless you’re the asshole stuck with the machine gun.

+1 SAW (Squad Automatic Weapon)

That sounds like the worst job in the squad.

M240 (aka M60 gen 2) is worse than SAW – but there are slimmed down versions of both now.

Bigger/heavier – 7.62 is better than 5.56 for some purposes, but you carry a lot less ammo.

Yeah, you get a mule for that.

/former AG

Weapons and ammo/body armor are getting better. I’ve heard good things about the new helmets too, but trust me – the navy/USCG gets everyone else’s cast-offs – you should see the WWII antiques we had in the pilot house for the OOD/CO during General Quarters (straight out of the Cuban Missile Crisis).

A huge issue is lugging around those metric tons of batteries. Apparently making something shock proof means you can’t give it a rechargeable battery that fits in a tiny space. I mean, good gravy – my cell phone battery lasts days if I turn it to airplane mode. Yes, there are levels between them, but there should be some element of compatibility for electronics like that. Water is the other big issue – esp out in the desert vs temperate/jungle environments.

Much of the overmatch discussion deals with large weapons systems or strategic issues. (The fight over AK series v. M-16 isn’t going to end any time soon.) Most of the overmatch discussions are talking about Chinese missile capabilities against the US Navy and aircraft, or Russian capabilities vis a vis the defense of the Baltic states.

As a former SOF soldier I appreciated being able to wear or use the gear that was required and not what some random SGM wanted. You can make soldiers wear any protective gear you want and the casualty rate will still be above 0. Rumsfield was rightly criticized for not changing direction when his previous decisions were proved to be wrong or conditions had changed. Mistakes are inevitable fighting a war, the side that learns and changes the most effectively prevails. He didn’t and kept people like Casey in charge so we were on our way to getting thrown out of Iraq. Odierno, Gates and even Bush proved to be the people who made the changes required to change course. Did we win Iraq? I think the jury must remain out but as of now the only winner of the Iraq War is Iran.

the only winner of the Iraq War is Iran.

Also Obama. You think he would’ve been elected without Iraq? Sure, the Financial meltdown pushed him over the finish line, but it may not have come as soon if the US hadn’t spent trillions in Iraq. Alternate history, but it’s a theory anyways.

Disclaimer: I’m not infantry nor have I been in combat.

The vast majority of the combat casualties in Iraq and Afghanistan (80-90%) have been from IEDs, suicide bombs, booby traps, rockets, and mortars. So it’s silly to worry about being outmatched in a firefight.

Furthermore, most of the firefights that happen in Afghanistan and Iraq are at close range because of the terrain: it’s hard to shoot someone 300 m away in the mountains or in a city because of all the obstacles.

Finally, the small arms used by the enemy are almost always AK-47s, which under the best conditions are accurate to 380 m. The M16 is accurate to 460 m.

It’s also worth mentioning that the vast majority of rounds fired in combat are suppressive fire- you shoot in their general direction so they stay put behind cover so other soldiers can move in and actually shoot them.

The people worrying about this stuff are being silly. The only valid point they have is that the AK fires a heavier bullet which can penetrate US body armor more easily. In my view, that means it’s the armor that needs fixing.

Definitely a lot more casualties percentage-wise from IEDs, but there are still a ton from SAF – just not as many deaths comparatively speaking. If someone shoots at you, you want to be able to shoot back (lots of complex attacks too – hit an IED and then shoot them or drop some mortars on them).

Biggest issue is that plates don’t cover that much. re: some of my current work…..you’d be surprised how many different places you can get hit in the chest/shoulders/torso while wearing plates depending on your position vs shooters positions – and still die.

The next war won’t be the same as the last war.

The smart approach is to provide options. Equip troops to meet the given scenario. When conditions favor being light, be light. When they favor armoring up, armor up. Same applies to weapons.

Question Derp…are most grunts trained on multiple weapons?

When I went through basic, we qual’d on M16s. Got to fire M249, dummy rounds from the AT-4, training M203 rounds. Learned 50 cal and M240 at my unit but never qualified since I wasn’t a turret gunner – had to know basic operations though.

