In Part One, we followed the adventures of a pacifist Quaker sailor captured by pirates.

In Part Two, we saw the Quakers, helped by William Penn, defeat an attempt by their religious opponents in the 1790s to have them prosecuted as blasphemers.

But by the late 1690s, William Penn was no longer feeling his oats.

He wasn’t getting any younger, he wasn’t getting the revenue he had expected from being Proprietor of Pennsylvania, and his finances were in a bad condition thanks to his un-thrifty, un-Quakerly spending habits. Worst of all, Gulielma, his beloved wife of twenty-two years, had died in 1694.

“As for man, his days are as grass: as a flower of the field, so he flourisheth. For the wind passeth over it, and it is gone; and the place thereof shall know it no more.” – Psalm 103, 15-16 (KJV)

But there was no time for Penn to sit around feeling sorry for himself….

The Board of Trade, the bureaucracy which oversaw the English Empire, had been receiving complaints that England’s Caribbean and North American colonies were tolerating pirates, with Pennsylvania among the worst of the lot. Other complaints about Pennsylvanians were that they were buying and selling goods without regard to the arbitrary British trade restrictions – this voluntary commerce in honest goods was to British imperial authorities about as much of a sin as trafficking in stolen pirate goods. Plus the antiwar views of the colonists meant the Empire wasn’t getting a lot of help from Pennsylvanians in the struggle with France.

As far as the Board of Trade was concerned, the worst of the pirates was Henry Every.

Every led a mutiny and took over an English ship in Spain. Renaming the ship the Fancy, Every sought plunder in the Indian Ocean, the latest popular destination for greedy sea-robbers. These East Indies pirates were based in what is now called the Ile Ste Marie off the east coast of Madagascar. From this island the pirates sailed forth against the richly-loaded ships which carried goods and treasure from the Orient.

Every left a message to English and Dutch merchants in the area telling them simply to identify their nationality and they would not be harmed. Like other East Indian pirates, Every targeted ships from the Muslim countries in the area (and would be happy to seize French or Spanish ships too). The Barbary Pirates who enslaved Europeans were Muslim. The Turkish armies which had jihaded their way through Europe, almost to Vienna, were Muslim. So there was a convenient conflation between the hostile Muslim powers near Europe and the not-yet-hostile Muslim powers with their tempting loot in the Indian Ocean.

Every’s Fancy came across the Ganj-i-Sawai, a ship belonging to the powerful Mughal Emperor in India, a potentate named Aurengzeb. The Ganj-i-Sawai was part of a fleet which was returning from a Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca with many distinguished passengers and a prodigious amount of treasure.

Every and his men captured the ship, stole the treasure and – if we are to believe the Mughal accounts and some of the pirates who later turned states’ evidence – raped the women. Every supposedly married Aurengzeb’s granddaughter, who had been on the captured ship, and she allegedly became a pirate queen.

The problem was that Aurengzeb was not someone the English wanted to cross – England’s East India Company was beginning its penetration of the Indian subcontinent, but Aurengzeb might put a stop to that if he became angry. At the time Aurengzeb was regarded as very harsh and cruel, though recent historical revisionism suggests he wasn’t that bad (for example, “Aurangzeb protected more Hindu temples than he destroyed”). But it was unwise to provoke the Emperor’s wrath, and Aurangzeb was wrathful that ships from a supposedly friendly power had committed such aggression on his pilgrim ship. What are you going to do about it, he asked the English threateningly, as he commenced retaliating.

Apologizing for the incident,

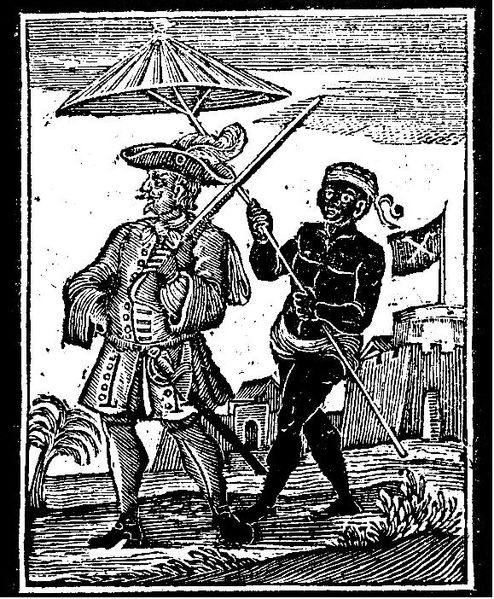

Here are the English apologizing to Aurangzeb on an earlier occasion

…the English tried to repair the damage by hunting for Every and his crew.

Several of Every’s crew members were captured in Ireland, brought to London, convicted and hanged. Based on the trial and on the confessions of the captured pirates, authorities in London got a great deal of information about the friendly reception which England’s North American and Caribbean colonies gave to Every and other pirates. Reports came in of Every’s former shipmates spending and selling their loot in the colonies, bribing officials, and even settling down and becoming respectable citizens. The Board of Trade believed that Every and the remainder of his crew might be hiding out in America.

Many people in English America were indeed friendly with the East India pirates. Many in the colonies, including many colonial officials, had personal memories of slavery at the hands of the Muslim Barbary Pirates, slavery from which they had had to be ransomed at heavy prices after enduring painful and arduous labor. The East Indies pirates were simply robbing Muslims – who were cut from the same cloth as the Barbary Pirates, the colonists thought. Speaking of cloth, calico, an Indian fabric, was very much the rage at the time, and the pirates brought calico to enliven the wardrobes even of the Boston Puritans. The stolen goods were a great stimulus to local, currency-starved economies in America.

