I suppose I don’t have to ask if you’re familiar with the phrase “beaten like a red-headed stepchild.” I am going to describe how one of the rights listed in the Bill of Rights – the right to a grand jury – got that treatment at the hands of the states.

Today I’ll discuss the U. S. Supreme Court’s role in all this. It was a case the Supremes decided in 1884. I’m going to focus less on legal analysis and more on biographical details about the defendant and the judges who judged him. If I seem to wander away from the specific case in order to describe the lives of the Justices, I hope it doesn’t bore you, but instead helps demythologize these supposed demigods who purport to adjudicate the limits of our liberties.

And the fact that, given the unpromising backgrounds of these two justices, even one of them (Harlan) was willing to stand up for the Bill of Rights and its red-headed stepchild, the right to a grand jury, is all the more impressive.

The case involved

Joseph Hurtado

…a resident of Sacramento, California who, according to a chronicler of his case, like other “Hispanic men of the era[,] enjoyed nothing better then to cast aside their burdens from a hardscrabble life to frequent pulquerias, or saloons, imbibe prodigious quantities of liquid refreshment, gamble, and hurl epithets at each other” (if the chronicler wasn’t named Martinez, he might get in trouble for that sort of broad generalization).

Saint John of the Cross, a Hispanic man and thus presumably a brawling party animal

Hurtado was the kind of man you can find among all ethnicities – the kind with a violent temper, especially when provoked. He had already killed a man, but had been acquitted.

A friend of Hurtado’s, José Estuardo, somehow decided that it would a wise course of action to have an affair with Hurtado’s wife when Hurtado was at work.

When Hurtado found out, he made Estuardo promise not to do it again – in exchange for this promise, Hurtado let Estuardo live. Then Estuardo broke his promise and went back to banging Hurtato’s wife. Hurtado found out again and attacked Estuardo in the street before getting restrained by passers-by. Estuardo had Hurtado prosecuted for assault – “He is a dangerous man to be at large,” Estuardo warned the court (Estuardo should have thought about that earlier). Hurtado, released anyway, went to a saloon to drink, acted like he was waiting for Estuardo to come by, then he came out and confronted Estuardo, this time shooting Estuardo to death.

This was, to be sure, a case that looked very much like premeditated murder, though a sympathetic grand jury might have stretched a point and filed lesser charges for this crime passionel. But no grand jury considered the case. Invoking a provision in the state constitution, the prosecutor persuaded a magistrate rather than a grand jury to send the case to trial. Hurtado was charged with capital murder, convicted by a trial jury, and sentenced to death. The rules of evidence at the trial (unlike the more flexible rules of a grand jury hearing) didn’t allow evidence of the adultery, thus depriving the crime of its context (which the grand jury might have considered). The judge suggested commuting the death sentence to life imprisonment. A citizens’ committee complained that the jury should have heard about Estuardo’s adulterous ways. And some locals suggested that Estuardo had simply gotten what was coming to him. But the death sentence stood.

Hurtado went to the U. S. Supreme Court with the claim that he shouldn’t have been brought to trial, because a grand jury had not indicted him. Perhaps Hurtado’s supporters hoped that a grand jury would have reflected some of the local pro-Hurtado sentiment.

Hurtado invoked the Fourteenth Amendment, especially its guarantee of “due process of law” (the “privileges and immunities” clause had been watered down to homeopathic levels by earlier Supreme Court decisions). According to Hurtado, “due process of law” included the following guarantee from the Fifth Amendment:

No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a grand jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the militia, when in actual service in time of war or public danger…

This has generally been read to mean roughly that nobody could go on trial for a felony unless a grand jury has first accused him of that felony. And Hurtado’s case involved a “capital…crime,” which was specifically subject to the grand-jury clause. California had not used a grand jury in Hurtado’s case; did the states have to do so, or did this part of the Fifth Amendment apply only to the federal government?

Hurtado’s conviction was OK, said the U. S. Supreme Court, because the Fourteenth Amendment (contrary to what Hurtado claimed), did not require states to obey the Fifth Amendment’s grand jury clause. Only the federal government had to obey it.