On my ship, everyone standing watch in port has to qualify on 9mm (except engineers), other watchstanders need M16/M500 as well – machine gun quals are generally only during deployment – when you can shoot at floating barrels without any range issues (not necessarily super accurate but good for warning shots).

I trained on the M16, M249, M67 grenade, and M203. A lucky few got to shoot the M242 machine gun.

M240 that is.

It’s ok, they’re gonna have robot Sherpas soon

Modern militaries fight third world peasants that could be charitably called ‘light infantry’, but primarily train for fighting Cold War-esque armies (although it has gotten much better in the past two decades since 9/11, but that has come with its own baggage, like everyone relying on GPS and not knowing how to read maps). It’s the great absurdity of modern conflict, using a twenty million dollar Apache with a hundred thousand dollar Hellfire missile to kill a couple guys specced out with three hundred bucks worth of equipment and no air support. Weight’s a definite problem but ‘overmatch’ is just one point in the overall equation. Basically we have to figure out what the modern military functions as, who we need to fight and how we intend do it overall.

Maybe we should look for opponents actually worth fighting.

Now, the ISIS situation is an interesting look at how things progress. If you see some of the video clips they’ve put out – starting from scratch with a 20th century technological base (including some 21st century tech like 3d printing, drones, etc), they’ve basically gotten to the point of creating assembly lines for VBIEDs and even the heavy armored ones with mounted heavy weapons. They’ve gotten into mass production of multiple variants of RPGs from scratch, weaponizing commercial drones with home-made or modified grenades, IED “belts” covering miles of territory that are literally thousands of factory produced “mines”, etc. These aren’t Warsaw Pact leftovers or castoffs – these are designs that they came up with based on “tried and true” lessons learned from OIF and cranking them out in a factory. Absolutely nuts.

I think “overmatch” could be applied to PDs around the country, too.

From what I’ve read (I’ve never been in the Armed Forces), the weapon/ammo weight isn’t the killer—though they ain’t light—it’s all the PPE and other bullshit we hang on these guys, and that they would cut off a limb before leaving behind. Stuff like IFAKs, radios, thermals/NVGs (and the gazillion batteries to power them), flat-plane displays to get the take from assorted drones and other viewing assets, etc… ad infinitum. This is very old, but see this study someone did about soldier weights in the GWOT from the early 2000s.. http://thedonovan.com/archives/modernwarriorload/ModernWarriorsCombatLoadReport.pdf

They carry a ton of shit, which means they’re a lot slower when it comes to chasing Ali through the mountains of Afghanistan. And also means they practically can’t pursue when Ali et al decides to expend a belt of PK in harassing fire from 800 meters+. But so what? You shouldn’t be killing infantry with personal weapons that far out; that’s what things like supporting arms, or platoon organic stuff like 240s, Mk-19s, or mortars are for.

Most of the overmatch jabber is to get DoD to buy another weapons system, IMHO. Further IMHO, they should hold off until all of the LSAT innovations are ready (cased telescopic ammo, 6.5 lead-free projectile with penetrator, lightened LMG, and buy lots of stuff like the new 60mm “digital mortar”) and then do it all at once. The boffins at places like AR15.com seem to think you get 90% of the way there with a free-float M4 with Geissele triggers. Save the 7.62 or .338 Lapua stuff for the DM/Scout-Sniper guys.

140lbs+ for the assistant machine gunner. Yeah baby!

If you’re on a dismounted patrol outside the range of 120mm/155mm – you’re either SOF, or an idiot using the wrong map.

They may not be out of range of arty, but they also may not be able to get permission to use the stuff. AIUI, the US armed forces operate in a zero defect command climate, and civilian (and those that plausibly resemble same) casualties count as defects. So for whatever reason, even with a TIC, the guys getting shot at may not be able to get that kind of arty or CAS support.

So I’ve heard.

Unfortunately, 90% of that shit is dictated by congress. He can’t kill it without changing the law.

But, good luck to him.