Reports from Rhode Island, New Jersey and Pennsylvania were particularly disturbing, at least to those willing to believe ill of the Quakers – and many English officials were willing. Tiny Rhode Island had a large measure of self-government, and the rich Quakers who ruled the colony enthusiastically cooperated with the East India pirates. New Jersey, with a heavy Quaker influence, had similar problems. Of course, the non-Quaker colonies, such as New York, Massachusetts, and the Bahamas, also provoked complaints, and these places were not Quaker-run.

In Pennsylvania, Every’s former crew members were selling their loot and settling in that colony, like elsewhere in English America. As deputy governor of Pennsylvania, William Markham, a non-Quaker cousin of Penn’s, was responsible for wielding Penn’s powers while Penn was away in England. Markham had been in the British Navy and had taken part in a naval attack on Algiers, the Muslim pirate-state which Markham may have equated, through guilty by association, with the Muslim kingdoms of India.

Like other American governors, Markham gave commissions to pirates for the ostensible purpose of fighting the French, who were at war with England at the time. The commissions often spoke vaguely about “the King’s enemies,” implying that the French were not the only targets. In any case, the newly-commissioned “privateers” (a term which was beginning to evolve to describe government-sanctioned pirates who fought the government’s wars) went straight to the East Indies and preyed on Muslim shipping while making the French (who didn’t have as much seizable booty) a secondary priority at best.

Markham praised the friendliness of the pirates and the stimulus they gave to the local economy. They also seem to have brought many gifts to Markham, gifts he accepted in pretended ignorance of the givers’ piratical origins. Markham accumulated a collection of East India luxuries Although Markham arrested some of Every’s crew under pressure from London, these prisoners somehow managed to get bailed out or to simply escape. A royal official investigating Pennsylvania affairs suggested that the King wouldn’t act to suppress a rebellion against Markham, if one should develop (hint, hint). The governor of Maryland tried to stir up just such a rebellion in order to add Pennsylvania to Maryland, though that didn’t work.

A Red Sea pirate named James Brown…

Come here mama…and dig this crazy scene / He’s not too fancy…but he has loot from the Red Sea / He ain’t no drag. / Papa’s got a bunch of swag

…sailed into Philadelphia with his ill-gotten treasure, and went to see Markham, presumably with a view toward making some gifts. Brown explained to Markham about his activities, admitting that he’d sailed with the pirate Thomas Wake and also with Every, but in the latter case only as a passenger, Brown insisted. This was probably a cover story – I don’t know if Every even offered passenger service. Of the voluntary kind, that is.

Markham’s daughter fell in love with Brown and the she married the buccaneer.

Perhaps this video will give some idea of the wedding ceremony. William Penn, however, probably did not feel good about having a pirate in the family. James Brown settled on a farm in what is now Delaware, then part of Pennsylvania.

Penn had to balance the demands of the imperial authorities and those of his people in Pennsylvania. In 1696, Parliament passed a law increasing royal power over the colonies, including Pennsylvania, partly in the name of getting tough on piracy. Penn feared the loss of self-government and even trial by jury. Penn tried to explain to London authorities that Pennsylvanians had moved to their colony “to have more and not less freedom than at home.”

The colonial legislature of Pennsylvania shared Penn’s concerns to an extreme degree. The Pennsylvania Quakers, as Penn had pointed out, had a longstanding suspicion of the English government, which had oppressed them when they lived in England, would seize on any excuse to extend its persecuting arm across the Atlantic. Even the anti-piracy crusade might be a pretext for colonial officials to mistreat Pennsylvanians. Robert Quarry, the admiralty judge sent to Pennsylvania to crack down on piracy, had been removed from the governorship of South Carolina for collaboration with pirates. Now Quarry had commercial interests in Pennsylvania, which suspicious Pennsylvania officials believed would give him an incentive to use his official powers to harass rival merchants – all in the name of law and order. Quarry catechized Quaker meetings about the religious beliefs, which would have reinforced the suspicion that the anti-piracy crusade was another step in England’s long-term persecution of Quakers.

But Quarry had his own complaints:

All the persons that I have employed in searching for and apprehending these pirates, are abused and affronted and called enemies to the country, for disturbing and hindering honest met, as they are pleased to call the pirates, from bringing their money and settling amongst them.

The Pennsylvania lawmakers made an “anti-piracy” law full of loopholes to shield pirates’ local accomplices. James Brown, Governor Markham’s son-in-law was elected to the legislature but didn’t show up; when he did, he suggested he hadn’t want to risk arrest for piracy. The legislature expelled Brown and Markham acted to arrest his son-in-law, while also helping him out with bail money.

Penn came to his colony to in 1799 (bringing his second wife Hannah with him), to preside over the government in person and address the vehement complaints of the colonial officials in London. He wanted to protect Pennsylvania’s autonomy as far as he could, but he also wanted to check the unrealistic defiance of the locals against the empire. If Pennsylvanians believed themselves put-upon now, how would they like it if London took the proprietorship away from Penn (again) and administered the colony directly, removing the buffer Penn provided between his colonists and the wrath of hostile imperial bureaucrats?