The case marked a clash between two of the Justices. Both were Republicans who had worked together even before serving on the Court. Both of them veterans of the Union Army in the Civil War. And both of whom had records leaving their support for civil liberties open to question.

In one corner was the author of the majority opinion,

Justice Stanley Matthews

Stanley Matthews (not the soccer player)

Matthews grew up in Cincinnati, but as a young man before the Civil War, Matthews lived in Tennessee, met his wife there, and helped run a Democratic newspaper. His father worried that Matthews would pick up Southern ways from living in the South.

Matthews moved back to Cincinnati to be a lawyer-politician. He befriended antislavery leaders like Salmon P. Chase and became the editor of the Cincinnati Weekly Herald, and then of the Cincinnati Weekly Globe, which promoted the antislavery Liberty and Free Soil Parties respectively. To Matthews, slavery was now “that awful chain of bondage, which holds three million of immortal souls in hopeless degredation.” Under the Constitution, Matthews wrote, “all men have an indefeasible natural right to freedom.” After all “Who can doubt the essential sin of slavery?”

Matthews considered joining a Fourierist phalanx (socialist commune), and he flirted with the Know-Nothing party, but ultimately he decided to go back to the Democrats. He remained in the Democratic Party even after most antislavery Democrats had left. The Democrats might be pro-slavery, Matthews thought, but the party could at least defuse the slavery issue and preserve the Union from disintegration.

Or as Matthews’ biographer William Wantland put it (in a different context, but the remark is applicable to Matthews’ Democratic Party membership): “Torn between the desire to follow a moral path in the political arena and an equally powerful desire to perpetuate an allegiance with friends and maintain avenues of personal advancement, Matthews generally chose the latter course.”

In 1857, Matthews helped the prominent pro-slavery Democrat Clement Vallandigham defend the pro-slavery position. Federal marshals, attempting to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act, shot a county sheriff who was trying to interfere with this enforcement effort. Matthews, Vallandigham and the rest of the marshals’ defense team helped the marshals escape justice for the shooting.

For supporting the proslavery Democrat James Buchanan for President, Matthews received a reward from a grateful Buchanan: the U. S. Attorney (federal prosecutor) job in southern Ohio. Here Matthews once again engaged in pro-slavery behavior.

William M. Connelly was a Cincinnati journalist who, when not doing his day job, helped fugitive slaves. Two of the slaves he sheltered were Irwin and Angelina Broadus, a husband and wife who were claimed as slaves by a Kentucky Colonel named C. A. Withers. Accompanied by federal marshals, Withers came to a room which Connelly had provided to shelter the fugitives. Irwin Broadus plunged the blade of a sword-cane into the body of one of the marshals, leaving the blade bloody for eight inches (the marshal survived, or else he would have ended up in the U. S. Marshals’ roll of honor). Withers shot and wounded Irwin Broadus. The federal government sent Broadus and his wife back to Kentucky where Irwin Broadus died from his wounds. The Ohio Anti-Slavery Bugle said Broadus had been “Freed at last.”

Meanwhile, Connelly fled to New York, where federal marshals arrested him and took him back to Cincinnati. As the U. S. Attorney, Matthews prosecuted Connelly for sheltering the Broaduses from those who wanted to enslave them. Matthews conducted the prosecution “despite his anti-slavery convictions” (as a law professor later put it).

Thanks to Matthews, Connelly was convicted, but the judge only gave Connelly a 20-day jail sentence and a $10 fine. While Connelly served his sentence, abolitionist women in Cincinnati sent him pastries and other good food. On the day of his release, the jailer was persuaded to keep Connelly locked up for a few extra hours so that a group of supporters would have time to arrive and give Connelly a celebratory parade.

When the Civil War started, Matthews went into the Union Army along with his old college roommate and friend, Rutherford B. Hayes. Matthews had an undistinguished military career, and was not popular with his men. Matthews returned to Tennessee – as part of the occupying army. Due to an injury, he missed out on the important battle of Stones River where many of his men were killed. Soon after that, in early 1863, he quit the Army and became a judge in Cincinnati. He wanted to restore the Union “just as it was” – that is, with slavery still intact; an unrealistic goal as the war progressed. At the same time, Matthews rejected Ohio’s Democratic peaceniks, led by his former co-counsel Clement Vallandigham – these “Copperheads” wanted a truce followed by peace negotiations. Because he rejected any truce, and believed in fighting the war through to victory, Matthews and other “War Democrats” fused with Republicans into the Union Party.