“”The training that is the subject of complaints covers everything from alcohol use to active shooters to sexual harassment to stress management”‘

Which all sounds like liability reduction bullshit. Which is weird because I didn’t think you could sue the army

Or maybe you can, but they just shoot you

It’s ass protection for those at the top and the institution so when something bad does happen, they can’t be blamed for not having it in place and who knows, maybe Pvt Snuffy didn’t get that safety brief so his immediate chain of command can be thrown under the bus for that, if not for the actual act, and since we have a scapegoat, nothing more to see here folks!

Look at the current BS every time a congressperson or senator wants to grandstand about a handful of nude pictures on in a private group on facebook or something similar. Yes, we can give those guys article 15s and some extra duty, but good gravy – wanting to start a new congressional subcommittee to deal with this *massive* issue?

No sense of proportion whatsoever given size of our military vs actual perpetrators. Giving the same training every 2 months vice annually does not actually make any greater difference. It’s not as though PVT Snuffy forgot the “no drinking and driving” lesson you gave him between Friday and Monday – he’s just a jackass.

file under: most impressive

A selection of outstanding polyglots

***

Powell Alexander Janulus (born 1939, aged 77) is a Canadian polyglot who lives in White Rock, British Columbia, and was entered into the Guinness World Records in 1985 for fluency in 42 languages.[1] To qualify, he had to pass a two-hour conversational fluency test with a native speaker of each of the 42 different languages he spoke at that time.

Giuseppe Caspar Mezzofanti (1774–1849), an Italian Cardinal, knew the following thirty-nine languages, speaking many fluently and teaching some:[78] Biblical Hebrew, Rabbinical Hebrew, Arabic, Coptic, Ancient Armenian, Modern Armenian, Persian, Turkish, Albanian, Maltese, Ancient Greek, Modern Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French, German, Swedish, Danish, Dutch, English, Illyrian, Russian, Polish, Czech, Hungarian, Chinese, Syriac, Ge’ez, Hindustani, Amharic, Gujarati, Basque, Romanian, and Algonquin.

John Bowring (1792–1872), an English political economist, traveler, writer, and the fourth governor of Hong Kong. Reputed to have known over two hundred languages, and to have had varying speaking ability in one hundred.

Emil Krebs (1867-1930) was a German polyglot and sinologist. He mastered sixty-eight languages in speech and writing, and studied 120 others.

***

Janulus was scrupulously tested not so long ago, so I believe his record. For other claimed hyperploygots, I am skeptical.

If you want to learn the most languages for the least effort, I think Indo-Aryan ones are the best. It’s a big family (Sanskrit, Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Gujarati, Punjabi…at least a dozen languages with more than 10 million speakers). The downside many of them have different writing systems.

other random thought: much like exercise, most of the benefit from studying comes from going from none at all to some. I never understood why someone would brag about not studying.

Also, for the hypers they may be counting dialects as languages. Which is not necessarily a bad thing.

What do you think about Burton, Derpy?

Most sources say he was “fluent” in 29 languages and had partial knowledge of many others. However, it is unlikely he actually spoke Latin, Greek, or Hebrew with anyone, though he could probably read some. He was only officially tested on 5 languages in the British army- Arabic and 4 other closely related languages from India.

His record has him passing various official exams in the languages. If those exams were anything like the DLPT (the current language test the US military uses) it is possible to pass it at a proficiency level far below what most people would call fluent. A passing score on the DLPT roughly means you can have simple conversations, understand the gist of news broadcasts, and understand newspaper articles. Still, by any standard, he was an impressive linguist. He produced the first English translation of The 1001 Nights from Arabic.

Many of the languages he learned came from the same family. For example, he is said to have spoken French, Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese. Anyone who has studied more than one of the those languages can tell you if you already know one, it is not that hard to learn another. Ditto for his knowledge of Hindi, Gujarati, Marathi, Sindhi, and Punjabi. Also, almost all the languages he learned are Indo-European languages.

Suppose you learned the basics of one Romance language, one Germanic Language, one Slavic language, one Semitic language, and one Indo-Aryan language.

Since there are 4 or 5 languages in each of those families, it would not be that much harder to learn those as well since you’ve done most of the work. A strong knowledge of 5 languages could with some effort become proficiency in 20 more.

Hey Derpy, how does studying multiple languages at the same time go? I thinking about your top Klingon honors as well as your presumable real language, , for your Army career.