Investigating the situation, Penn found that, indeed, former pirates had settled in the colony, including his cousin William Markham’s son-in-law. Penn replaced Markham and other colonial officials who had buddied up too closely to the pirates.

After Penn gave the colonial legislators a stern talking to…

WILLIAM PENN SPEAKS TO YOU, HIS BROTHERS AND SISTERS. STOP DOING BUSINESS WITH PIRATES, AND IN GENERAL, PAY MORE RESPECT TO MY AUTHORITY AS PROPRIETOR OF THIS COLONY.

…the solons repealed their defendant-friendly piracy law. Mellowing somewhat, Penn suggested that the reformed pirates who had settled in Pennsylvania be left alone, so long as they earned an honest living far from the ports and coastal areas, where they might be tempted (or tempt others) into piratical ways. Perhaps Penn was thinking of his in-law, James Brown, the pirate-turned-farmer.

Penn left Pennsylvania in 1701, and never returned.

The Board of Trade was not placated, continuing to see the North American and Caribbean colonies as refuges for pirates. The problem, the bureaucrats concluded, was that not all the colonies were governed directly by the Crown. So the Board prepared a bill for Parliament by which the proprietary colonies (like Pennsylvania) and those colonies which were self-governing based on royal charters (such as Massachusetts) would become directly ruled from London Also, the colonies would be merged into larger megacolonies – for instance, Pennsylvania would be merged with Maryland and New Jersey (PenJeryland?).

A bill matching some of the Board’s ideas was introduced in the House of Lords. To opponents of the bill, such as Penn, this was sheer oppression, abrogating charter rights. And anyway, New York was a crown colony but its former governor, Fletcher, had been in cahoots with the pirates nonetheless (Fletcher had spent time as governor of Pennsylvania when Penn had been deprived of his proprietorship). The Quakers and other colonial agents out-lobbied the Board of Trade. Penn defended his powers as proprietor in terms their Lordships could understand: “Powers are as much Property as Soil; and

this is plain to all who have Lordships or Mannours [manors] in England… .” The bill died in Parliament – but not before passing a second reading in the House of Lords. The Board kept pushing for its pet bill, but without success.

There wasn’t a major crackdown on piracy in the colonies until the pirates began relocating their predatory activities to the vicinity of the colonies themselves, as opposed to the remote Indian Ocean. Then the colonists bestirred themselves, and some serious pirate hangings began, putting an end to what some call the Golden Age of Piracy.

Works Consulted

William C. Braithwaite, The Second Period of Quakerism. London: MacMillan and Company, 1919.

Douglas R. Burgess, Jr., The Politics of Piracy: Crime and Civil Disobedience in Colonial America. ForeEdge, 2014.

Leonidas Dodson, “Pennsylvania Through the Eyes of a Royal Governor,” Pennsylvania History,Vol. 3, No. 2 (April, 1936), pp. 89-97.

Mark G. Hanna, Pirate Nests and the Rise of the British Empire, 1570-1740. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Rufus M. Jones, The Quakers in the American Colonies. London: MacMillan and Company, 1911.

John A. Moretta, William Penn and the Quaker Legacy. New York: Pearson Longman, 2007.

Andrew R. Murphy, Liberty, Conscience and Toleration: The Political Thought of William Penn. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

P. Bradley Nutting, “The Madagascar Connection: Parliament and Piracy, 1690-1701,” The American Journal of Legal History, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jul., 1978), pp. 202-215.

I. K. Steele, “The Board of Trade, The Quakers, and Resumption of Colonial Charters, 1699-1702,” The William and Mary Quarterly,Vol. 23, No. 4 (Oct., 1966), pp. 596-619.

Alexander Tabarrok, “The Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of Privateers,” The Independent Review, v., XI, n. 3, Winter 2007, pp. 565-577.

C. E. Vulliamy, William Penn. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1934.

Wait a minute, that picture can’t be correct, that guy doesn’t look anything like Wilfred Brimley.

The diabeetus got him.

It’s been fun reading about pirate history while Mr. Riven plays through Uncharted 4 again, and that’s really saying something. I think history is often the most boring thing evar.

Pirate history is often not boring at all. From the little that I have read, pirates seem to be the first hardcore libertarians willing to actually fight and die for an AnCap society.

It kind of fell by the wayside as the series went on, but the early episodes of Black Sails had rather fascinating glimpses of the way pirate ships were run and the politics involved.

PirateHistory is not boring at all.History Class has given History a bad name.

This is true. My knowledge of history was mostly through self-education.

Perhaps this is where history has failed me. Years of memorization and regurgitation of boring and mundane facts in the school system vs reading for pleasure on topics that are personally interesting.

Pirates are definitely up there on the personally interesting metric.

That’s a failure of the school system, not history, and it’s been a pretty consistent one recently. Elementary schools just don’t know how to teach it anymore. I think a much broader look at Western and classical history in general would be a lot more beneficial than the nationalist crap (which tends to focus on some boring as hell subjects for no reason other than MURICA or CANANADA) that tends to get shoved nowadays.

the nationalist crap (which tends to focus on some boring as hell subjects for no reason other than MURICA or CANANADA) that tends to get shoved nowadays.

I don’t think it’s even the subject matter. Just bad teaching. If you start from the premise that history is how we got where we are, history is very interesting.

I don’t think it’s even the subject matter. Just bad teaching.