Matthews had joined the Old School Presbyterian Church, the country’s largest Presbyterian denomination, in 1859 – the deaths of several of his children had turned his thoughts in a spiritual direction.

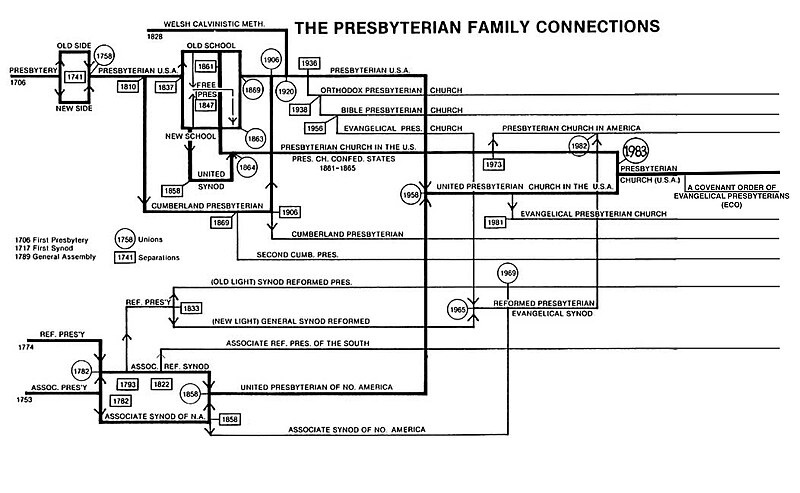

The Old School Presbyterians are not to be confused with other Presbyterian denominations – this simple diagram should clarify things.

The Old School Presbyterians soft-pedaled the slavery issue before the war, to placate Southern members, but after Southern Presbyterians seceded from the church during the war, the now Northern-dominated Old Schoolers took a prowar position. Matthews was a ruling elder of the Cincinnati Presbytery (a subdivision of the church), and as a prominent Presbyterian leader he drew up a report on slavery in 1864 which the General Assembly (governing body of the Old Schoolers) largely adopted during its meeting in Newark, New Jersey. Matthews and his fellow-Old Schoolers had finally accepted that the war was destroying the Peculiar Institution, and Matthews’ report thanked God for “work[ing] out the deliverance of our country from the evil and guilt of slavery.”

Matthews joined the Republican Party and renewed his acquaintance with Samuel Chase, now Chief Justice. Now Matthews was for a reconstruction policy which let the former slaves vote. Supporters of such a policy were then known as Radical Republicans.

Matthews left the Cincinnati judiciary and went back to private practice after the war. In 1869, the Cincinnati School board hired him as lead counsel to defend its new policy banning Bible readings in public schools. There had been hints that the Catholic Church in Cincinnati might want to merge its massive parochial system with the local public schools. The school board realized that the public schools’ practice of classroom readings from the Protestant King James Bible might be a stumbling block to Catholics. So the Board put an end to these and any other Bible readings. Even after the Catholics backed out of the merger talks, the school board continued with its ban.

Matthews felt obliged to resign as a Presbyterian elder, due to the opposition his anti-Bible-reading stance provoked. He warned the court against “Protestant supremacy” – because if the public schools set religious exercises the Protestant majority would decide what those exercises would be. The Ohio Supreme Court ultimately sided with Matthews and the school board. (For more about the “Cincinnati Bible Wars,” click here).

Matthews at first joined the Liberal Republican movement against President Grant in 1872, deploring administration corruption and calling for more conciliatory treatment of the white South. Then Matthews backtracked and endorsed Grant. When he mentioned corruption, said Matthews, he wasn’t talking specifically about the Grant administration, just about, you know, corruption in society and stuff.