It’s best not to study multiple languages at the same time, but if you must, studying closely related languages will be easier.

I plan on taking the DLPT in Klingon and Swahili, which I learned previously. I’m hoping to get that extra $1,000 month for being a cunning linguist.

It takes time to mentally switch over from one language to another. If I speak Swahili one day, the next day some of words will be Swahili when I try to speak Klingon.

Nice article. Thank you for sharing OMWC.

Muchas gracias.

What JB said. I particularly liked your comments on America. Also, Malamud is a depressing mofo.

I did not see that coming. Glad I was read it aloud.

Tonight’s beer. It’s OK. It was better on tap.

Looks delish

If you’re that embarrassed by your fly being open, well, you need perspective.

Dude, I go commando.

Then if you’re embarrassed by an open fly you need bigger and prettier equipment. Show that bad boy off! Be proud! He’s got a cool (((haircut)))!

You obviously didn’t grow up with a neurotic Jewish mother.

Be that as it may, perhaps we know now why samurai dress so as to avoid such embarrassment. It’s bad enough having to commit seppuku, but doing it over an unzipped fly would be embarrassing.

That’s no Samurai.

Google image search wouldn’t lie to me.

Uh, DenverJ.

That boat does not look Jaws friendly.

Insanity evidently alluring to some

http://hotair.com/archives/2017/07/25/bad-trump-derangement-syndrome-gotten-msnbc-just-reached-1-prime-time/

That’s legit terrifying.

Not that MSNBC is #1, but that it seems to be people who didn’t use to tune into cable news now switching over. That can’t end anywhere good.

Fun game – type any random three letter combination into Google, and see how often the first thing that pops up isn’t a website some government bureaucracy.

I did jfh. First was Jesus Freak Hideout then came urban dictionary which gave me just fucked hair and jerking from home.

Imagine if Jerking from Home was an internet domain like a country – it would be bigger than all the countries put together.

FFS gave me Facial Feminization Surgeon.

Well for fucks sake

Some facials can make you feel more feminine than others. Nudge, nudge.

I tell the ladies that i read a Cosmo (ha ha ha) article that said it was great for the skin; made you 20 years younger.

She replied “oh yeah? Then how come…. “

I got two computer/programming acronyms and the name of a pipe fitting, lol.

NBD, of course, stands for No BD, referring to BD Wong, who teens think is a very big deal. So, if something’s not BD, it means it’s not a big deal.

See, the problem with ya’ll is that you’re not thinking like good libertarians. I typed FFF, fucking FFF! Like a good libertarian would type. And what did I get?

FUTURE OF FREEDOM, FUCKERS!

Orthodox Jews can’t chant as well as their SJW brothers and sisters.

So Woody Allen has his own Jew Zombie army now? Or are they all on Qualuudes?

From the playlist, Up Next

Good thing I learned to use Incognito mode for glib links.

Also, I’m sad I can’t find Ephraim Kishon (Israeli satirist) in print or e-form, as I vaguely remember him describing the Orthodox Jews living in Israel in some detail, concluding with “In short, they are our Jews” or something along those lines (it was 20 years ago and in a non-English translation, but I remember I found him funny and refreshingly non-socialist).

Watching these guys – yeah, seriously, dudes?

I don’t think this has been posted yet – didn’t see it before now, but it’s the full security footage of the shooting in Jordan last fall. You can’t see how it starts from that camera but the reactions are pretty clear. Totally not a jihadi though.

Not sure if this was linked already, but… What To Do When Your Friend’s a Gay Republican

“What To Do When Your Friend’s a Gay Republican”

Umm, nothing?

Ok, that answer was for sane people.

I’d prefer the gay friend’s article, “what to do when your friend is being a whiny cunt and won’t shut up about politics they don’t understand.”

Im still curious just exactly what trump has said or done that is anti gay. other than. it being a Democrat, I have seen zero evidence of him doing anything even remotely anti gay

“diminishing rights for the arts” sounds anti-gay to me.