I once at a class that was half dedicated to wheat farming. Because Canada. Yesterday OMWC and others talked about how their history teachers would prop up some nobody out of a sense of diversity. The material is part of the problem.

Crispus Attucks is a very common one. I remember them harping about him like he was about to discover a cure for cancer before the reds cut him down.

Parts of history can be very good reads, but there are lots and lots of very boring people that have books written about them due to their last names.

I pimped it before, I’ll pimp it again.

“The Invisible Hook”.

Pirate economics. Fun, easy read.

That sounds excellent. I shall have to look for it.

As shall I.

AssCreed 4 The Black Flag is pretty good on pirate history, modulo AssCreed shit (ancient aliens! Templar conspiracy!) and it’s great when it’s not an AssCreed game. If you’re curious about what happened right after the period Eddie covered above, I highly recommend it.

Also, the modern-day parts are set in basically UbiSoft Montreal as they are developing AssCreed 4, so there’s a ton of notes from management to developers that have to have been made during the actual develpoment.

AssCreed Syndicate, however, is full of shit. Not only on the timeline, but also all the bullshit socialist (evul capitalism!) overtones. Every time I do a “free the children” side mission… after the game encourages me to murder the factory managers, I say “go, children, go and starve to death! Back to the wonderland of squalor for you!”

Wait, is there no “Your work for me now, boys!” option? As a leader of a goddamn street gang would?

Fuck AssCreed, there’s a reason 4 was the only one I ever played! 1-3 were hilarious to watch someone else play and laugh at.

The structure of every one of those games pissed me off. Never made it all the way through one.

Anyway, from what I’ve read the kind of piracy exemplified in popular imagination as “the Golden Age of Piracy” in the southern Atlantic and Caribbean was actually a pretty short time, maybe 20 years or so in the early 18th Century.

OT: Pointless manufactured controversy or partisan sniping opportunity? Yes. #ThanksNorthKorea for your gigantic fuzzy harmless slave gulag. #Happy4th

Oh, it’s so adorable when leftists pretend they are such red-blooded, patriotic types who love the military.

It’s especially retarded because it’s not like military personnel don’t have some of the darkest and inappropriate senses of humour ever.

This is true. It’s why I always laugh when someone at work apologizes for saying something that’s supposed to be inappropriate or offensive – it’s almost impossible to offend or insult me.

Wow. Assholes. Assholes.

I’m checking my records… Yep. I’ve protected more Hindu temples than I’ve destroyed too! I knew I was a good guy.

Nice try, but I bet you’ve only protected the same number of Hindu temples that you’ve destroyed.

In both cases it’s zero for me.

I have visited many a Hindu Temple – during such times they have enjoyed my benevolent protection.

i have my explosives ready but I don’t think there a Hindu temple in Bucharest. Can I just blow up an indian restaurant?

Alt-right!

Can I just blow up an indian restaurant?

Good God, no! Those places actually impart flavour to food!

Yarrr.

Has anyone ever told you that your avatar could be mistaken for an American flag?

What could be more American than bacon, as long as it isn’t those over-glorified ham slices the canadians dare to call bacon.

THIS. There’s a real name for it. It’s called HAM. You’re eating HAM. Pour some maple syrup on it and chow down, but call it by its’ correct name.

How about you spell the Queen’s English properly and we’ll return the favour.

Every time you make this argument I am reminded of this.

It’s not an argument, you people talk like a fag and your shit’s all retarded.

No, because I’m a citizen and not a subject of the Empire. I spell American just fine, TYVM.

Ah, but the Commonwealth owns the language. We call the shots as the successors to the Empire. If you wish to create a series of imaginative grunts and bellows and call it ‘American’ we will be happy to let the issue drop.

Nobody owns English. That is why the language is so beautiful.

That’s just the typical excuse of the pirate, no one owns information man *tokes*.

Not going to cut it. We have our branding to think of.

I don’t think I will ever understand the whole Queen fetish. Now I need to gets me the newest National Enquirer to see if there’s any new updates on baby Princess Charlotte and Prince George the toddler!

She’s a noble old lady who has kept out of our business and is basically the best Head of State on the planet. That’s basically it.

My dad taught me to spell. I still write colour and whatnot sometimes. not as often on the computer.

You’re a good man DOOMco, I like you, that’s why I’m going to kill you last.

I had a teacher in elementary school who hated me for it.

America’s horrible xenophobia and oppression continues.

What I find hilarious is that many English find it easier to understand Americans than they do many of their own countrymen. No one butchers English like the English.

I showed my wife some Canadian bacon in the store a couple of days ago and she said ‘that’s not bacon, what is that?’. And I said ‘exactly’.

I’m fine calling circular rounds of pressed ham luncheon meat “Canadian bacon”. It makes it seem more exotic, like using a dollop of mayonnaise as a dipping sauce for French fries.

I’m patriotic as well as yummy. Hence the magic part of my name. *jumps in frying pan and flies off* (sizzling sounds)

Tremendous article, Eddie. Very enjoyable read.

OT: Roadz!!!!!

Hey guys, we’re famous.

http://franklycurious.com/wp/2017/03/14/glibertarians/

Apparently we are all alt-right now.

CRIPPLE FIGHT!!!

Make it a crippled orphan fight, and you are on.

Crippling orphans is what libertarians do best!