Representing powerful railroad interests, Matthews was able to “swell my income” – as Matthews put it to Hayes. He went back into politics when his old friend Hayes was nominated for President in 1876 – Matthews himself ran for U. S. House. Matthews lost his race, but as part of Hayes’ legal team he fought to have Hayes recognized as the victor in the disputed Presidential election. The famous Wormley House Conference was held in Matthews’ room at the Wormley House hotel in Washington – at this conference Hayes’ representatives (including Matthews) agreed to abandon the “carpetbag” Republican governments in the South and the Southern Democrats agreed to recognize Hayes as President and respect black rights.

“Well, that last part is a relief. For a moment there we were worried we were getting double-crossed.”

Serving a two-year term as U. S. Senator from Ohio, Matthews spoke up for an old client of his, railway magnate Jay Gould. He also spoke up for Chinese immigrants and against the gold standard and the New York customs boss, Chester Arthur. Then he stepped aside to let James Garfield take his Senate seat – a seat Garfield had wanted two years earlier.

Garfield was elevated from the Senate to the Presidency in the 1880 election, but before Garfield was inaugurated, the lame-duck Hayes nominated Matthews to the U. S. Supreme Court. Matthews’ Senatorial opponents bottled up the nomination in committee until Garfield took office. Garfield renominated Matthews. The scandals of Matthews’ past life came back to haunt him. Problems included Matthews’ support for railroad interests (his support of Chinese immigration was put down to this), the enmity of New York Senator Roscoe Conkling (Chester Arthur’s sponsor), and Matthews’ enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act. The New York Times called Matthews a “Northern slave-hound and dough-face.”

The Senate Judiciary Committee recommended against Matthews’ nomination. There was a dissenting vote in Matthews’ favor, but that vote came from Senator Lucius Quintus Cincinnatus Lamar, Democrat of Mississippi. Not exactly a resounding refutation of the “doughface” charge.

The Senate confirmed Matthews by a 24-23 vote. Here is a Thomas Nast cartoon on the subject.

So, back to the Hurtado case – Matthews’ opinion said that “due process” did not require grand juries, even for the most serious crimes. Giving such an interpretation of due process

would be to deny every quality of the law but its age, and to render it incapable of progress or improvement. It would be to stamp upon our jurisprudence the unchangeableness attributed to the laws of the Medes and Persians….The Constitution of the United States…was made for an undefined and expanding future, and for a people gathered and to be gathered from many nations and of may tongues….as it was the characteristic principle of the common law to draw its inspiration from every fountain of justice, we are not to assume that the sources of its supply have been exhausted. On the contrary, we should expect that the new and various experiences of our own situation and system will mould and shape it into new and not less useful forms….Restraints that could be fastened upon executive authority with precision and detail might prove obstructive and injurious when imposed on the just and necessary discretion of legislative power…

Facing off against Justice Matthews was the author of the dissent in the Hurtado case,

Justice John Marshall Harlan

Harlan, an Old School Presbyterian like Matthews, had been a Kentucky politician before the war – first a Whig, then a Know-Nothing, then a member of the “Opposition party” (anti-Democrat). He run for Congress in 1858, accusing his Democratic opponent of not being proslavery enough. Harlan in turn had to fight off slanderous reports that he had given legal representation to a slave who had sued for freedom. Harlan lost the race by 67 votes. He suspected the Democrats had committed fraud.

During the Civil War, Harlan became a colonel in the Union army, where he fought against the Confederate cavalry raider John Hunt Morgan.

Part of a John Hunt Morgan statue in Lexington, KY. This is a close-up of the testicles of Morgan’s mare, Black Bess

Laying aside his prewar Know-Nothing affiliation, Harlan praised the courage of the Catholic soldiers under his command.

Unlike Matthews, Harlan was admired and respected by his men. Like Matthews, Harlan resigned from the Army in 1863 – in Harlan’s case because his father’s death required him to provide for his family.

Harlan was elected Kentucky attorney general on the Union Party ticket. He wanted to beat the Confederacy, but he opposed the efforts of Lincoln and other Republicans to free the slaves. Campaigning against Lincoln’s re-election in 1864, Harlan said Lincoln was “warring chiefly for the freedom of the African race,” when he should have simply been fighting to restore the Union. In another campaign speech, Harlan used a joke to illustrate his argument that Republicans had too much concern about “ze little black nigger.” Harlan tried to prosecute the federal commander in Kentucky for freeing slaves.