(actually, it sounds like total nonsense, but I wouldn’t say that aloud)

It’s about like the shit I see circulated all of the time calling the Trump administration ‘anti-science’. Really? Do they mean anti-bureaucracy? Because they don’t seem to realize that those are not the same thing.

Nothing, ever. He doesn’t have to, he’s a Republican. That’s all it takes to judge you as racist, sexist, every fucking thingist. I’m so sick of these assholes. And I’m not a Republican, but this shit offends me about as much as one can be offended.

He’s not even a Republican.

He ran on that ticket, but a Republican he is not.

Trump was a real RINO all along! :O

That’s some Sixth Sense shit right there.

I know that, damnit, but you know what I mean. To these dimwits, he’s a Republican.

Ho hum. Here we have another story where the cops raid the wrong house, shoot and kill a man through a door, and claim he pulled a gun on them. And nothing else will happen. Whoever said humanity deserves death is right. We’re a useless stain on the earth.

http://www.wmcactionnews5.com/story/35967817/officers-kill-man-with-no-active-warrants-at-wrong-house

Today is the first time I ever remember a group of co-workers standing around talking about the cops killing people. Obviously the 2 recent high profile cases, the one involving the woman from Australia, and the cops who choked the guy to death in the parking lot of Dennies. I overheard a couple of them asking the question ‘Is it safe to call the police? I’m scared, will they show up and shoot you?’. I was on my way to a meeting, but I really wanted to stop and say ‘Let me give you some good advice, DO NOT call the police. Do you think these are isolated incidents? Ignore my advice at your own peril’. When does this stop? When a US Senator’s family member gets murdered by cops? No, of course not, the family member would be a 2nd rate value to most in Congress compared to their precious cops.

If the Justine Damond case doesn’t get us there, and it probably won’t, it will never stop.

Whatever happened to just waiting for the dude the leave the house, walking up to him on the sidewalk and serving the warrant? If they can’t read a fucking address they shouldn’t be able to serve warrants at people’s homes. In my Uni days I delivered pizzas and don’t recall ever going up to the wrong address. I don’t recall anybody coming to my front door when I was home and saying, “Oh, this isn’t 123 Elm street? Sorry.” These cops are despicable and incompetent. I wouldn’t even hire them to deliver pizzas.

That’s another thing that fucking pisses me off. How many people are actually so dangerous that you have to go to their house in the middle of the night with an army to arrest them? If these cops want to play Rambo, they should get their coward fucking asses on the front lines in some actual war zone. And yes, they aren’t competent enough to deliver pizza. So why not just make them cops and give them firearms? Sounds like a brilliant idea.

You know what makes being a cop dangerous? Shooting people at the wrong house. Why? Because they’ve demonstrated that if police show up at your house, it makes more sense to assume that they’re going to shoot you than talk to you. Given that, why wouldn’t you answer the door armed, and why wouldn’t you be at, say, a heightened state of awareness.

In honor of Jewsday Tuesday, I have a story that indicates there may be some jew blood in my veins.

“That obscure moment began a classic American story of law and change. Those who put out the leaflets were convicted of sedition. They appealed to the Supreme Court, and lost. But there was a powerful dissent by Justice Holmes: a dissent that eventually, decades later, led the Court to redefine the Constitution and American freedom.”

“Three anarchists and a socialist were in the Supreme Court case, Abrams v. United States: Jacob Abrams, Hyman Lachowsky, Samuel Lipman and Mollie Steimer. All had come to this country from Czarist Russia, fleeing its tyranny and pogroms.”

http://www.nytimes.com/1987/12/31/opinion/abroad-at-home-freedom-to-disagree.html

Shit, missed the link

I’ve always found Abrams weird, because it came only a few months after Schenck, where Justice Holmes gave us the stupid “fire in a crowded theater” metaphor that people are still using as reasoning to suppress speech a century later.

According to this, he changed his mind when his prog buddies lobbied him and told him how they were threatened with being fired from their university jobs.

I wonder if I should walk around my neighborhood and interview Jews on the street for Glibertarians.

Me: Hi, have you ever heard of Glibertarians? It’s a libertarian site ran by some Jews and well, some gentiles.

Them: What? No, I never… are you Jewish?