Oh, Dear Lord, not only did I lose three minutes of my life reading that drivel, I’m now slightly dumber for having been exposed to it.

I couldn’t even get past a few paragraphs. The guy obviously does not understand what libertarian means and then he tries to take something he has no understanding of and compare it with something else (the name of a website), resulting in DERP.

Well understanding is hard, attacking strawmen is easy.

It’s come up before. I made a couple of comments there but gave up when the author, who’s totally not a Marxist, couldn’t say anything except “read Marx” and “income inequality”.

Read Marx? LOL.

I did, now it is my emergency toilet paper in case we ever get a socialist in power.

He’s rational to a point, but his arguments break down if you refuse to accept the premise (which Marx requires) that if a thing has “moral” value it must therefore also have economic value.

Didn’t sloopy try to get him to make an appearance here months ago?

You can’t argue with the left because logic is not something they get. They’ll just keep saying stupid things, such the only thing libertarian stands for is more tax cuts for the 1%. How about I don’t care if the 1% gets a tax cut as long as I get one too? No, that simple thing is too complex for them to grasp.

HM gives ’em what-for at the end.

Oh, I have a lot more in store for Francis and company.

‘Alt-right’ has already become as worthless as ‘neocon’ as an indicator anymore because it’s been so broadly used. Two years from now the term will normalized and they’ll move onto something equally dumb.

It’s a beautiful thing, the Destruction of words mr. Titor.

also neoliberal which means bad. And fascist which means not communist.

Neoliberal is especially weird to me because a lot of my educational background was in international relations theory and there neoliberal actually means something, so when I have these shrieking idiots talk about neoliberalism I immediately think “what, they like NGOs?”

What the hell is this whole neo-liberal thing I keep seeing bandied about? I’m assuming it means a formerly Democratic voter who has not drunk the prog kool-aid.

Basically. Neoliberal seems to be an almost all-encompassing term for socialist heretics.

Neoliberalism is what is destroying the dream in Venezuela. Neoliberalism causes the problems in Cuba. Neoliberalism ruined the great economies of eastern Europe.

Neoliberalism as an economic concept was originally a thing that popped up in the 80s, basically a rejection of Keynesian economic principles in favour of a more liberalized economy, so Thatcher, Reagan, etc. It basically became a catch-all term for ‘privatization, ewwwww’ for the left and then expanded to just be ‘things we don’t like’.

If I’m reading between the lines correctly, then is it accurate to say neo-liberals favor a more privatized economy while keeping social safety nets in place?

That sounds so mainstream and centrist it hurts.

In its original form it was related to privatization and free trade agreements (or at least what we call free trade agreements, like NAFTA) but it’s, as Pie notes, morphed into a meaningless term.

Even the wiki page has noted that defining it is basically pointless because the left made it so broad as to be meaningless:

Modern advocates of free market policies avoid the term “neoliberal” and some scholars have described the term as meaning different things to different people, as neoliberalism “mutated” into geopolitically distinct hybrids as it travelled around the world.As such, neoliberalism shares many attributes with other contested concepts, including democracy.

In Naomi Klein’s garbage book The Shock Doctrine, for example, she interchanges neoliberal, neoconservative, libertarian, conservative, etc. constantly.

What annoys me is his description of libertarian philosophy as “faith-based,” which I presume means he denies the empirical underpinnings of many philosophical systems? Or perhaps he just rejects their axioms. Truthfully having read a number of his articles I’m not convinced he’s all that solid on logic.

Which is hilarious, considering the fact that he was a “climate scientist” before becoming a functional heroin addict.

So he doesn’t see the irony of saying that while being a true bleever of an ideology that has failed spectacularly every time it’s ever been tried?

They always say it is not “real socialism”.

Yep.

So that’s what a true prog looks like.

This is what true progs look like.

https://www.reddit.com/r/LateStageCapitalism/comments/6l7u49/happy_4th_of_july/

Wait a minute… 4th of July fireworks are about profit? Huh, I went to fireworks last night and they were free.

If all parties come out of a transaction happy, your average prog isn’t going to like it.

There are no winners in a transaction unless the outcome is decided by the state. /progs

They said Venezuela was real socialism until the part where they ran out of other people’s money. Now we’re back to the search for real socialism. I guess when you never admit it’s real socialism, you get out of admitting you’re wrong.

IT”S STATE CAPITALISM!!!!!!!!

Well, it takes a certain kind of mindset . . .

Also, hook me up with your steam name so we can ruin people in Red Orchestra.

How is that game, I have heard good things.

Have not played that one, but I just got PlayerUnknowns Battlegrounds.

It’s like that movie Battle Royale, but with more people. 100 people dropped on an island, you find weapons and gear and then try not to die. 1 life, last man standing wins.

Dr. Fu Manchu

Awesome. I’m rolling as Josiah Buckshank, or occasionally I think|FOS|J. Buckshank.

The game itself is great, its the perfect blend of arcade and sim. More sim than Battlefield or Day of Defeat but less intensive than ARMA. There is a satisfying amount of effort required to get kills, but you’re never stuck traveling to get them for 30 minutes in a vehicle. Fun and interesting array of weapons, well thought out maps, bullet drop, penetration, etc. Rewards teamwork and individual proficiency. Best fun ever if you’ve got a good squad.

Indeed. Bounding overwatch is the name of the game.

Thanks, now that I have a computer not held togeter by duck tape I will look into it.