Harlan opposed the Thirteenth Amendment, and opposed civil rights for black people after the war.

Then in 1868, Harlan saw the light and the scales fell from his eyes.

Or at least he realized that he had a better future in the Republican Party

…and he switched to supporting the Republicans and the Republican-sponsored Reconstruction Amendments, including the 14th.

“Let it be said that I am right rather than consistent,” Harlan told the public.

Harlan worked with other Republicans, including the black entrepreneur and politician Robert Harlan who was probably John’s half-brother.

A more influential connection was Benjamin Bristow, who was John Harlan’s law partner and later acquired fame as an honest member of President Ulysses Grant’s Cabinet. Unfortunately for his reputation among libertarians, Bristow was Secretary of the Treasury and zealously enforced the federal whiskey tax.

Like Matthews, Harlan loyally supported the Old School Presbyterian Church – fighting in the Supreme Court, and winning, in order to keep some church property out of the hands of pro-Confederate Presbyterians. This was an important precedent by which the secular courts deferred to rulings by church bodies.

When Rutherford B. Hayes obtained the Presidency in 1877, he put Harlan on a commission to investigate the turbulent political situation in Louisiana. Harlan and the other commissioners gave Hayes cover for getting federal troops out of the state and letting the Democrats take over. Harlan thought the Democrats had become more enlightened on racial matters – though by the time of the Plessy decision Harlan would have changed his mind.

Later in 1877, Hayes nominated Harlan for the U. S. Supreme Court. Like Matthews, Harlan faced difficulty getting confirmed to the Supreme Court by the Senate on account of his political past. Former Attorney General James Speed reassured hesitant Senators that Harlan “never was a Democrat” and that he had “sloughed his old pro-slavery skin.” Harlan was duly confirmed.

Harlan’s dissent in the Hurtado case said:

Those who had been driven from the mother country by oppression and persecution brought with them, as their inheritance, which no government could rightfully impair or destroy, certain guaranties of the rights of life and liberty, and property which had long been deemed fundamental in Anglo-Saxon institutions….It is difficult…to perceive anything in the system of prosecuting human beings for their lives by information which suggests that the State which adopts it has entered upon an era of progress and improvement in the law of criminal procedure….Does not the fact that the people of the original States required an amendment of the national Constitution, securing exemption from prosecution, for a capital [or “infamous”] offence, except upon the indictment or presentment of a grand jury, prove that, in their judgment, such an exemption was essential to protection against accusation and unfounded prosecution, and, therefore, was a fundamental principle in liberty and justice?

Before leaving Justice Harlan, I should note that he famously voiced a lone dissent against Jim Crow segregation laws, unsuccessfully tried to apply the entire Bill of Rights to the states, and although he didn’t believe businesses had the right to select their own customers, he at least believed employers could choose their own employees.

Epilogue

The Supremes gave their decision against Joseph Hurtado on March 3, 1884. Exactly a month later, on April 3, Hurtado died of “consumption” (probably tuberculosis) in prison. There hadn’t even been time to set a new execution date. The Sacramento Daily Record-Union published a sympathetic death notice, saying that Hurtado “spent the greater proportion of his life in this city, where he had many warm friends.” He had “experienced religion,” and his final moments were spent in the company of his family (including his wife), and of priests and nuns.

Hurtado’s body ended up in the same Catholic cemetery as Joe DiMaggio, in Colma, San Mateo County, California. As Wikipedia explains: “With most of Colma’s land dedicated to cemeteries, the population of the dead outnumbers the living by over a thousand to one. This has led to Colma’s being called ‘the City of the Silent’ and has given rise to a humorous motto, now recorded on the city’s website: ‘It’s great to be alive in Colma.'” More about Colma here – more about Holy Cross Catholic Cemetery here – consider taking one of the cemetery’s walking tours, but if I had to guess I’d imagine that you’re more likely to be shown the grave of Joseph DiMaggio than that of Joseph Hurtado.

“The boast of heraldry, the pomp of power, / And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave, / Awaits alike the inevitable hour. / The paths of glory lead but to the grave.” – Thomas Gray, “Elegy written in a country churchyard.”