Me: No, I’m just one of the gentile hedonist regulars who enjoys the stories about the Jewish people. Man you guys know how to party, am I right!?

Them: *look at me like like I’m insane*

Me: Hey, here’s the URL, it’s a certified family friendly site!

I wonder if that family-friendly certification site is like those “academic journals” which let you publish stuff about mitochlorians.

I’m going to have to compare it with a slogan I’ve heard somewhere ‘The Most Trusted Name in News’. It’s like that.

Another proof that cops have always sucked, Hyman Lachowsky, a person with my namesake, was beaten to death by the police in his time in prison.

I like this place because I often see things written here that express how I feel better than I can. This is one of those times. Thanks to OMWC and to everyone else who has spoken for me without knowing you were doing so.

(Yes, I am a little bit drunk. But that should not detract from the sentiment. In fact, it’s one of those moments of pure, drunken honesty.)

(Shut up)

Hear, hear.

(I’m absolutely pissed)

(Sentiment is nonetheless sincere)

Agreed, Brilliant expression of a sentiment I completely share.

Damn, it’s not even 1PM. What is wrong with you guys? Do any of you work or do you just sleep all night and day too?

random thought

I don’t think the phrase “moderate Islam” is particularly useful. Instead, we should talk about mainstream Islam, what the majority/plurality of Muslims believe and practice.

Here is my summary of mainstream Islam:

-They oppose drugs, pornography, premarital sex, adultery, homosexuality, abortion, and birth control, while not necessarily wanting to criminalize them.

-They also oppose blasphemy and apostasy, while again not necessarily wanting to criminalize them.

-They eat halal food, go to mosque, pray, give to charity, fast for Ramadan and expect other Muslims to do the same.

-They mostly oppose the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and Israeli actions against Palestinians, but also condemn corrupt Muslim govts and terrorist groups

-They would prefer marriage and inheritance disputes to be handled by sharia courts.

-They put a high value on education, honor, and family/tribe. The group is more important than the individual.

-They regard change with suspicion and prefer familiar traditions, though they are open to using new technology.

So long story short, there are many areas of strong disagreement, but it is a mistake to classify them as enemies.

I think the best thing is to emphasize that the main victims of terrorism are other Muslims and cooperation with the US offers the best chance of defeating them.

Or just stay out of the mess entirely. That would also help.

“Or just stay out of the mess entirely. That would also help.”

Ding ding ding! We have a winner!

“The group is more important than the individual.”

So, they are basically Democrats. That right there, that is what you call a problem.

Most of the people around the world are far more conservative (socially), authoritarian, and collectivist than Americans.

In other news, most countries are corrupt, dirt poor, socialist shit holes.

Yup.

K

That’s not “mainstream” though.

Sharia law is supported, that includes severe punishments for apostasy.

http://www.pewforum.org/2013/04/30/the-worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-overview/

That’s not “mainstream” though.

http://www.pewforum.org/2013/04/30/the-worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-overview/

That’s not “mainstream.”

http://www.pewforum.org/2013/04/30/the-worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-overview/

Are you talking mainstream Islam in the US or mainstream islam *anywhere* else in the world. “Not necessarily wanting to criminalize apostasy, blasphemy, etc…”

See Pakistan, Indonesia, etc – moderates – “blasphemy” is a good way to get fired, recalled, imprisoned (prob. death penalty) – if the mob doesn’t get you first. Ditto apostasy – which of course does get the death penalty via the koran.

Or….maybe rape….that’s right, if you’re a woman and get raped, you’ll probably be the one imprisoned.

I’m too lazy to go digging through Robert Spencer’s annotated Koran again, but Aydin did a nice compilation a few months ago.

Also google “To Our Great Detriment” by Stephen Coughlin.

Yeah, that’s not “mainstream.”

http://www.pewforum.org/2013/04/30/the-worlds-muslims-religion-politics-society-overview/

So, I guess OCare repeal and replace got shot down last night? After Pence had to break a 50-50 tie to get debate on the bill to the floor? I guess you can add Cotton and Lee to Ken Shultz’s shit list.

How hard is it to just send a repeal bill to the floor? Then worry about fixing problems with a subsequent bill?