Darn autocorrect I meant duct tape.

Its great when you can pull it off, half the servers people run all over. Still, worth it those times when people are actually using squad voice and bother spawning on the leaders. So many fun moments… Binocular kill, the other guy realizing your C96 has an alternative fire mode, satcheling that tank who thought he was safe…

Works either way, my dude.

Duck tape is immoral. I suppose you’re into cat juggling as well?

IIRC its based on the Unreal 3 engine so if you trim the settings it shouldn’t be too hard on your machine.

I am a Libertarian, cruelty is my speciality Hyp. So yes.

I find orphan tossing more rewarding. Also, only juggle declawed cats unless you’re wearing full body armor.

Can you loopzook? If not I don’t care.

No aviation assets in RO2 / RS, only mortars and artillery including rockets and naval fire support. I’d say the game is worth it on the strength of the MG42 alone – it just sounds so mean.

Also, I think I’ll need more than that. To add a friend “Dr. Fu Manchu” returns 366,563 hits. I really hate that they’ve made it impossible to add via email or steamid.

Umm..the one from New Hampshire?

Guess I’ll start looking. Is your avatar the same as the one in the forums or is it something else? Sent a request to the first hit that exactly matched your spelling and punctuation, had a private profile so I guess we’ll see.

No, the avatar is Christopher Lee as Dr. Fu Manchu.

Like this.

Actually probably easier to just give you this profile link and hope you can add me as well. Ought to get a glib gaming group up, seen enough people into it here.

Ok. Done.

Well there’s a lotta nerd talk in this thread

You’re just jealous because you only have working electricity three hours a day and the Ukrainians and Poles make better video games than you.

But on the other hand at least we are not Poles or Ukranians.

I’ll give you the Ukrainians, but I’m with Pan on this one, the Poles are the most noblest, wonderful and majestic of the Eastern Europeans. They proved their worth in killing a lot of The Turk and The Red as well.

What do you guys got, Vlad Tepes and failing horribly in World War I?

Hey John, did you successfully quit cigarettes?

Well we have a Latin language which is better than Slavic so there.

But besides old Vlad, Romanian killed a lot of Turks throughout history. Unlike say the Bulgarians who folded.

It’s been four months, you have no power over me anymore.

So, you’re done with nicotine entirely?

Ah, you may have killed some Turks, but you didn’t ‘largest cavalry charge in human history’ kill Turks. Also Polish freedom oriented history like the Constitution of 1791 makes them come off better in terms of libertarian cred.

Also, there’s that whole ‘siding with the Nazis’ elephant in the room here…

I had a cigar on Canada Day but that doesn’t count.

Ugh, screencaps from Avatar again, John?

I don’t think we would have had much choice in the joining the Nazis thing. But we were kinda lame when we changes sides as the tide was turning

Also the Polish Hussars were a bunch of wimps. With their silly wings and all.

As far as I understand, there was originally neutrality, and then you joined the Axis because Stalin stole some Romanian land, you were a dictatorship, and were partially influenced by the anti-Semitic ‘Iron Guard’ movement. Then the military took over and most of your Jews were shipped off ‘somewhere’ and you didn’t surrender until the Soviets overwhelmed your borders in ’44 (or ’45? Can’t remember).

Well we didn’t just surrender we fought against the Germ,ans in the end

Also the Polish Hussars were a bunch of wimps. With their silly wings and all.

You stand in front of their charge and say that. The wings were said to howl as they rode and scare enemy horses. That’s badass.

From what I researched, they were neutral, then after they lost land to the Soviets because of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact the Iron Guard/pro-Hitler fascists took over, and sided with the Axis. They helped in Barbarossa, then when the Soviets bombed the shit out of them and invaded in 1944, there was another coup and they joined the Allies.

Yeah, because your country was owned by Stalin and he used your population like the Mongols did, frontline troops.

I don’t think we would have had much choice in the joining the Nazis thing.

Well, to be fair, you had a good example next door of what happens when you don’t.

And the “joining” was partly to reclaim Besarabia, and partly to placate Nazis so that they’d stop giving more Romania to Hungary. Basically a bidding war.

Switching sides was totally justified by German response to Soviet Operation Uranus – “oh, you are getting crushed by overwhelming force we never noticed building up? So sorry, mice chewed our wires, we can’t come help. Good luck, we’ll be retreating now!”

invaded in 1944, there was another coup and they joined the Allies.

I believe they actually had rigged elections that put the communists in power, Stalin’s standard M.O. in Eastern Europe.

Also holy shit your monarch is still alive.

That was after the coup though. They basically handed the government over to the Red Army and Stalin got rid of all the pro-Western officials.

What about the Czechs?

Great porn. Maybe best porn. Romanian porn is laame

How’s the Polish porn?

Asking for a friend, obviously.

Well in my experience Czech porn stars are better in the sack then Polish ones.

You have the internet, it is not hard to find (and I agree with Pie, Czech porn is quality porn).

Meh, don’t actually watch it. I like the Czechs mostly because of their pro-gun and fairly pro-business stance.

Seriously. If he’d just be forthright and say, “I deny the NAP as the axiom of libertarian philosophy” then I’m sure he’d probably catch a lot less flack.