Works Consulted

Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution 1863-1877. New York: Harper and Row, 1989.

The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims. New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1861.

Larry Gara, The Liberty Line: The Legend of the Underground Railroad. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1996.

“Local Intelligence,” Sacramento Daily Record-Union, April 4, 1884, p. 3, column 1. Available online at http://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82014381/1884-04-04/ed-1/seq-3/

Clare V. McKanna, Jr., Race and Homicide in Nineteenth Century California. Reno: University of Nevada Press, 2002.

J. Michael Martinez, “Hurtado v. California (1884) and 19th-century criminal procedure,” in The Greatest Criminal Cases: Changing the Course of American Law. Santa Barbara: Praeger, 2014, pp. 1-12.

Stephen Middleton, The Black Laws: Race and the Legal Process in Early Ohio. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2005.

The Record of Hon. C. L. Vallandigham on Abolition, the Union and the Civil War. Columbus, Ohio: J. Walter & Co., 1863.

“Stanley Matthews,” The Sun (New York, NY), May 13, 1881, p. 2, column 6.

Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Ordeal of the Reunion: A New History of Reconstruction. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2014.

Suja A. Thomas, The Missing American Jury: Restoring the Fundamental Constitutional Role of the Criminal, Civil, and Grand Juries. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2016.

___________, Nonincorporation: The Bill of Rights after McDonald v. Chicago, Notre Dame Law Review, Vol. 88, 2012.

Lewis G. Vander Velde, The Presbyterian Churches and the Federal Union 1861-1869. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1932.

William Robert Wantland, Jurist and Advocate: The Political Career of Stanley Matthews, 1840-1889. Ph.D. Dissertation, Miami University, Ohio, 1994.

Jennifer L. Weber, Copperheads: The Rise and Fall of Lincoln’s Opponents in the North. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Tinsley E. Yarbrough, Judicial Enigma: The First Justice Harlan. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Richard D. Younger, The people’s panel: the Grand Jury in the United States, 1634-1941. Providence, RI: American History Research Center, Brown University Press, 1963.

Matthews switched positions more times then Hillary.

Good article. I’m enjoying these looks into past Supreme Court cases and the Constitution.

Angelina, the slave wife? Would.

That’s all.

Are you talking about the painting? Yeah, she’s very attractive.

I imagine by now her looks have gone.

Which just proves that, in addition to being a sexist mysoginist, you’re also a liveist and a not-decayedoginist!

Just to be clear – and feel free to click my images, that usually gives you the source – this was a painting by Richard Ansdell from 1861 entitled The Hunted Slaves. I don’t think Ansdell actually ever met the Broaduses.

…still would.

*applause*

Great article!

What the hell did he think was going to happen?

His big head knew, his little head didn’t care.

I was actually thinking of Hurtado.

H: “Hey, don’t sleep with my wife!”

E: “Ok, boss!”

Yeah, Hurtado was an idiot. How easy would it have been to get away with murder back in those days? Don’t even let on that you know. Just make Estuarto disappear. Then go find a new woman who isn’t a whore and get on with your life. Not that it mattered much in his case since he was going to die soon anyways.

Nice article. Thanks. After all that the dude dies a month later.

So, he would’ve been OK with forced gay Nazi wedding cakes?

They completely glossed over the perv factor.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/music/articles/84fd62c3-f5a4-49e6-9e3e-6f5217c1448c

Well, I can confirm that “Baby Driver” continues Edgar Wright’s streak of high quality auteur flicks. In particular, the sound editing and mixing is extremely well done – even choreographing shootouts directly with certain tunes. Highly recommended.

(looks dude up)

huh, i always thought those films (his ‘trilogy’) were actually creations of Pegg/Frost

i’ve never seen ant man. worth it?

It’s OK, but Wright got fired from it, so not representative.

Yeah, it’s still good, but the tone/style definitely would have been different with him directing. Edgar Wright/Pegg/Frost all collaborated on the Cornetto Trilogy – but they started out before that with the *amazing* “Spaced” Tv show – highly recommended – may be on netflix.

Correct.

Ant-Man is pretty decent, just remember to forget everything you ever knew about physics before you start watching.