Honestly I would like leftist to go out and directly say I am against liberty and believe we should all be serfs of the state. He can then try to justify this belief, but at least it would start honest. But it does not sound good to be against liberty

Partly why I liked having Bernie out on the stage, he was more or less an honest communist so I didn’t have to feel bad about calling him evil and pointing out the moral corruption of all the Berners I ran into.

Some of them genuinely* believe that they are pro-liberty, in the sense of FDR’s Four Freedoms, where “freedom from want” and “freedom from fear” (and other positive liberties) are elevated to the same level as “freedom of speech” and “freedom of speech” (and other negative liberties). The problem is that positive and negative liberty are in conflict. If you are free from want, that means you are always provided for, which requires someone else to provide it no matter what, which means somebody’s freedom has to be restricted in some fashion. The intellectually honest ones will admit to the conflict and reveal that there is some freedom that they consider worth giving up to achieve the others (the problem starts when they want to give up other people’s freedom, too). As to the dishonest ones, well we’ve seen plenty of those.

* = Although lots of masks have been pulled off lately, and at least in the sphere of visible public discourse, the number of genuine believers seems to be dwarfed by liars and knaves

Freedom from want and fear are silly because besides being positive they are highly subjective. Like the stupid right not to be offended.,

Well, most of these people are big fans of democracy* and so the solution to them for subjectivity is consensus. As long as enough people want it, it must be worth having.

* = See previous asterisk

Sometimes I think I should engage these people but I fail to see the point. Everything they say i wrong and they don’t even try to understand counter arguments. They attack people and straw-man and I have never seen logic nor reason. It is sadly all so pointless.

I am particularly amused at how the left is against hierarchy when you get a bureaucratic hierarchy which dictates your life,

And their sad belief that the bureaucracy will be totally controlled by some sort of democratic process against all evidence to the contrary.

Wait, you guys are republicans?

TSTSNBN was right!

Reporter associated with the NYT(*) attacks reality.

(*)she describes herself as a writer for the NYT Sunday Styles desk but her Linkedin profile says freelancer. Bonus- grad degree from Columbia(**)

(**) but in Theater Arts, not Journalism. Undergrad is in Dramatic Writing.

No doubt another victim of leftist brainwashing.

I love one of the responses to her from the previous thread. I think she locked her account so I can’t find the original. It’s to the tune of “Would you prefer the pilot make a 19,000 ft vertical descent to land?”

heh, yep, that was the one I pasted in the morning links. Girl had pilots and controllers showing her exactly how and why she was wrong, and she just kept soldiering on.

She kept claiming that the pilot was clearly drunk. Someone should have told her that bloody marys have alcohol in them.

Here it is:

Jeff @Pilot_Jeff · 20h20 hours ago

You cross NYC at 19,000 feet on arrival. Would a straight vertical dive into JFK be preferable to descending over water and turning back?

The pilot doesn’t even decide the flight path. Once you’re anywhere near New York, you’re in Class B airspace where the tower tells you where to go.

Sorry! Didn’t make it all the way through morning links today.

Did the undergrad dramatic writing degree have a concentration in melodramatic writing?

OMG

http://cdn.pastemagazine.com/www/articles/Screen%20Shot%202017-07-05%20at%2011.38.07%20AM.png

As Swiss once eloquently put it = “Some people mistake taking flak with being over the target”

-1 Ball Bearing Factory

“Some people mistake taking flak with being over the target”

Good one. I missed that.

I know a lot you Glibs are programmers. I don’t know if any of you have much experience with industrial programming. I have been doing more and more of it lately. That said, The Rockwell automation engineers can all go die a fire for the way they make firmware updates on hardware incompatable.

Show me on the doll where the automation engineer touched you.

Right in the PLC I’m guessing

It the way they change firmware on their hardware every few months. I have a Variable frequency drive that the powerpack shorted out after the motor was hit with a crane. I installed the drive less than I year ago. I go to replace it, and bam, it won’t talk to my PLC. I have to go get a different computer and hook a crossover cable directly to the ethernet port on the drive so that I can download retrograde firmware off the interest and flash it to the drive just to get the PLC and drive to talk. Then, when I get some down time in a week or so, I am going to find all the like type drives in the plant and upgrade all their firmware to the latest version and upgrade my PLC firmware to the latest version. Then everything will be good, until 6 months from now when Rockwell puts out another non compatible firmware upgrade. It basically a massive pain in my ass.

Sounds like spreadsheet inventory will be in your future.

Also, just talking out of my ass- maintain local archive of you in-use firmware/software so you’re not reliant on find it somewhere out there, and flash your spares as you receive them (if accessible and not in some tamper proof packaging) so they’re ready to go.

Yeah, I keep a database of what is running what firmware. It not really possible to change the firmware on components that are in storage as they may be used in different parts of the plant and won’t necessarily be running the same firmware.

Jesus. Spreadsheet inventory? You don’t even use Access or a freeware database? Fuck me – that is not what Excel is meant for (note: I know you know this, GL, just… fuck)

No, it’s not. But it’s simple and everyone has it on their PC. Good enough for a small list of units/locations/firmware versions and copies to email in a easy to read format.

Want to hear about using Excel to build copyable scripts from input selections next?

No, because I can/have already do/done that. (At least if you’re talking about SQL).

I wasn’t trying to rag on you, man, just… fuck. This is the kind of shit that blows my mind. How some companies cannot get that a minuscule investment would gain them massive rewards – well, I don’t know . UPC scanners aren’t that costly.