It’s meh. Pretty disposable. I think it would’ve been a more interesting movie if they’d made it more about Evangeline Lily’s character and not Paul Rudd’s. He’s kind of a bland nobody, in a very familiar origin story.

Wasp is probably my favorite Marvel hero, and definitely favorite Avenger, so I’d be down (yes, I know it’s her daughter. Zero Fucks!)

I liked Ant Man. Corny of course, but it was fun

BTW keep an eye open for all the musician stunt casting – including Paul “Old Fashioned Lovesong” Williams. Pretty cool.

Awesome article, but god damn, what did stick in my mind?

It’s hopeless, Eddie. As an apology, please accept this offering of papal metal.

It wasn’t technically relevant, but looking for an image related to Morgan, I found this close-up of the statue, focusing on the horse’s behind, so I looked it up. It seems the Italian sculptor who made the statue thought a great cavalry commanded like Morgan should have ridden a stallion, not a mare, so he gave the horse a dick and balls.

From the link I provided, there’s this:

“James Loewen, in his book Lies Across America, wrote about the quaint tradition among [University of Kentucky] frat-boys to paint Black Bess’ testicles blue and white, and relayed an old, clunkily-written anonymous poem passed along as local folklore:

“So darkness comes to Bluegrass men —

Like darkness o’er them falls —

For well we know gentlemen should show

Respect for a lady’s balls.”

Gotta love ESPN. In addition to their usual shitty picture, today we are treated to extra crawls – so many that they shrunk the picture left and right too.

Update on the John Hunt Morgan statue

“MAY 26, 2017 4:47 PM

“New Orleans removed its Confederate monuments. What will Lexington do?

“The fate of two controversial Confederate-era monuments on the lawn of the former Fayette County Courthouse is still up in the air nearly 18 months after an arts review board recommended the statues of John C. Breckinridge and John Hunt Morgan be moved….

“The debate on whether to remove the statues started after John Hunt Morgan’s statue was vandalized in June 2015 with black paint that read “Black Lives Matter.” After the incident, [Mayor Jim] Gray asked the Urban County Arts Review Board, which reviews public memorials and art, to make recommendations on whether the two statues represented “the shared values” of Lexington….

“The Urban County Arts Review Board spent four months studying the issue before making its decision in November 2015. It heard from more than 308 people either through email, letters, public forums or phone calls. In addition, it consulted experts in history, architecture and civil rights….

“If the city moves the statues [of Morgan and John C. Breckenridge], it must get permission from another state board that oversees military statues. That board only meets twice a year and its next meeting is in November. If the city decides to move the statues, it likely won’t have its application in until November, Hamilton said. In that application, it must designate where the statues will be moved.

“In addition, the Lexington Urban County Council must also approve moving the statues.”

Old Soviet Joke: “We dont worry about the future. We know the future. It’s the past that is always changing.”

I cant wait for our grey, drab, soul-crushingly dull, poverty ridden, crime infested socialist utopia. I remember an east german describing life in such a paradise. Since no one ever knew what was allowed to be said or who might inform on them, including family members, no one spoke in the street and very few words were said even at home. He said it was a silent country, silenced by fear.

Have they hanged Merkel yet?

Geez, they’re not quite at East Germany levels of hellhole yet.

Odds on public executions under sharia courts in the next ten years?

For what the ruling class have done to their own country, they should hang.

Zero.

OK, here’s an idea…relocate the Morgan statue to the Pewee Valley Confederate Cemetery. There used to be a Confederate soldiers’ home, but now the residents have transferred to the cemetery. Many of the people buried there served under Morgan.

It’s only about 70 miles from Lexington to the cemetery as the crow flies. so if you get a big enough crow (or failing that, a big enough truck), you should be able to transfer the statue to watch over Morgan’s veterans. And the college students will have to drive further in order to paint the mare’s balls.

Driving 70 miles is nothing for college boys with blue balls on the brain.

About a decade ago, the Estonians tried to do this with a statue of a Red Army soldier in Tallinn. The neo-Soviets responded with a DDoS attack on the entire .ee domain.

In one of my “I’m totally not conspiratorial, BUT…..”-moments, i had this thought =

– re: Otto Warm-beer’s non-autopsy – my instant reaction to that news was, ‘someone from the govt came to them and said, “we know what it is, don’t do an autopsy – we don’t want this to become a public-debate”

i have no evidence of this, and it actually contradicts some of the apparent saber-rattling that’s been done by the Admin. But its just my feeling. Maybe it was something the chinese suggested. What nobody wants is “hard evidence” that the Norks basically murdered an american. Yes, the US and China will still use this as an opportunity to put heat on the Norks, and Trump will pretend he’s avenging our citizens with public statements and PR about various efforts.. but in the end, they don’t want history holding them accountable.

You’d be crazy not to have that immediate reaction. I sure did.

This is what passes for conspiratorial these days?

Art Bell would be ashamed of you people.

Since we’re well into OT time, The Spectator hops onto “Harry Potter and politics” bandwagon. Being

a) UK-based

b) literate (longest-running magazine in English language)

c) squish-Tory (despite which political diversity among its contributors puts every other magazine I’ve read to shame)

the analysis is much better than any I’ve seen.

Interesting – I too wondered at the fascination with ‘boarding-school’ life.

I found the Orwell essay on the subject mentioned in the article. Among other things

The more things change etc…

BTW, probably nobody remembers but I was looking for a good Glib-themed license plate a few months ago. Registration came up and I took advantage of the opportunity to go ahead and get a VA Gadsden plate with “NAP FTW” – the best thing I could think of with the character limit. Turned out pretty well and I’ve got it for the next 3 years.

“Yeah, Officer, I think the plate said something like FAP NTW.”

Or “FYTW” …

You want people to sleep in short bursts.

Many years ago my aunt mentioned seeing a vanity plate that had the letters JSS LVS, to which I immediately responded, “Jeez, Elvis!”

Yeah, could be misconstrued, but it’s safer than FYTW.

Peek inside the luxury hotel on wheels

How long until the TSA sets up checkpoints in the bus stations?

No. I will drive myself, thank you.

Another teacher up to extracurricular activities

http://www.foxnews.com/us/2017/06/30/married-health-teacher-29-accused-having-sex-multiple-times-with-her-17-year-old-boy-student.html

Truer words have never been spoken

Quick thinking kid

http://www.foxnews.com/us/2017/07/01/alaska-boy-11-shoots-bear-charging-fishing-party.html

It’s there some organized effort going on to ship the entire 3rd World to the West? I’m not understanding what is going on here? Am I missing something?

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-40470102

I don’t think so. More, it’s a collapse of various African countries and the migrants’ recognition that Europe lacks the will – for now – to put a stop to the influx.

*shrug*

Col Gaddafi’s legacy continues. He was the first one to send thousands of migrants in, noticed that EU has no intention of turning them back, then threatened to keep sending them unless protection money is paid (it was). Now they have no one to outsource their border enforcement to, and they aren’t willing to do it themselves.

PM Zoolander lives up to his nickname, again

See now if he tweeted outrageous nonsense every day, nobody would pay attention to something so trivial.

Rhywin, we have to keep him on his toes. If he can’t teleprompter, how can he be Canadian Obama?

Good Heavens, what a cunty thing to do. On Canada’s Birthday, no less. I’d like to grab that asshole by the scruff and grind his nose into the carpet every time he “makes a mistake”! I watched his boxing match, I’d murdalize him.

All 57 provinces, amirite?

*Wanders away from Saturday morning links to assist in family emergency*

*Five hours later, returns, checks comment count*

Holy shit, 500+ comments

*Scrolls up page to HM/Fusionist exchange on behavior of female classical musicians.*

Turns to second Saturday posting.

The only thing it lacked was John telling HM why he’s an imbecile.

He’s not, but he seems to inhabit a Manichaean universe where you either post links to loud orgasm videos…or you’re a Deobandi Muslim.

You make it sound like loud orgasm videos are bad …

Sometimes HM links are the highlight of a thread but he does have a whiff of SJW that you need to waft away. Being Mulatto and all.

Fair enough, but the opposite of “orgasm video” isn’t “restored Caliphate.”

For example, I suspect that many Amish aren’t in favor of either. And, I will be so bold to say, plenty of non-Amish.