…and it looks like I should have refreshed and/or rethought my post before posting. Ah well, I can handle the shame.

I have experience in mfg programming. I mean like PC to machine interfacing, automated production lines. All of that sort of stuff.

I know what’s going on here, don’t think that I don’t. You fuckers are building Skynet.

No no nooooo nothing like that. It’s called Ultramesh Cybermaster.

Needs a Roman numeral on the end for teh authentici-tay

XL

Building an army of robot slaves and an interstellar starship to GTFO.

I’m doing human machine interfaces, variable frequency drives, and PLCs. It actually pretty fun for the most part. This software revision compatability stuff just is a major pain in the ass.

All this pirate talk is good, but where is the map to the treasure?

In your booty?

As long as we’re bitching about work- I got roped into the end stages of an internal project that quickly became clear it’s not going to go on time. Well clear to myself and one or two close colleagues that are obviously debbie downers too.

The project manager is dedicated to the promised due date, and is beating our buyers & vendor for backordered parts that have a ship date after this due date. Yeah, not going to happen. There’s several other things that haven’t been done as well and doesn’t seem to be any movement there but the PM still seems to think it’s going to happen rather than planning for a reschedule now. Killing time until the next call starts, but really could care less today.

Sound like you may need to explain a certain river in northern Africa.

Most of the times I’ve seen projects not go on time is because of massive scope creep or because the clients keep changing requirements.

I’ve been involved in some where the PMs just didn’t care. Mostly in Europe.

Have never seen that. But I have been involved in a couple where the clients didn’t seem to care, or where they just lost interest and decided they wanted something else instead. That always involved academia being the client.

It’s really something when you sit in on a project meeting when the prototype is due in three days, the materials aren’t there, and nobody has bothered to call the supplier to find out when they’re coming. Oh, and no overtime.

I’ve had clients where you wait forever on requirements and after having spent so much time figuring out what they want, they change their mind halfway through the project. It’s sort of like someone asking for a 2 story building and then after you’ve built it they look at it in a bewildered way and say ‘Wait… who told you to build that? That’s not what I wanted, I don’t want the first floor’.

Other than the vendor delay, it probably can all be swept under scope creep because the initial people involved didn’t understand the scope. Lots of reshuffling lately and people getting thrown into roles they don’t have a lot/any background in. The good news about large organizations is they keep steaming ahead even as the waterline creeps upward.

Andrew Kaczynski puts the tuff into tuffgai

Reason for bringing back dueling #39637.

This guy may have more serious issues than challenging Shapiro to a tough guy contest.

What, like a blackmail charge?

I’m not sure where that lies legally, but it sure sounded like blackmail to me. I mean when you say ‘I’m not going to have your leg broken now, but if you do it again, Guido will be visiting you’. And then you publicly brag about doing it.

I’m wondering if CNN will fire him, at the very least.

It’s possible there’s not enough to have actual charges, IANAL. no real idea either way on that.

I thought that they would have done some form of token gesture by now, maybe issue a lame apology, but doesn’t appear they are worried, yet.

I have no idea who these people are but this link from the feed is great:

https://www.stripes.com/news/europe/soldier-charged-in-humvees-free-fall-1.476690#.WV0_vxg-KHp

Drop zone or impact zone?

https://youtu.be/l-YsSL65quM

What happened to the links?

Robbie has them today.

I smell another riot

A pussy riot?

A pussy riot.

You don’t want to know what was briefly posted in their place….

Jesse did a Thicc Wednesday with men with massive butts?

Worse.

I swear he’s just getting lazy now. Or he’s planning to release a Collector’s Edition.

TW: BuzzFeed

Still, a decent analysis that Trump didn’t post a gif taken from Reddit:

https://www.buzzfeed.com/ryanhatesthis/how-a-random-gif-from-reddit-probably-ended-up-on-president

So basically CNN doxxed and threatened the person who took credit for it, not the person who made it.

Looking fly there Zardoz! Taking wardrobe hints from Gilmore?

WILLIAM PENN DENOUNCES “WHOSE WHO LIVE AND HAVE PLEASURE IN THEIR CURIOUS TRIMS, RICH AND CHANGEABLE APPAREL, NICETY OF DRESS, INVENTION AND IMITATION OF FASHIONS, COSTLY ATTIRE, MINCING GAITS, WANTON LOOKS, ROMANCES, PLAYS, TREATS, BALLS, FEASTS, AND THE LIKE CONVERSATION IN REQUEST: FOR AS THESE HAD NEVER BEEN, IF MAN HAD STAYED AT HOME WITH HIS CREATOR, AND GIVEN THE ENTIRE EXERCISE OF HIS MIND TO THE NOBLE ENDS OF HIS CREATION; SO CERTAIN IT IS, THAT THE USE OF THESE VANITIES IS NOT ONLY A SIGN THAT MEN AND WOMEN ARE YET IGNORANT OF THEIR TRUE REST AND PLEASURE, BUT IT GREATLY OBSTRUCTS AND HINTERS THE RETIREMENT OF THEIR MINDS, AND THEIR SERIOUS ENQUIRY AFTER THOSE THINGS THAT ARE ETERNAL.” – From NO CROSS, NO CROWN: A Discourse showing the Nature and Discipline of the Holy Cross of Christ, and that, the Denial of Self, and Daily Bearing of Christ’s Cross, is the alone Way to the Rest and Kingdom of God. (1682)